Gendered Chocolate Mythologies

From Montezuma to Plain Mr. York

Mr. York as featured in Punch, 30 June 1926

In 1925, the cartoon figure of a portly white gentleman was created to advertise chocolates produced by the English firm of Rowntree & Co, which by this time operated a large factory on the outskirts of the city of York. Given the name “Plain Mr. York, of York, Yorks” and replete in white top hat, sporting a cane, he became a popular interwar marketing device for the Quaker-owned confectionery business. He featured in an early animated film and there was even an animatronic version.

Mr. York was perhaps intended to represent the figure of the kindly, plain-speaking male Quaker industrialist. Yet behind the avuncular Yorkshire masculinity of the Rowntree mascot lies a gendered history of colonialism, and of the exploitation of labour in gendered ways, which can be traced back to the Latin American roots of the cocoa tree. “York” chocolate had its origins very far from Yorkshire—its manufacture absolutely dependent on the labor of women and men in the distant cocoa farms of the British Empire.

Imagining the “Aztec Drink”: Indigenous Consumers and Exotic Masculinity

That cocoa beans ever made their way from South and Central America to the confectionery factories of my home city of York, England, requires some historical explanation. In my own research into the origins of chocolate, I encountered stories already told and re-told many times: mythologies of chocolate, deeply imbricated with gendered tropes of European imperialism. Although the consumption of chocolate in western culture is today most commonly associated with women, it is men who feature prominently in these dramatic tales of its “discovery.”

In 1896, Richard Cadbury—co-owner of the Cadbury Brothers confectionery firm (a Rowntree competitor, though fellow Quakers)—published Cocoa: All About It under the pseudonym “Historicus.” Its frontispiece was a painting of “A Casket of Chocolate being handed to Neptune to make known to all the Countries of the World.”

Fall 2020, Volume XX, Number 1

Poseidon taking chocolate from Mexico to Europe in Chocolata inda by Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma, 1644. National Library of Medicine #2326077R

As Cadbury acknowledged, it was not mythical Neptune but Spanish conquistadors who would be the first to take cocoa beans from their Latin American origins to Europe in the 16th century. The supposed encounter between the reigning Aztec emperor, Montezuma, and the Spanish conquistador, Hernán Cortés, which led to the ‘gift’ of chocolate to the west in 1528, is often presented unproblematically. But Cadbury did not shy away in his text from “the brutality and treachery of Cortés in seizing and holding captive the generous and noble Emperor.” The story of chocolate forms just one aspect of the unpalatable history of colonial violence—the exploitation of both people and resources—that became known as the “Columbian Exchange.”

The positioning of American First Nations peoples as the exotic originators of chocolate is a device which has been used repeatedly to create a marketable mystique around the commodity. In Philippe Dufour’s 17th-century French treatise on the still novel drinks of cocoa, coffee and tea, it is the stylized figure of an Indigenous American man who comes to represent cocoa in the accompanying illustration. Several centuries later, in the 1920s, A. W. Knapp, in his book Cocoa and Chocolate, imagined how cocoa beans were first discovered to be edible by “a pre-historic Aztec with swart [sic] skin,” a man whose name “is blurred and unreadable.”

European tales often emphasise the aphrodisiac qualities of chocolate in the exotic space of Montezuma’s court. According to an early account by one of Cortés’ party, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, the Emperor Montezuma consumed large quantities of cocoa, prepared in golden goblets, and served to him by doting women. It is Montezuma’s excessive love of chocolate that apparently inspired Cortés to take cocoa back to Spain in 1528. Women in these early stories of chocolate tend to appear only at the margins, as sexualized subjects rather than active agents.

“The Romantic Side of Chocolate”: Masculine Adventures and Feminine Consumption

Chocolate has remained a symbolically over-determined product, imbued with tropes of “romance” and ancient mystique. Even the 18th-century scientific classification of cocoa by Swedish botanist Carl Linneaus drew on Aztec mythology: Theobroma Cacao, translated as “food of the gods,” referenced the god Quetzalcoatl who was credited with first planting the cocoa tree in the region. In 1912, the title of British author R. Whympher’s book seemed drily serious: Cocoa and Chocolate: Their Chemistry and Manufacture. Yet Whympher was still seduced by “the romantic side of chocolate”— by tales of “its divine origin, the bloody wars and brave exploits of the Spaniards who conquered Mexico and were the first to introduce cocoa into Europe, tales almost too thrilling to be believed.” Such mythologies of the early history of chocolate are highly gendered, as masculine adventure stories of “discovery” and “conquest.”

While men may seen as the active bearers and producers of chocolate, women are typically positioned as consumers. Tales of chocolate-obsessed women, and of feminized sexual intrigue, infuse histories of early consumption. A common anecdote relates how the European women of Chiapas in Mexico would interrupt religious services to have their hot chocolate brought to them. When the Bishop excommunicated them, they simply moved to another church. The Bishop’s own drinking chocolate was later poisoned. Chocolate becomes explicitly associated with sinful temptation in this tale, with women ruthless in its pursuit.

Rowntree Plantation (Women sitting on ground with cocoa). Reproduced from an original at the Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York. Copyright University of York, not to be used without permission

The most famous “chocoholic” of the early period of European consumption was perhaps Maria Theresa, the wife of Louis XIV, known for her passions for “chocolate and her king” (in that order). Another European noblewoman of the 18th century, Marquise de Coetlogon, was rumoured to have given birth to a black child because she consumed so much chocolate. The mythologized history of chocolate thus allows digression into other tales of racialized sexual scandal and political intrigue. Historian James Walvin’s explanation, in his seminal work, Fruits of Empire, is rather more prosaic, suggesting that the African slave who brought the Marquise her chocolate each morning may have had more bearing on the nature of this tale.

Despite the central place of women in such narratives of European consumption, when chocolate first arrived in Britain it seems to have been confined to the masculine space of the coffee and chocolate houses. Samuel Pepys’ diary entry of 1664, describing “jacolatte” as “very good,” is quoted in virtually every history of the commodity. Chocolate becomes a prop in narratives of 17th-century male bonding and political maneuvering. Although subsequently domesticated and feminized during the 18th and 19th centuries, chocolate remained for a long time the privilege of elites. It took the manufacturing innovations of the later 19th century, alongside reductions in import duties, the exploitation of cocoa farmers (women, men and children) across European colonies, and the labors of an industrial working class, to produce a democratized version of chocolate for Western consumers.

“My Gal’s A Yorkshire Gal”: Yorkshire identity, gendered consumption and women’s labor

Growing up in York in the 1980s, surrounded by the confectionery manufacturing industry and its legacies for the local economy, I would have been hard-pressed to tell you from where chocolate originated. I had certainly never heard of the “Columbian Exchange.” For me, chocolate was Kit Kats, Smarties, Chocolate Oranges and Yorkie bars, with only Terry’s Chocolate Orange even hinting at the tropical origins of cocoa beans in its palm tree logo.

On one occasion, in 1984, caught up in the excitement of the Olympics perhaps, I even transformed myself into a chocolate Marathon bar for the purposes of school fancy dress (I didn’t win and Marathon would later succumb to the pressures of global branding to reemerge as Snickers).

I did know that chocolate manufacture had been an important source of employment, particularly for the women in my family. Yet this too was a history rarely acknowledged in the emphasis on the local male Quaker paternalists of the Rowntree and Terry companies.

In popular imaginings of chocolate, especially chocolate advertising, women are generally positioned as passive consumers rather than active producers. The labor of women in the confectionery factory, or on the cocoa farms that provides its essential raw materials, rarely appears. Only Cadbury seems to have exploited images of its manufacture and workers to any extent, using images of the Bournville “Factory in the Garden,” staffed by women and men in their bright white uniforms, to sell its products in the interwar period.

An early animated film for Mr. York, from 1929, characterized women as lured by chocolate. The short film shows both men and women consuming Rowntree products, but it is a woman who appears in sensuous close up as she places the chocolate bar into her mouth. This young woman rushes out of her terrace house at the call of Mr. York in the street, eats a bar of his chocolate, and then flounces off screen, with her skirt lifting jauntily in the breeze.

Next, Mr. York encounters a male motorist in his broken-down vehicle. The car is repaired with a bar of York Milk, which later provides a convenient make-shift bridge to prevent a car accident—“bridging the gap.” When the car still crashes, the motorist is relieved to find his bar of chocolate unscathed amidst the wreckage. Chocolate was positioned carefully in such advertising as both sustenance and a pleasurable accompaniment to leisure, but stereotypes of feminine and masculine consumption were maintained and reinforced. Men consume chocolate in more active, “rational” ways linked to modern pursuits such as driving.

Madge Munro (Cocoa Works Magazine, Christmas 1932), Rowntree Archives. Reproduced from an original at the Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York. Copyright University of York, not to be used without permission.

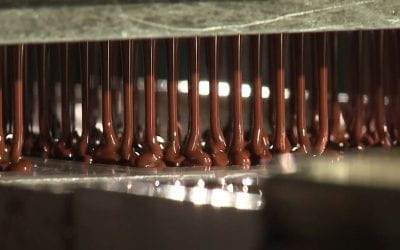

As Mr. York urged consumers to purchase Rowntree’s “York” chocolate, in bars emblazoned with the civic coat of arms, women workers in British West Africa and the British West Indies —like their counterparts elsewhere in the Caribbean, Latin America and other European colonial territories in Africa — toiled to produce cocoa beans and other core ingredients. Within the walls of the York factory, meanwhile, women (who made up more than half the workforce) sorted, packed and decorated a range of Rowntree products. Although parts of the factory were mechanized, the work was still labor intensive. These women had to be skilled and speedy in completing many tasks by hand. Rowntree chocolate assortments, Black Magic and Dairy Box for example, were still arranged in individual paper cups packed by hand, and women were employed to pipe delicate designs onto individual chocolates.

A 1932 film, “Next Stop: York… Help yourself to some chocolates!” did document the labors of women workers at the York factory. The film opened with the sound of women singing in unison at their work in the box-making department, specifically the song, “My Gal’s a Yorkshire Gal.” The identity, and importance, of the Rowntree company as a “local” York firm was thus performed and mutually reaffirmed by the documentary makers and their subjects. Moving quickly away from the women’s work in box making, which is dismissed as a “side line,” the camera comes to focus instead on the work of men mixing the ingredients. The narrator promises to make our mouths water with “some of the real stuff,” implicitly adding value to the work of the men in shot.

Woman Packing, Rowntree collection. Reproduced from an original at the Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York. Copyright University of York, not to be used without permission

Women workers reappear on the screen as the chocolates are decorated and packed. The film’s narrator asserts, “There’s no girl like a Yorkshire girl for dexterity and quickness in squishing out the swirls of rich chocolate.” Yet there is also fascination with the modern technology of the factory: it is the “skillful fingers” of the machines which are said to wrap the chocolates in foil, even as we see women’s hands in shot. We cannot know for sure whether these women workers knew about the distant origins of the cocoa beans, though Rowntree’s occasionally did feature cocoa farmers, including women, in the pages of its journal. In the film, however, it is the image of a decorative box of “Rowntree’s York Chocolates,” adorned with a painting of one of the Roman walls in the city, which appears in the final frame. The tropical associations of cocoa, and its connection with British imperialism, have been entirely erased.

Chocolate remains a source of fascination in Western culture. It has become so imbued with symbolic meaning, so mysterious in its hold over consumers, that even purportedly scientific studies find it hard to detach themselves from the gendered, often sexualized and racialized mythologies surrounding the commodity. In my own research, I wanted to understand how these mythologies of chocolate production and consumption came to exist, and how they have circulated, specifically in relation to the chocolate industry of my own home city of York. My encounter with the Latin American region thus came not through any existing expertise, but through exoticized imperial tales of Spanish “conquest” and “discovery.” From Montezuma to Plain Mr. York, chocolate fictions have too often rendered invisible women’s productive labor and agency at every stage of the chocolate commodity chain.

Emma Robertson is Senior Lecturer in History at La Trobe University, Australia. She is the author of Chocolate, Women and Empire: A Social and Cultural History (Manchester University Press, 2009). Since leaving York for Australia in 2011, she has also published on the role of British women migrants in setting up the Tasmanian Cadbury factory in the 1920s.

Related Articles

Chocolate: Editor’s Letter

Is it a confession if someone confesses twice to the same thing? Yes, dear readers, here it comes. I hate chocolate. For years, Visiting Scholars, returning students, loving friends have been bringing me chocolate from Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru…

El jardín pandémico

English + Español

Imagine the tranquility of a garden. With the aroma of flowers mixed in with the buzzing of bees and the contrast of shady trees against the fierce Paraguayan sun. From the intimacy of a family garden in which daily ritual leads one to water the plants, gather up the dry leaves…

What’s in a Chocolate Boom?

English + Español

Peru has a longstanding reputation for its quality cacao. In the past decade, it has also attracted attention as a craft chocolate hot-spot with a tantalizingly long list of must-try makers. Indeed, from 2015 through 2019, a boom of more than 50 craft chocolate…