Globalizing Latin American Beauty

The Making of a Giant Business

Beauty seems to matter a lot in Latin America. Whenever I arrive in the region I am struck by the disproportionate number of attractive and stylish women and men who seem to be just walking around. I am always even more taken aback by airport bookstalls crammed with magazines devoted to plastic surgery and the celebration of all things beautiful. And then there are the countless posters and billboards advertising beauty accessible to all.

There is plenty of less anecdotal evidence too that beauty is big business. According to the industry database Euromonitor, Brazil is now the fourth biggest market for beauty products in the world, after the United States, China and Japan. Mexico was ranked seventh and Argentina sixteenth.

Even more telling is per capita spending. Brazilian spending on beauty products is $148 on an average for each Brazilian, the highest amount in Latin America. That of Argentina and Chile is just a few dollars less. Although individual Americans and Europeans spend more, Latin Americans stand out among emerging markets as spenders on beauty. Thais, South Africans and Russians spend well under half the amount of Argentines, Brazilians and Chileans. Chinese spend three-quarters less. Indians spend less than one percent than people do in these three Latin American countries.

It is not just lipstick, fragrance and other cosmetic products. Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and Argentina regularly feature in the top ten countries for cosmetic plastic surgery, alongside stalwarts such as the United States and South Korea. Brazil, which offers a tax reduction for such surgery, is a world leader in breast implants and liposuction. Latin Americans are associated with a range of beauty enhancements, from the “Brazilian wax” to “jeans Colombianos.”

In the popular media, the apparent Latin American fascination with beauty is regularly ascribed to culture. Latin sensuousness, cults of body worship in tropical climates, and machismo expectations about female appearance are regularly mentioned. The conservative and religious nature of much of Latin American society rarely gets a mention, however. History points to more complex, and contingent, explanations.

Let me begin with the obvious: Latin America was not the home of the modern beauty industry, nor of plastic surgery. As I explained in my book on the history of the global beauty industry, Beauty Imagined, every known human society in history has used beauty products. Human preferences for adornment and cosmetics were in part shaped by religious beliefs and prevailing medical knowledge. More fundamentally, consumption was probably driven by biological desires to attract and reproduce. Throughout history, beauty products were made in people’s homes, or in small batches by craftsmen. Most people had neither time nor money to devote to beauty. Beauty was also a local matter—standards of beauty varied enormously among geographies, as well as over time.

The advent of modern industry and modern marketing in the 19th century changed everything. Beauty became a business. Skin creams, cosmetics and perfumes began to be made in factories. Chemistry replaced natural ingredients. Advances in understanding the chemistry of scent enabled the creation of synthetic fragrances, transforming the ancient perfume industry in the process. Entrepreneurs created brands. They came up with attractive packaging. They secured endorsements from celebrities. Emotional associations were built around products which had once been functional. Brands offered hope in a jar.

The modern industry was born in the rich industrialized world of Western Europe and the United States. As it grew it incorporated the values and norms of those societies. Beauty became associated with Western appearances with Paris and New York as aspirational global beauty capitals. The features of white people were hailed as the global standard of beauty, and others were considered ugly. In the United States, when beauty contests like Miss America started in the interwar years, African-Americans (and other ethnicities like Jews) were excluded. Beauty was gendered also. Reflecting hardening gender identities in the 19th century, beauty products became associated with women rather than men, which was never the case historically.

The modern beauty industry, along with its underlying ideological assumptions, was brought to Latin America by European and U.S. firms. Only a handful of urban dwellers had incomes and lifestyles sufficient to buy such imported brands. Nineteenth-century prudery and association of cosmetics with immorality also restricted markets. However affluent Buenos Aires, whose citizens famously imagined themselves as located in Europe, became a magnet for French fragrance and cosmetic houses before World War I.

In most of Latin America, however, low incomes and prevailing ethics meant that toilet soap and toothpaste, not color cosmetics, were the first products U.S. and European firms introduced to the region. Unilever, based in Britain and the Netherlands, began making toilet soap in São Paulo in Brazil in 1930, and the business began selling toothpaste in 1939.

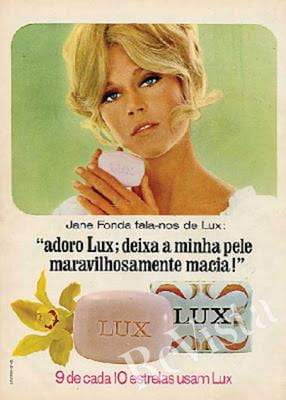

Western multinationals made markets and created consumer desires—they did not respond to a pent-up demand for cosmetic adornment. Marketing strategies were skillfully adjusted to local conditions. In Brazil women seldom read newspapers, the traditional medium used elsewhere by Unilever for advertising. So the firm switched to the more popular medium of radios. Latin American women were enticed with the opportunity to emulate the latest beauty fashions of the United States and Europe. American and European models were used in advertisements by the big cosmetics companies such as Max Factor. However, as Julio Moreno from the University of San Francisco has shown, Ponds cream was advertised using Mexican celebrities during the 1930s, while Colgate-Palmolive, Unilever’s U.S. twin, featured famous Mexican singers such as the Aguilar Sisters on its weekly radio program.

It was Colgate-Palmolive which pioneered the radionovela concept in interwar Cuba, drawing on its promotion of the so-called soap opera radio serials in the United States. It proved an effective tool to grow the market for toiletries in Latin America. The same firm sponsored the first radionovela in Brazil in 1941. The advent of television during the 1950s provided a new medium. A pioneering Mexican telenovela, which became such a distinctive Latin American cultural genre, came in 1958, when Televisa’s Canal 4 showed the Colgate-Palmolive- sponsored Senda prohibida.

As everywhere, U.S. and European firms only celebrated white beauty. The whiteness of the emergent Latin American beauty culture was evident in beauty contests, in which pale skins were exclusively featured. The first national Brazilian beauty contest was held in 1921, only three weeks after the first Miss America, though it was judged entirely on the basis of photographs. The second contest in 1929 appointed a Miss Brazil to represent the country at a Miss Universe contest held in Texas that year, and the final round included taking the state winners through Rio de Janeiro streets, before being judged in Brazil’s largest stadium. The participants and winners were all white. The winner in the first contest had an Italian father.

The privileging of whiteness was the norm of the global beauty industry, but it aligned well with the deep-seated racism throughout Latin America, as well as specific historical trends of the time. There was much discussion about the nature of the Brazilian national identity during the interwar years. The social elite aspired to raise the country’s international status by demonstrating its progress, and that it was becoming more European, defined as ethnically white. The judges in the 1929 contest included university professors, journalists and politicians, and it was chaired by the president of the Brazilian Academy of Letters.

For a long time, Latin Americans remained modest consumers of beauty. Using corporate archives, I have been able to guestimate the historical size of the industry. In 1950 the world industry was worth about $10 billion in today’s dollars—compared to $ 426 billion today. The United States was half the entire world market. Brazil was a mere three percent, although surprisingly this was already half the amount of the richer countries of Britain and France.

The real growth of the beauty market came later in the 20th century. Multinational companies drove market growth. U.S. and European companies devoted increasing attention to Latin America. The region had high tariff barriers, but most countries allowed foreign firms to manufacture and sell locally. This was in big contrast to most of Asia and Africa, where multinational firms were unwelcome, or entirely blocked as in Communist China.

The giants of the U.S. cosmetic industry, whose marketing and advertising expertise had built a huge domestic market, spread over the subcontinent. Revlon opened its first foreign factory in Mexico in 1948. The German hair care company Wella started manufacturing in Chile in 1952, Brazil in 1954, Argentina in 1957, and in Mexico in 1961.

The most important corporate actor was Avon, the company which pioneered direct selling of cosmetics in the United States. In 1954, Avon, whose only previous international operation had been in Canada, opened a new manufacturing business in Puerto Rico. Over the following decade manufacturing and selling operations were started in Venezuela, Cuba, Mexico and Brazil. Direct selling was perfect for Latin America. In most countries, there were few department stores and only fragmented retail channels. Direct selling by sales representatives enabled Avon to reach women in their workplaces and homes.

By 1960 Avon had secured strong market positions in many countries, including Venezuela, where it controlled half of the cosmetics market. Even today nearly one-third of all beauty sales in Latin America are made through direct sales, compared to five percent in Western Europe and less than ten percent in North America. An estimated eighty percent of lipstick sales in Brazil are made by direct selling.

Avon was enormously skilled at enticing people to buy cosmetics. When it entered a new market, it began with acquainting representatives and customers with the Avon line. It provided representatives with the desirable products at good prices, so providing them with an attractive earning opportunity. It tailored its strategy to local circumstances. It invested heavily in cosmetics education in countries such as Venezeula, which at the time used few cosmetics. In Brazil, as historian Shawn Moura has shown, Avon responded to prevailing gender norms which disapproved of women working outside the home with a campaign to portray direct selling as a respectable activity akin to marriage. It also created a new accounting system in response to escalating inflation rates during the 1960s. Avon took a lead in using ethnicities with a range of skin tones in its advertisements. In the United States, the firm was a pioneer in using African-Americans in advertisements from 1966 onwards, though it was not until 1970 that the first Afro-Latinos appeared in advertizements in Brazil. Avon did, however, recruit darker skinned Brazilians as sales representatives much earlier.

Latin Americans were educated and enticed to buy cosmetics, then, by firms which had honed their skills in marketing and business operations in advanced economies. They evidently found willing consumers, but this was at least as much owing to the region’s high levels of income and ethnic inequality than to alleged body cultures or Latin sensuousness. As incomes rose, growing numbers of urban middle class, overwhelmingly white rather than indigenous or Afro-Latino, had money to spend on consumer products beyond essentials. Beauty products were not big ticket items; they delivered instant pleasure; and they were closely associated with the aspirational glamor and economic success of the United States and Europe, to which so many urban Latin Americans were attracted.

Over time, as the beauty business became established, it also acquired a life of its own. Beauty salons and institutes flourished. The beauty industry, although rightly condemned by feminists and others for imposing restrictive ideals of beauty on women and making them constantly dissatisfied, was also a means out of poverty for many Latin American women. They could earn extra income as direct sales representatives or by manicuring nails in tiny salons. Meanwhile winning a beauty contest became the equivalent to winning the lottery. Beauty pageants became big business. As television came to the sub-continent, they attracted good audiences, so television companies invested in promoting them. The Pomona College historian Miguel Tinker-Salas has linked the advent of Venezuela’s large beauty industry to the growth of the Cisneros business group, the owner of the Venevision channel, from the 1980s.

The self-reinforcing nature of the beauty industry is evident in Venezuela, whose citizens became frequent winners of international beauty contests. Avon and Venevision may have created the industry, but over time a whole infrastructure developed to prepare young women for contests through enhancing their appearances, often through surgery or hormones, public speaking skills, and much else. Venezuelan plastic surgeons became world experts in a procedure known as Boom Boom, which injected a woman’s own fat into her buttocks to make them bigger. The chances of appearing, and succeeding, in television reality shows were said to have driven young women to steal to pay for operations. The rewards for winners were dazzling, for careers opened up for them as models and television presenters, and even occasionally in politics.

The fact that the postwar beauty industry came to serve as one avenue for women to enter the workforce and earn incomes was not the only paradox in the Latin American industry. In some respects, the industry became as associated with wellness as with cosmetic adornment.

The levels of cosmetic plastic surgery seen today in the region may justifiably be seen as obsessive, as well as frequently dangerous because of the large informal and illegal component of that industry, but the origins were more benign. Ivo Pitanguy, the founder of the Brazilian industry, earned the respect of his fellow citizens by providing his skills free of charge to victims of a disaster when a huge circus tent burned hundreds of spectators in the city of Niteroi in 1961. Pitanguy was a passionate believer in trying to counter “the stigma of deformity.” Although he built a well-renowned celebrity business, over the following decades he continued to offer his staff and services free of charge to less well-off patients one day a week.

Quite a number of the locally owned cosmetics firms which began to appear in the region had an early and persistent commitment to sustainability, health and societal concerns. An early example was in Colombia. Labfarve laboratories was founded in 1971 by Jorge Piñeros Corpas, a prominent Colombian doctor and scientist, who initially sought to make more affordable medicines for the poorer sections of society using plants and traditional practices, sourcing ingredients from the peoples of the Amazon. The company soon diversified into cosmetics and has made multiple innovations, including developing a natural Botox from an extract of the acmella plant. The wider Corpas Group now includes a hospital and a medical school.

Brazil in particular saw a cluster of local beauty companies formed with health and sustainability concerns. O Boticário was founded in 1977 by Bolivian-born Miguel Krigsner as a small pharmacy in the city of Curitiba in the state of Paraná. Krigsner’s vision was to provide a pleasant environment where people felt good about themselves. The original shop had a carpeted room with seating and coffee for those who wanted to wait while their prescriptions were made up. Krisgner quickly got into cosmetics. In 1979 he opened his brand’s first exclusive shop at Curitiba airport, selling perfume and cosmetics. Within a few years, the small pharmacy had grown to into a big business with 4,000 franchised shops in Brazil targeting the upper-middle segments of the market through eco-friendly products. In 1990, the firm established a non-profit organization to preserve the natural environment.

Social and environmental responsibility was a principal concern of what became the largest Latin American beauty company. Natura was established in 1969 by Antonio Luiz da Cunha Seabra as a small laboratory and cosmetics store in the city of São Paulo. The company adopted a direct selling model in 1974. Guilherme Leal and Pedro Passos later joined the business, forming an unusual three-man leadership, which the company asserted represented its soul, mind and body.

Natura’s direct selling business was a beneficiary of the so-called “lost decade” of the 1980s, as many retailers collapsed, while Natura was able to recruit thousands of female sales representatives who needed a source of income. By 2005, when the firm went public with an IPO, it had revenues of $1.5 billion and employed 480,000 sales consultants throughout the country. By 2017 it had 1.6 billion consultants in Brazil.

Seabra and his colleagues were at the forefront of social and environmental responsibility. In contrast to the perceived stereotypes of Brazilian body-worshipping, Natura criticized exploitative advertising and exaggerated promises. In 1992 the company launched the concept of “The Truly Beautiful Woman” which asserted that beauty was not a matter of age but of self-esteem. This was more than a decade before Unilever’s much-hyped Dove campaign which featured pictures of seniors, larger women and other unconventional beauty models.

Natura was also concerned with the use of sustainable methods and ingredients. In 2000 the company launched the Ekos brand, made from Brazilian biodiversity products in a sustainable way. In 2007 it was a founding member of the non-profit Union for Ethical Bio-Trade. Leal, one of the partners, was personally prominent in the Brazilian section of the World Wildlife Fund, and even stood as the Green Party vice-presidential candidate in Marina Silva’s unsuccessful campaign in 2010. In 2014 the firm became the largest (by then it had sales of $2.6 billion), and first publicly traded company, to obtain B Corp certification, designed to encourage the highest standards of environmental and social stewardship and transparency in business.

Latin America was not preordained by a stereotyped culture to be a temple of beauty. The industry grew at a specific time, and was shaped in a specific way by corporate actors. Its impact was as contradictory as the region itself. It imposed restrictive notions of beauty on generations of women, almost certainly intensified rather than challenged racism, and created cultures in which breast implants and buttocks injections were the societal norm. It peddled unrealistic dreams. Yet it was also an industry which provided income to hundreds of thousands of people, primarily women. And it provided the setting for some of the region’s (and indeed the world’s) most socially and environmentally progressive companies to flourish.

Spring 2017, Volume XVI, Number 3

Geoffrey Jones is Isidor Straus Professor of Business History at the Harvard Business School. His books include Beauty Imagined (Oxford University Press, 2010). His most recent book, Profits and Sustainability: A History of Green Entrepreneurship (Oxford University Press) will be published this spring.

Related Articles

Should I Eat the Chocolate Cake?

English + Español

When people learn that I research the representation of food and weight in Latin American women’s literature, they frequently ask me two questions. The first question is how I became interested in such an untraditional topic…

Technologies of Gender

It was a Tuesday afternoon in early June 2005, and I was sitting with well-known cosmetic surgeon Dr. Julien Martinez (a pseudonym to protect participant confidentiality) in his spa…

Sensual Not Beautiful

While white actresses and models still dominate beauty and fashion magazines in Brazil, on my last few visits to Brazil, I’ve noticed that actresses of African descent such as…