From Carmen Miranda to the Grateful Dead

Brazil and the United States’ Musical Dialogue

Pixinguinha playing live in his 60s, long after switching from flute to saxophone. Photo courtesy of Coleção Pixinguinha

In the 21st century, fans of popular music expect, or even demand, that all styles of music be in communication with each other. Sound scavengers like the American DJ Diplo have made their reputations by going into the favelas of Rio de Janeiro and coming back home with beats and riffs that can be recycled into hit songs by Madonna, Shakira, Beyoncé, Justin Bieber, Usher, M.I.A. and the like. But at the same time, the favela funk style that powers dance parties in Rio is itself a mash-up of influences that include the Miami bass sound, New York Latin freestyle, rap and Kraftwerk electronica.

It is tempting to think of this as a purely modern phenomenon, an aspect of the process of globalization that we see around us daily. But it is not. The reality is that U.S. and Brazilian popular music have been engaged in an ongoing dialogue dating back to at least the mid-19th century, and that such exchanges, both visible and subterranean, have only intensified with the passage of time.

Acknowledging this is crucial to any appreciation of popular music, for the United States and Brazil are the world’s two most influential sources of contemporary pop music. Or as the Brazilian composer and pianist Antônio Carlos Jobim, one of the founders of the bossa nova, was fond of saying, “the only music that really swings is that of the United States, Brazil and Cuba, all places where the black thing and the white thing mixed. The rest, with due respect to the Austrians, is all waltzes.”

The theory of a mutually reinforcing musical conversation between Brazil and the United States is one that has appealed to me since the 1970s, when I first heard the music of the 19th century American classical composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk, a Louisiana native. I was living in Rio at the time, and in a piece like Gottschalk’s “Bamboula,” a fantasy for piano, I thought I detected affinities with chorinho, a Brazilian popular music style that originated in Rio in the second half of that century and remains popular there.

A little bit of research yielded these suggestive clues: because of a scandal—he appears to have behaved “inappropriately” with one of his underage female piano students—Gottschalk had to leave the United States. He chose to settle in Rio de Janeiro, where he died at the age of 40 in 1869. In Rio, he took on additional students, two of whom went on to teach Ernesto Nazareth, the father of the chorinho, and Heitor Villa-Lobos, the celebrated Brazilian classical music composer who began his career playing chorinho in clubs and theaters showing silent movies.

This Gottschalk-chorinho connection dovetails nicely with a cultural theory that has predominated in Brazil since it was first enunciated in the late 1920s, that of “cultural cannibalism.” As Brazilians see it, theirs is a culture that swallows foreign influences whole, digests them, and then spits them out as something new and quintessentially Brazilian. No matter whether the culture so consumed is Gottschalk’s “Creole Eyes” or Afrika Bambaata’s “Planet Rock”—what matters is the transformed, cannibalized product, which can range from chorinho to favela funk.

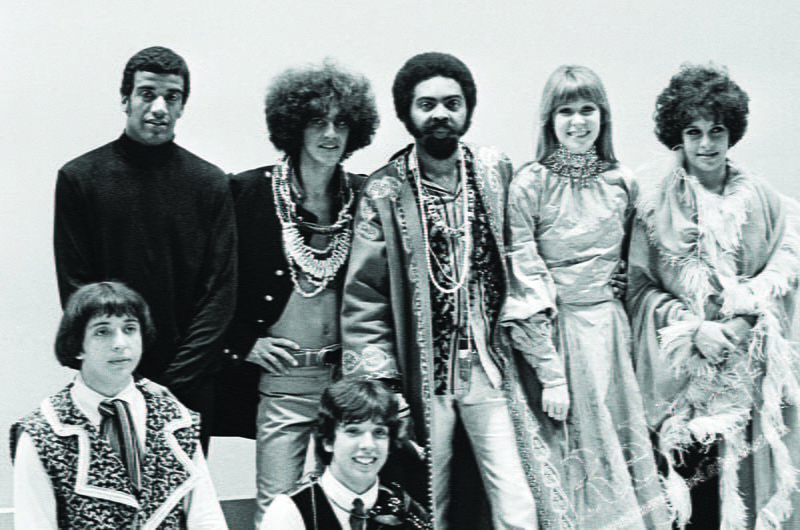

The Tropicalistas, and some of their friends, in 1968, including Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, standing second and third from left.

This early example of Brazilian absorption of a cultural artifact from the United States, indirect though it may be, seems almost a miracle, coming as it did in an era in which music could be transmitted only by live performance or sheet music. But with Edison’s invention of the phonograph in the late 19th century, followed by the popularization of shellac discs early in the 20th century, the dialogue between Brazil and the United States quickened. For the first time, it was possible for a listener a continent away to actually hear a performance, with all of its melodic nuances and rhythmic variances from a written score, instead of having to deduce from sheet music what a song was supposed to sound like.

Late in 1916, an ensemble that included the flute player and arranger Alfredo da Rocha Vianna went into a studio in Rio de Janeiro to record “Pelo Telefone,” which, although permeated with a chorinho feel, is now regarded as the first samba ever to be recorded. Vianna was only 19 at the time, but, under the stage name Pixinguinha, he would go on to become a central figure in the emergence of Brazilian popular music in the 20th century—as revered and important in Brazil as Louis Armstrong is in the United States.

Pixinguinha and his group Os Oito Batutas would record “Sofres Porque Queres” and a number of other songs for the Odeon label, predecessor to today’s EMI conglomerate. These caused a commotion in Europe, and in 1922, the group embarked for Paris, where it held a six-month residency at a club on a street where other nightspots featured American ensembles playing the latest sensation from the United States—jazz. Musicians being musicians, the Brazilians and Americans played together in afterhours jam sessions and sat in on each other’s shows, swapping licks and learning each other’s styles.

On his return to Brazil, Pixinguinha shifted to the saxophone, even then an instrument much favored by jazz musicians, as his main instrument, and changed the make-up of his groups so that they more closely resembled a jazz band. That led to complaints in the Brazilian press that he had “come back Americanized”—an accusation that, up through our own times, has dogged every Brazilian musician who is open to, or experiments in, any foreign style.

Pixinguinha, father of modern Brazilian music, with bossa nova lyricist Vinicius de Moraes. Photo courtesy of Acervo VM

Until the 1920s, U.S. music was more influential in Brazil than vice versa. But that would change in the 1930s and into the 1940s with the emergence of Carmen Miranda. Not only was Miranda a huge movie star—she was the top actress at the Hollywood box office for several years in the 40s—but the songs she sang, first on Broadway, then in her nightclub act and finally in movies, ignited a samba craze in the United States. Even today, songs like “South American Way” and “Tico Tico” remain in the repertoire of dance bands, not to mention that of most every drag queen and female impersonator ever to take the stage.

In a 1940 song called “They Say I Came Back Americanized,” Miranda satirized the usual complaints about changes in her evolving style. But the accusation stung, and she and her band moved permanently to the United States, where she remained until her death in August 1955. Members of her band found their way into American jazz ensembles, bringing a Brazilian flavor.

Yet even as Miranda was being laid to rest in Rio, a new musical movement was germinating in the bars and cabarets of Copacabana and Ipanema. From 60 years’ distance, bossa nova seems like a thoroughly Brazilian style, a quieter and more harmonically sophisticated refinement of samba. But from the beginning, Antônio Carlos Jobim and the other musicians who forged the bossa nova sound—João Gilberto, Johnny Alf and João Donato among them—always acknowledged that they had also absorbed foreign influences, from Chopin’s “Nocturnes” to U.S. jazz icons like Nat King Cole, Miles Davis’s “Birth of the Cool” album, Frank Sinatra and Stan Kenton.

The impact of Kenton, a pianist who led a big band, was especially powerful. His orchestra included Laurindo Almeida, a Brazilian guitar virtuoso who had written hit songs for the Andrews Sisters and others, and the Kenton group had also recorded Brazilian songs like “Delicado” and “Tico Tico” thereby pointing a way to transform Brazilian popular music.

By 1961, of course, bossa nova was being exported all over the world. “The Girl from Ipanema,” which Jobim had written with Vinicius de Moraes, was everywhere: Stan Getz had the hit single in a version he recorded with João Gilberto and Gilberto’s then-wife Astrud, but Frank Sinatra also did a version, which led to him collaborating with Jobim on two albums of Brazilian music. Other jazz musicians, from Cannonball Adderley to Charlie Byrd, also experimented with the style, and even those who didn’t often incorporated bossa nova’s understated drumming style and subtle rhythms into their arsenals.

By the 1970s, most leading-edge jazz groups had a Brazilian drummer or percussionist, starting with Weather Report and Return to Forever, as did the jazz-rock band Chicago. In his most experimental phase, Miles Davis had two Brazilians in his band, the saxophonist and pianist Hermeto Pascoal and the percussionist Airto Moreira, who would later also play with Santana and The Grateful Dead. Brazilian rhythms, as well as cover versions of Brazilian songs by instrumentalists like Wayne Shorter and George Duke, were everywhere in jazz, a situation that continues to this day.

At the same time, though, Brazil was beginning to hear rock’ n’ roll and incorporate that sound into the mix. Roberto Carlos, best known today as a singer of romantic ballads, began as an Elvis Presley and Little Richard acolyte, and had early hits with cover versions of songs like “Splish Splash” and “Unchain My Heart.” And as the 1960s progressed, the emergence of acts like The Beatles, The Jimi Hendrix Experience and the musicians of the San Francisco underground scene only deepened Brazil’s fascination.

The Brazilian response was Tropicalismo, which ingested Anglo-American rock ‘n’ roll and created a revolutionary new style. Artists like Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, Tom Zé and the band Os Mutantes shocked Brazilian traditionalists, including the military government then in power, with everything they did: they played electric instruments, a no-no at the time, and wrote songs with unusual time signatures and veered stylistically from one measure to the next, often mixing American, Brazilian, African and even French chanson influences into one heady stew. Their album “Tropicália: Ou Panis et Circenses” came out in 1968, and was as much a bombshell to Brazilians as “Sgt. Pepper’s” was to Americans.

But during a political crackdown late in 1968, Gil and Veloso were among those jailed. When they were released early the next year, they quickly went into exile—not elsewhere in Latin America, as so many Brazilian political activists were doing—but to London, where they could be exposed to the latest trends in pop music, including music drifting across the ocean from the United States. Married to sisters at that time, they settled into an apartment in Earl’s Court together, and started going to shows: Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, the Isle of Wight Festival, the burgeoning reggae scene.

“England is where I learned to be a showman,” Gil once said to me, explaining that before going into exile he had been more of a static performer, often content to sit as he sang and played his guitar. For his part, Veloso recorded an album known as “London, London,” with most songs in English and splashes of West Indian melodies and rhythms in the music—cultural cannibalism based on whatever material was at hand.

Artists remaining in Brazil such as guitarist and singer Raul Seixas (with the future novelist Paulo Coelho writing his lyrics) followed the same approach: Gilberto Gil once wrote a song called “Chuckberry Fields Forever” but it was Seixas who adhered most closely to a classic rock style. Milton Nascimento, with a voice so sweet that it would lead to collaborations with Wayne Shorter and Pat Metheny, wrote a song called “For Lennon and McCartney,” recorded an idiosyncratic version of “Norwegian Wood,” and in return had some of his songs recorded by Earth, Wind & Fire. Meanwhile, Tim Maia, who had spent part of the 1960s in the United States in rhythm and blues bands, was mining American soul and helping create the “Black Rio” movement that would eventually morph into today’s favela funk scene.

And as the catchall genre known as “world music” began to grow in popularity in the United States during the 1980s, Brazilian music became, along with that of South Africa, one of its principal references. It became chic for rock and pop stars to go to Brazil in search of new rhythms and melodies: Paul Simon, David Byrne, Peter Gabriel, Sting, Michael Jackson and Rod Stewart were among those who made the trek, and Brazilian influences can be heard on songs ranging from “The Obvious Child” to “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy?”

By the 1990s, crate-digging pop musicians and DJs in the United States and United Kingdom had belatedly discovered Tropicália, finding its cut-and-paste aesthetic to be very congenial to their own inclinations. The indie musician Beck was especially enamored: he made liberal use of the Tropicalistas’ collage technique, and even recorded a CD called “Mutations,” meant as a tribute to Os Mutantes.

‘’Hearing Os Mutantes for the first time was one of those revelatory moments you live for as a musician, when you find something that you have been wanting to hear for years but never thought existed,’’ he told me in 2001. ‘’I made records like ‘Odelay’ because there was a certain sound and sensibility that I wanted to achieve, and it was eerie to find that they had already done it 30 years ago, in a totally shocking but beautiful and satisfying way.’’

With the emergence of the Internet two decades ago, combined with a 20-year spurt of economic growth in Brazil that now seems to have hit a wall, yet another stage has been reached. Bands like U2 and Metallica play regularly in Brazil, the singer/songwriter Seu Jorge can record a CD of David Bowie covers in Portuguese and have a worldwide hit, and a Brazilian like Mario Caldato can produce albums by the Beastie Boys or Jack Johnson, and nobody blinks. In the words of Gilberto Gil—who served as Brazil’s Minister of Culture from 2003 to 2008, a sign of yet another profound change—today we live in “uma geleia geral,” an age of “generalized jelly” in which everything is mixed and anything goes.

Winter 2016, Volume XV, Number 2

Larry Rohter spent 14 years in Brazil as a correspondent for The New York Times and Newsweek and is the author of Brazil on the Rise. He is now a fellow at the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers, where he is writing a biography of the Brazilian explorer and statesman Candido Mariano da Silva Rondon.

Related Articles

When Music Changes Lives

English + Español

n 2004, I got a surprising phone call from Santo Domingo on one cold winter night. I was then studying musical composition in Strasbourg, France, a great opportunity for a young Dominican…

The Politics of Gay Marriage in Latin America

Despite its recent successes, the gay rights movement in Latin America is generally ignored in discussions of contemporary Latin American politics. Even students of Latin American social…

The Yaquis and the Empire

Winner of the 2015 Latin American Studies Association Social Science Book Award and runner-up for the 2015 David J. Weber-Clements Prize of the Western History Association, The Yaquis…