About the Author

Thomas “Buddy” Bardenwerper is in his last year of Harvard’s joint-JD/MPP program, thanks to the GI Bill and Yellow Ribbon Program. He graduated from Harvard College in 2012 and subsequently joined the US Coast Guard. After four years of serving aboard cutters homeported in Maine and Puerto Rico, Buddy was medically retired for Type 1 diabetes. His novel, Mona Passage (Syracuse University Press), was published in December.

From Harvard to the “Other” Border (and Back)

The azure waters of the Florida Straits gently rocked the 26-foot-long US Coast Guard interceptor. My shipmate and I, sweating through our navy blue coveralls and bulletproof vests, pulled a young Cuban man aboard. With salt water streaming down his legs and onto the aluminum deck, we fastened an orange life preserver around his torso. In Spanish, I tried my best to explain to the young man and his five friends—their dreams dashed—what was going to happen next.

These young people were just six of the 4,473 Cubans who took to the sea in search of a better life in 2015.

The author aboard Coast Guard cutter Reliance in the North Atlantic in 2013.

I joined the Coast Guard six months after graduating from Harvard College because I wanted to serve my country while remaining connected to Latin America, a region that I had gotten to know through both DRCLAS and stints abroad in Cuba and Mexico. I knew the Coast Guard played a prominent role in the Caribbean, but I didn’t appreciate the scope or complexity of its migrant repatriation mission until I was doing it. As compared to drug interdiction and search and rescue, the migrant mission was—to me—by far the most difficult.

As a Government concentrator, migration had come up frequently in my classes on Latin America. The focus, however, was usually on the southwest border. The human drama that played out daily on the Caribbean Sea was rarely mentioned, an emphasis (or lack thereof) reflected in the broader social discourse.

While migration across the southwest border occurs in greater numbers, migration across the maritime border is a constant flow that periodically swells in response to political disturbances, economic crises, or natural disasters. Generally speaking, this maritime migration manifests itself through three major vectors.

Cutter Reliance during a port call in St. Thomas, USVI in 2014.

(1) Cuba to Florida via the Florida Straits. These journeys usually occur aboard “chugs,” barely seaworthy vessels propelled by car or tractor engines. Under the “Wet Foot, Dry Foot” legal regime that existed until 2016, Cubans who reached US soil could lawfully pursue residency. This incentivized hundreds of thousands of Cubans to attempt the journey, and some of those who were interdicted would harm themselves with blades, gasoline ingestion, or firearms in a desperate attempt to be airlifted to US soil. Numbers are trending upwards again due to a struggling Cuban economy, COVID, and increased political repression.

(2) Haiti to Florida via the Windward Passage. Using sail freighters, large groups of Haitians can catch the trade winds north. Earlier this year, the Coast Guard interdicted one such sail freighter overloaded with 191 Haitians aboard, the rare maritime migration story to garner national headlines.

(3) Dominican Republic to Puerto Rico via the Mona Passage. This journey is made by Dominicans, Haitians, and Cubans aboard primitive motorboats called yolas. Unlike on the Florida Straits or Windward Passage, these trips across the Mona Passage are often carried out by professional traffickers. This year, due to the political unrest in Haiti triggered by the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse, more Haitians have made this journey than anyone else.

Cuban migrant chugs interdicted by cutter Reliance in 2015.

I patrolled all three of these bodies of water, first as a Deck Watch Officer aboard cutter Reliance (Kittery, ME) and then as the Executive Officer of cutter Joseph Tezanos (San Juan, Puerto Rico). I don’t pretend to have the solution to the migration issue, but the lessons I learned while making interdictions and caring for up to one hundred migrants on deck at a time have guided my thinking.

First, most individuals making these journeys are no different than me, my wife, my parents or my brothers and sisters. But they are people attempting to escape something—usually a combination of poverty, violence, and lack of opportunity—to build better lives in the United States. Had I been born on their islands and into their families, I likely would have attempted the same journey.

Second, those Americans patrolling the Florida Straits, Windward Passage and Mona Passage aboard Coast Guard cutters operate with little discretion and considerable empathy. The Coast Guard executes policy—it doesn’t make it. I can’t speak for what happens along the southwest border, but my shipmates and I knew that we had a duty to respect human dignity, and we lived up to that ideal as best we could.

Third, migration will only end when the quality of life in these source countries improves. I don’t know how that happens, but the United States needs to remain committed to the Western Hemisphere to pursue that goal.

Fourth, migration must be regulated. The status quo isn’t the only way to do this, but an open borders policy would be abused by that small but significant group of individuals who have already demonstrated a willingness to harm others. For example, we would run the biometrics of interdicted migrants through a database, and this process would occasionally identify an individual who had already been deported from the United States for a violent felony. These individuals would be separated from the rest of the group to be prosecuted in the United States.

Cutter Joseph Tezanos during a training visit to Key West, FL in 2016.

On a tropical January day in 2017, my life changed. I found out at San Juan’s Veterans Hospital that I had Type 1 diabetes and would be medically retired from the Coast Guard. Five years had passed since my graduation from Harvard, and four since I had been commissioned.

As I waited for the retirement paperwork to clear, I began to write. What began as a way for me to process these sudden changes in my life eventually turned into Mona Passage, a novel about family, friendship, and conflicting duties set against the backdrop of Caribbean maritime migration.

After two years of writing and revising, I caught a lucky break. The novelist Tobias Wolff selected Mona Passage for publication through the inaugural Veterans Writing Award hosted by Syracuse University Press. The book finally came out this past December.

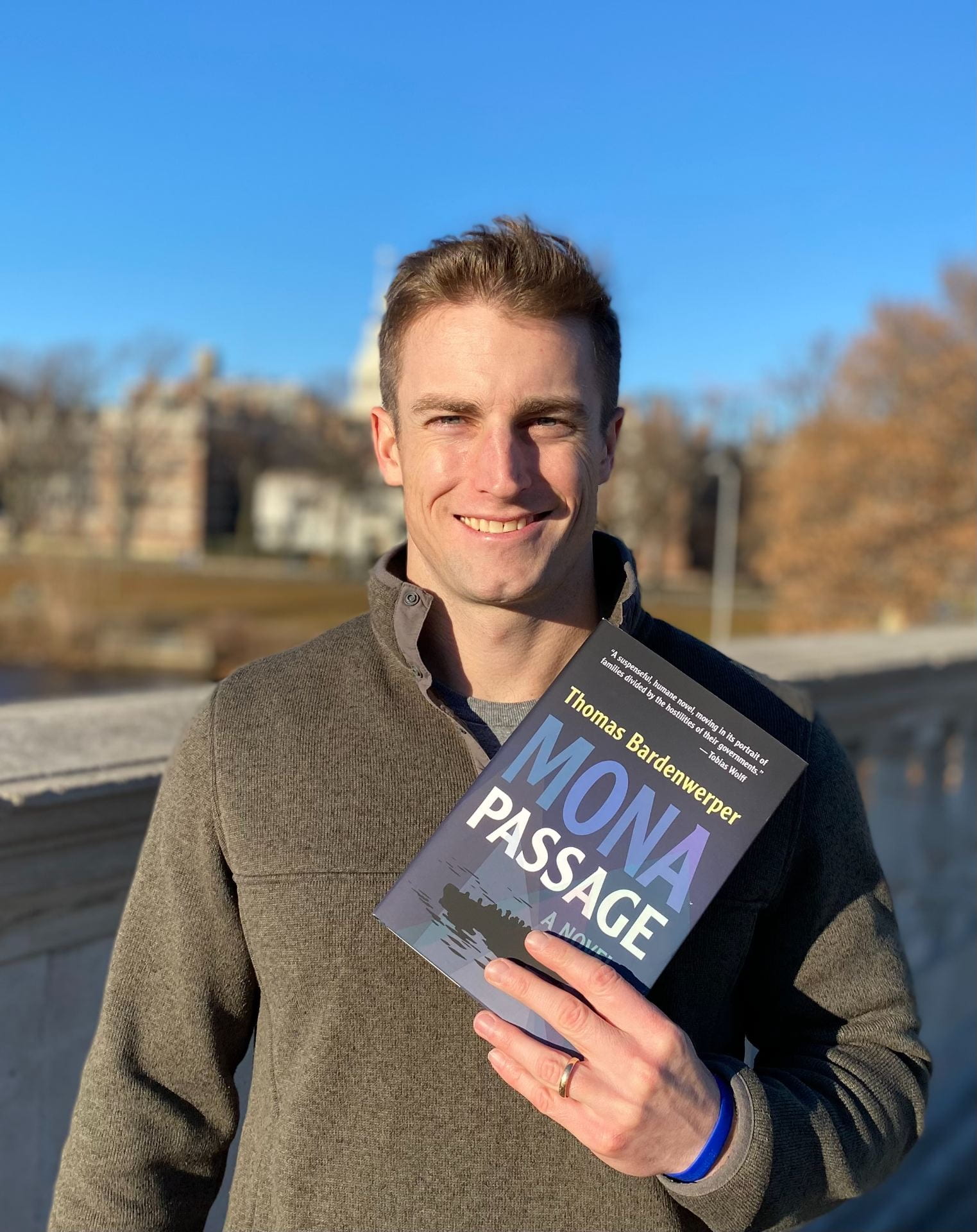

The author back in Cambridge with a just-published copy of Mona Passage: A Novel in 2021.

Not only did writing Mona Passage allow me to end the Coast Guard chapter of my life on my own terms, but it enabled me to perhaps make a bigger difference than I ever could have within the service itself. By telling the story of three people whose lives are forever altered by one journey across the Mona Passage, I will hopefully raise awareness of what is happening on a daily basis in the Caribbean, an awareness that may perhaps lead to a better future.

Thanks to the GI Bill and Yellow Ribbon Program, I’ve returned to Harvard to pursue a joint-JD/MPP. Walking across Harvard Yard brings me back to my pre-Coast Guard days, days that were dominated by football practices and classes with professors such as Steven Levitsky and Davíd Carrasco.

I’ve been extremely fortunate to come full circle, to enjoy privileges that Fredy—the young Cuban man I helped pull from the sea—can only dream of. By recognizing the arbitrariness of all of this—that only luck can explain why I’ve been able to spend eight years at Harvard while Fredy may still be looking for a way out of Cuba—is perhaps the first step to a better future.

Humility leads to empathy, and empathy leads to more humane policy.

More Student Views

Resilience of the Human Spirit: Seizing Every Moment

In the heart of Chicago, where I grew up, amidst the towering shadows of adversity, the lingering shadows of generational demons and the aroma of temptation, the key to the gateway of resilience and determination was inherited. The streets of my childhood neighborhood became, for many, prisons of poverty, plundering, crime and poor opportunity.

Andean Cultural Landscapes in Danger: The Chinchero International Airport

English + Español

Cusco stands as one of the most culturally and ecologically captivating regions globally.

Blossoming Bonds: Beauty and Belonging in Mexico

When I heard the news about my upcoming trip to Mexico, a surge of excitement coursed through me, and I immediately felt the urge to share this exhilarating news with my close friends and family.