Growing up Jewish in Chile

My Home and Refuge at the End of the World

Photos by Samuel Shats

I grew up Jewish in Chile, that long, narrow country that extends to the very tip of the South American continent. As I listen to the ebb and flow of the waves of the Atlantic where I am right now on the coast of Maine, I reflect on how all of the bodies of water in the world are intertwined and lead us to other places. I imagine the Atlantic taking me back to the ocean of my childhood, the Pacific, to the vitality of its waves, its sounds and its mysteries. I am grateful to both the Atlantic and the Pacific for saving the members of my family who had to leave their countries of origin to escape persecution, first from the pogroms and later from Nazism in the 1930s.

Relatives from both sides of my family crossed the Atlantic in search of refuge, a new country to call home. They were originally from Austria on my mother’s side, and from Russia on my father’s. For many years, they lived happily in cities like Odessa, Vienna and Prague. However, in 1938 the Anschluss took place—the annexation of Austria with Germany—and everything changed dramatically for my relatives who had made their lives in Vienna. While several members of my family perished in the Auschwitz concentration camp, my great-grandmother Helena and her son, Mauricio, escaped to Chile with the help of Helena’s other son, Joseph (my grandfather). He had emigrated to Chile earlier and managed to secure visas for his mother and brother’s safe passage to Valparaíso, the Pearl of the Pacific. Valparaíso is like a balcony overlooking the Pacific Ocean, a balcony that witnessed the arrival of so many people including the pirate Sir Francis Drake and the acclaimed Nicaraguan poet, Rubén Darío.

Descending the stairs

By Marjorie Agosín

You descend the stairs,

A pit in your stomach,

Your ankles trembling.

You are wearing your elegant patent leather heels the color of an aged night,

The Star of David sewn onto your gray overcoat,

Like the gray of that morning.

Slowly, with your habitual grace, you descend the stairs,

Your autumnal hands grasp the iron handrail.

You do not look back

Or study the darkness enveloping you.

Helena and Mauricio escaped the city of Vienna on a Chilean freighter called the Copiapó that departed from Hamburg in 1939. It was a heroic vessel because when the Gestapo boarded the ship demanding to know if any of the passengers on board were Jewish, the brave captain answered with a resounding “No!”

My mother, Frida Halpern, told me that the first time she saw the sea and the port of Valparaíso was when, in 1939, she travelled with her father, Joseph, from where they were living in the southern city of Osorno, to meet the ship that brought Helena and Mauricio to Chile. My mother and grandfather traveled all night by train through the lush forests of Araucanía, a landscape of snowcapped, silent trees that are native to that region. My mother instilled in me her love of Chilean geography and especially Araucanía, which Pablo Neruda referred to as the “Far West” of his country.

When I go to Chile, the smell of the forests of Araucanía and its native woods takes me back in time to imagine and remember the modest wooden house where my mother lived in Osorno with its fireplace and its windows looking out on the world. My grandparents had chosen to settle in Osorno because of its well-established German community that dated back to the middle of the 19th century, and because they believed they would have more economic possibilities there. Beginning in the late 19th century, all of the southern part of Chile, but especially the Llanquihue region and Osorno, had an important German presence. Unfortunately, members of the SS also settled there, making life for the Jewish refugees much more difficult. If the reader would like to learn more about the Nazi presence in Chile, I recommend Victor Farias’ book, Los Nazis en Chile (Seix Barral, 2000) and Carlos Basso’s ChileNazi (Aguilar, 2020).

In Osorno, my grandmother, Josefina, had a small shop where she sold wool, and my grandfather was a traveling salesman. They were one of only four Jewish families living in Osorno at that time. My grandfather used to tell me how he was not allowed to enter the German club until after lunch, because the few Jews who lived there were not permitted to enter before that hour, and my mother told me that she could not attend the German school because she was Jewish. Being Jewish in Chile has always been complicated when it comes to questions of identity and citizenship. It was not until members of my family settled in Valparaíso, much later, that they began to feel more accepted in mainstream society. Nevertheless, even during difficult times when my family felt ostracized, they have always been grateful to their adopted country for allowing them to find a home.

While the number of Jews who emigrated to Chile is small (see Judith Elkin’s The Jews of Latin America, 3rd edition, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2014), they established communities in cities across the country. Over time, they built synagogues, cemeteries and Jewish schools. My grandfather, Joseph, was one of the founders of the Hebrew school in Valparaíso and of the Jebra Kadisha, the sacred society that prepared the dead for their final voyage. But that was later in my family’s story, and I must first finish telling you about Joseph’s mother, Helena.

When Helena and Mauricio arrived in Chile, they began their life in exile in Osorno, but later Helena moved with her son Joseph and his family to Santiago. From the time I was a small child, I heard stories about the great lady from Vienna named Helena. In my earliest memory of her, she is wearing an elegant tulle hat and silk gloves. However, it was only after her death in 1967 that I began to understand many things about her past and started to ask questions about certain topics my family never discussed. As a child I was brimming with questions, but back then children were only to be seen, not heard. Even today, with my clearer understanding of the Holocaust, I still struggle to comprehend that there is such cruelty, such indifference to human life, in the world. It was around the time of Helena’s death that I promised myself to tell her story, which is something I did just recently in a book of narrative poems that includes beautiful photographs by Samuel Shats titled Braided Memories (Solis Press, 2020). The photos in this essay are from that book.

Helena’s story has remained within me like a legacy of love and resilience. I remember that she was small and quiet, and enjoyed reading Rilke and Buber and lighting the Shabbat candles on Friday nights. Those candles were set in candleholders that she brought with her to Chile on the Copiapó. They were objects of her Viennese past that continued to illuminate her life and ours.

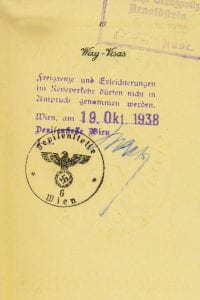

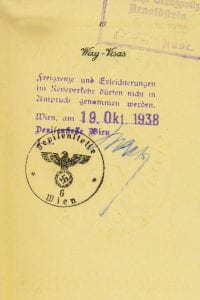

Visa with a Nazi stamp in Helena Broder’s passport. My grandfather Joseph gave Helena’s passport to me when I was 20 years old

I grew up in Santiago across the street from where my maternal grandparents lived. Many languages were spoken in their house. The main one was German, which was how my grandfather communicated with his mother, Helena. My grandmother Josefina spoke Yiddish fluently and German poorly. I remember Jewish families coming to my grandparents’ house to visit. They were from Turkey and Greece, and they spoke Ladino. That language always sounded so beautiful to me. My favorite song at that time was a Sephardic folk song in Ladino titled “Cuando el rey Nimrod,” and I still love to hear that melodious language that has survived into the present thanks to such songs.

During my childhood, I was immersed in both familiar and unfamiliar languages that contained stories about what had happened to my ancestors and our family friends before they arrived in Chile. I listened to the conversations the adults had after dinner with a sense of wonder and fascination, and I would try to decipher the stories they told in their magical languages.

Jews have always been seen as a kind of oddity in Chile and, as such, are also considered “Other.” I remember as a child that we were referred to as “you all” and never as part of “us.” Even though the Jewish immigrants were from diverse places, they were all considered the same. To this day, non-Jewish people do not understand the complexities and diversity of the Jewish people or the difference between Ashkenazi Jews (who originated from Eastern Europe, spoke Yiddish and had their own customs) and Sephardic Jews (who originated from Spain, Portugal, the Middle East, and the northern part of Africa, spoke Ladino and had customs that were different from the Ashkenazi Jews).

Growing up, I always felt as though non-Jewish Chileans put distance between themselves and us. At the same time, however, I know that we distrusted our non-Jewish neighbors out of our atavistic fear of being marginalized. That is why we remained silent and anonymous so no one would learn too much about us. The same is still true today, and the fear persists.

I grew up surrounded by the Andes mountains, the rituals of the Sabbath candles and the silent prayers of my great-grandmother Helena. I also grew up with Catholic nannies who taught me to believe in the magic and beauty of every day and the miracles found in the New Testament. They taught me to knit and to make scarves for the poor to keep them warm in the harsh winters of the southern hemisphere. My nanny, Carmen Carrasco Espindola, taught me how to whip trees one year on the 19th of June—the Night of St. John—, and early one Sunday morning she took my sister and me to get baptized in the Parrish of Nunoa. Carmen Carrasco was afraid that, because I was a Jewish child, I could go to hell if I were not baptized in a Catholic church. My parents thought nothing of it and my wise father told my sister and me not to worry. After all, he said, it was only a few drops of holy water. That is how I grew up, in a kind of hermetic Judaism in which we did not speak of the Holocaust, the servants feared for us for being of a different faith and the upper, educated class barely tolerated the odd Jewish friend.

When I was seven years old, I started attending an English school, the Union School, which was close to my house in the Nunoa district of Santiago. Initially I enjoyed walking the few blocks to the school arm in arm with my mother and sister, because my mother would tell us stories about her childhood and about her father, Joseph. However, one day after school when my mother came to pick me up, she found me crying because my classmates had made me stand in the middle of a circle while they danced around me singing a medieval Spanish song about how a Jewish dog ate the bread from the oven. Mamá spoke with the principal, Ms. Steward, but the latter did not take my mother’s concerns seriously. The early 1960s were not a time of political correctness.

That very night my parents told my sister and me that we were going to switch schools. We would be attending the Hebrew School instead. In that new school, we felt like we belonged from the very first moment, and the atmosphere was filled with happiness. I formed close relationships with my classmates, and we are still close to this day. I learned the Hebrew alphabet and I began to identify more with my Jewish heritage. I think minorities need to belong to communities beyond their own homes, like I did in the Hebrew School. That place gave me the opportunity to belong to an entire people and a history that resembles the great tree of life filled with branches and leaves that intertwine and traverse art, literature, the Torah and the Talmud.

When the military dictatorship came to power in Chile in 1973, everything changed abruptly once again. My immediate family emigrated to the United States, to Athens, Georgia, where there was a lot of discrimination against African Americans and foreigners, especially Jewish foreigners, or “outsiders” as they called us. Separated from my home, I could only discern what was happening in Chile from a distance. All I knew was that it was a country with divided ideologies. Many Jews had left the country earlier when Salvador Allende came to power, thinking that his government would herald in the type of communism they had experienced in Eastern Europe and Russia. Later, others—like my family—left because they did not want to live under Pinochet’s military dictatorship.

What I remember most about the time my family left Chile was the feeling that a great silence blanketed us all. No one spoke about anything, so I had to turn to writing in order to document what was happening. In my journal I would write about the inexplicable and disturbing alliances that had formed in my country, especially between Pinochet and members of the conservative Jewish community. How could my people—the persecuted Jews—be allied with a dictator who tortured and disappeared citizens? How could they invite him and his men to attend services at the synagogues during Yom Kippur? None of this made sense to me.

My fervent passion for human rights, which began when I was a child growing up in a family committed to social justice, crystallized during that time in Georgia. The central beliefs of Judaism like the Tikkun Olam became an essential part of my writing. Tikkun Olam refers to “mending” or “repairing” the world and is often associated with social activism. My work searched for a special kind of alchemy between literature and human rights. It was then that I began to think about writing books to chronicle the experiences of Jewish immigrants. The first two books I published on that topic were about my mother, A Cross and a Star (The Feminist Press at the University of New York, 1997), and my father, Always from Somewhere Else (The Feminist Press at the University of New York, 1998).

Upon reflecting on what it has meant to me to have grown up Jewish in Chile, I am left with an overall feeling of acceptance and hope. I lived a dual existence as a Jewish minority in a Catholic majority, but I nevertheless always felt Chile was my home—the place I love the most and always yearn for—in great part because it gave refuge to my family at a time when the world’s borders were being closed to Jews. Unfortunately, there is still not peace and tranquility for Jews in Chile today. For instance, over the last thirty years, a certain tension has developed between the small Jewish and Palestinian communities. That tension is the result of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians in the occupied territories. There are also divisions in Chile today between progressive Jews and the conservative Jews who supported Pinochet. I hope, with all my heart, that these differences and divisions can be resolved in the near future.

I am writing these words at the end of 2020, the year of the pandemic. I remember with longing and nostalgia that I usually return to Chile around this time in order to see in the new year with my family, gazing at the bay of Valparaíso. We wait for twelve o’clock with our hearts full of emotion to hear the horn blasts from the ships in the bay announcing the end of the old year and the beginning of a new year. Whenever I am there for that special occasion, I think about how so many of my family members arrived in that very same port so many years ago. I am always happy to be there and to imagine my family giving thanks to Chile for saving them from some of history’s worst atrocities. No matter where I am in the world, Valparaíso with its twinkling lights and its houses of many colors, will always be my port, my anchor and my destiny. Perhaps what growing up Jewish in Chile means to me is that I will always have a home in that country at the southern tip of the world.

Crecer como judía en Chile

Mi hogar y refugio al fin del mundo

Por Marjorie Agosín

Fotos por Samuel Shats

Crecí como una niña judía en Chile, ese largo y estrecho país que se extiende hasta el extremo del continente sudamericano. Mientras escucho el vaivén de las olas del Atlántico donde estoy en este momento en la costa de Maine, pienso en cómo todos los mares del mundo se entrelazan y nos conducen a otros lugares. Imagino que el Atlántico me lleva al océano de mi infancia, el Pacífico, a la vitalidad de sus olas, sus sonidos y sus misterios. Agradezco al Atlántico y al Pacífico por haber salvado a mis familiares que tuvieron que salir de sus países de origen para escaparse de la persecución, primero de los pogromos y más tarde del nazismo en los 1930.

Mis parientes de ambos lados de mi familia cruzaron el Atlántico en busca de un refugio, un nuevo país donde sentirse en casa. Eran de Austria por el lado materno de mi familia y de Rusia por el lado paterno. Vivieron felices en ciudades como Odessa, Viena y Praga por muchos años. Sin embargo, en 1938 ocurrió el Anschluss—la anexión de Austria con Alemania—y todo cambió radicalmente para mis parientes que vivían en Viena. Mientras que varios de ellos perecieron en el campo de concentración, Auschwitz, mi bisabuela Helena y su hijo, Mauricio, huyeron a Chile con la ayuda del otro hijo de Helena, Joseph (mi abuelo). Él había emigrado a Chile unos años antes y pudo conseguir visas para que su madre y su hermano viajaran a Valparaíso, la Perla del Pacífico. Valparaíso es como un balcón que da al mar Pacífico, un balcón que presenció la llegada de tantas personas, entre otros el pirata Francis Drake y el aclamado poeta nicaragüense, Rubén Darío.

Bajando las escaleras

Por Marjorie Agosín

Bajas las escaleras,

Un hueco en el estómago,

Un temblor en los tobillos.

Llevas tus elegantes tacones de charol color noche envejecida,

La estrella de David cosida al abrigo gris

Como el gris de ese amanecer.

Lenta, con tu habitual gracia, bajas las escaleras,

Tus manos de otoño sujetan las rieles de fierro,

No miras hacia atrás,

Ni a la oscuridad que te rodea.

Helena y Mauricio se escaparon de la ciudad de Viena en un barco de carga llamado el Copiapó que salió del puerto de Hamburgo en 1939. Fue un barco heróico porque cuando se subió la Gestapo al barco preguntando si los pasajeros abordo eran judíos, el capitán valiente les dio un rotundo “¡No!”.

Mi madre, Frida Halpern, me contó que la primera vez que vio el mar y el puerto de Valparaíso fue en 1939 cuando viajó con su padre Joseph, desde donde vivían en el sur de Chile en la ciudad de Osorno, para recibir a la embarcacion que llevó a Helena y Mauricio a Chile. Mi madre y mi abuelo viajaron en un tren nocturno por los frondosos bosques de la Araucanía, un paisaje lleno de árboles nativos, ventisqueros y silencios. De mi madre aprendí a amar la geografía de Chile, y en especial la de la Araucanía, la zona que Pablo Neruda llamó el Far West de su patria.

Cuando viajo a Chile, la fragancia de los bosques de la Araucanía y sus maderas nativas me hacen imaginar y recordar otra época cuando mi madre vivía en Osorno en una casa modesta de madera con su chimenea y sus ventanas que daban al mundo. Mis abuelos decidieron instalarse en Osorno por la ya establecida comunidad alemana que había llegado a mediados del siglo diecinueve y porque pensaban que en esa ciudad tendrían mejores oportunidades económicas. A partir de finales del siglo 19, todo el sur de Chile, pero en especial la zona de Llanquihue y Osorno, tuvo una importante presencia alemana. Desafortunadamente, miembros de la SS también se instalaron allí y la vida de los refugiados judíos se hizo más dura. Si el lector quiere aprender más sobre la presencia nazi en Chile, le recomiendo los libros Los Nazis en Chile por Victor Farias (Seix Barral, 2000) y ChileNazi por Carlos Basso (Aguilar, 2020).

En Osorno, mi abuela, Josefina, tenía una pequeña tienda donde vendía lanas y mi abuelo era vendedor ambulante. Ellos eran una de solo cuatro familias judías que vivían en Osorno en aquel entonces. Mi abuelo me contaba que no lo dejaban entrar al club alemán hasta después del almuerzo porque los escasos judíos no podían entrar antes de esa hora, y mi madre me dijo que no le permitieron asistir al colegio alemán por ser judía. Ser judío en Chile siempre ha sido complicado respecto a cuestiones de identidad y ciudadanía. No fue hasta que algunos miembros de mi familia se instalaron en Valparaíso que empezaron a sentirse como parte de la mayoría de la sociedad. Sin embargo, aun durante épocas cuando mi familia se sentía excluida, siempre han sentido agradecimiento por su país adoptivo que les permitió encontrar un hogar.

Mientras que el número de judíos que emigraron a Chile es pequeño (ver The Jews of Latin America, 3a edición por Judith Elkin, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2014), lograron establecer comunidades en ciudades por todo el país. Con el pasar del tiempo construyeron sinagogas, cementerios y escuelas judías. Mi abuelo, Joseph, fue uno de los fundadores del colegio hebreo de Valparaíso y de la Jebra Kadisha, la sociedad sagrada que prepara a los muertos para su último viaje. Pero esto ocurrió más tarde en la historia de mi familia y necesito seguir contando la historia de la madre de Joseph, Helena.

Cuando Helena y Mauricio llegaron a Chile, empezaron su vida en el exilio en Osorno, pero más tarde Helena se mudó con su hijo Joseph y su familia a Santiago. Desde niña escuché historias sobre esta gran dama de Viena llamada Helena. En mi primer recuerdo de ella está llevando un refinado sombrero de tul y guantes de seda. Sin embargo, fue solo después de su muerte en 1967 que empecé a entender muchas cosas acerca de su pasado y comencé a hacer preguntas acerca de ciertos temas de que mi familia nunca hablaba. De niña tenía tantas preguntas pero en aquel entonces los niños debían ser vistos no escuchados. Incluso hoy con mi conocimiento más nítido del Holocausto, me cuesta entender que hay tanta crueldad e indiferencia a la vida humana en el mundo. Fue en la época en que Helena murió que me prometí a mí misma contar su historia, y lo hice recientemente en un libro de poemas narrativos que incluye hermosas fotografías por Samuel Shats llamado Memorias trenzadas (Solis Press, 2020). Las fotos en este ensayo son de ese libro.

La historia de Helena ha permanecido en mí como un legado de amor y de resilencia. La recuerdo siempre diminuta y silenciosa. Le gustaba leer a Rilke y a Buber y encender cada viernes las luces del Shabat. Ella trajo estos los candelabras con ella cuando viajó a Chile en el Copiapó. Eran objetos de su pasado vienés que siguieron iluminando su vida y la nuestra.

Visa con sello nazi en el pasaporte de Helena Broder. Este pasaporte me lo dio mi abuelo Joseph cuando tenía 20 años

Crecí al otro lado de la calle donde vivían mis abuelos maternos en una casa donde se hablaban muchos idiomas. El principal era el alemán, que era cómo se comunicaba mi abuelo con su madre, Helena. Mi abuela Josefina hablaba yidish con soltura y un mal alemán. Recuerdo que muchas veces las familias judías llegaban a la casa de mis abuelos de visita. Eran de Turquía y de Grecia y hablaban ladino. Ese idioma me parecía tan bello. Mi canción favorita en aquel entonces era una canción folclórica sefardí en ladino, “Cuando el rey Nimrod”, y todavía me gusta oír ese idioma melodioso que ha sobrevivido gracias a tales canciones.

Mi infancia transcurrió entre esos idiomas lejanos y cercanos que contenían historias acerca de lo que les ocurrió a mis antepasados y los amigos de la familia antes de la llegada a Chile. Escuchaba las conversaciones de los adultos en la sobremesa con un sentimiento de asombro y fascinación, e intentaba decifrar las historias que contaban en sus idiomas mágicos.

Los judíos siempre se les ha percebido con cierta curiosidad en Chile y como tal también se consideran como “los otros”. Recuerdo de niña que siempre nos decían “ustedes” y nunca formábamos parte del “nosotros”. Aunque los inmigrantes judíos eran de lugares tan distintos, todos se consideraban iguales. Hasta hoy en día la gente no judía no entiende la complejidad y la diversidad de los judíos o la diferencia entre los judíos asquenazi (oriundos de la Europa oriental, hablaban yidish y tenían sus propias costumbres) y los judíos sefardíes (oriundos de España, Portugal, el Medio Oriente, y la parte norte de África, hablaban ladino y tenían costumbres distintas a las de los judíos asquenazi).

A lo largo de mi niñez sentía que los chilenos no judíos siempre ponían cierta distancia entre ellos y nosotros. Sin embargo, al mismo tiempo sé que nosotros no confiábamos siempre en nuestros vecinos no judíos por ese atavico temor nuestro a ser discriminados. Por eso nos mantuvimos en silencio y en una anonimidad para que de nosotros nada se supiera. Aún hoy en día esto ocurre y los temores son similares.

Me crié rodeada de la cordillera de los Andes, los rituales de las velas del Shabat y los rezos silenciosos de mi bisabuela Helena. También me crié entre las nanas católicas de la casa, las que me enseñaron a crear en la magia y la belleza de lo cotidiano y los milagros del Nuevo Testamento. Con ellas aprendí a tejer, a hacer bufandas para los pobres para abrigarlos durante los duros inviernos del hemisferio sur. En un 19 de junio—la noche de San Juan—, mi nana, Carmen Carrasco Espindola, me enseñó a azotar los árboles, y un domingo muy de amanecida me llevó a mí y a mi hermana a bautizarnos en la parroquia de Nuñoa. Carmen Carrasco tenía miedo que yo, como una niña judía, me pudiera ir al infierno por no ser bautizada en una iglesia católica. Mis padres lo tomaron con una gran serenidad y mi sabio padre nos dijo a mi hermana y a mí que no importaba, que tan solo era un poquito de agua bendita. Así crecí entre una especie de judaísmo hermético donde no se hablaba del Holocausto, donde las sirvientas tenían temor por nosotros por ser de otra fe y donde la clase alta y educada chilena apenas toleraba a uno que otro amigo judío.

A los siete años fui a un colegio inglés llamado el Union School que quedaba muy cerca de mi casa en el distrito de Nuñoa en Santiago. Al principio me gustaba caminar esas cuadras del brazo de mi mamá y mi hermana porque mi mamá nos contaba historias de su niñez y de su padre, Joseph. Pero un día después de la escuela cuando mi madre vino a recogerme, me encontró llorando porque mis compañeras me habían puesto en el medio de una ronda mientras bailaron alrededor de mí cantando una canción de origen medieval español que decía que el perro judío se había comido el pan del horno. Mamá habló con la directora, la señorita Steward, pero ella no lo tomó en serio. En los años tempranos de los 1960 no existía la corrección política.

Aquella misma noche mis padres nos dijeron a mi hermana y a mí que íbamos a cambiar de colegio al Instituto Hebreo. En ese colegio pertenecimos desde el primer momento y había una atmósfera llena de alegría. Sentí un gran compañerismo por mis amigos de ese colegio que me acompañan hasta ahora. Aprendí el alfabeto hebreo y empecé a identificarme más con mi herencia judía. Pienso que las minorías necesitan sentir que pertenecen a comunidades más alla de sus casas, como yo me sentía en el Instituto Hebreo. Ese lugar me brindó la oportunidad de pertenecer a todo un pueblo con una historia que se parece al gran árbol de la vida lleno de ramas y de hojas que se entrelazan y caminan a través del arte y la literatura, la Torah y el Talmud.

Cuando llegó la época de la dictadura militar en Chile en 1973, todo cambió radicalmente otra vez. Mi familia emigró a los Estados Unidos, a Athens, Georgia, donde había mucha discriminación contra los afro-americanos y los extranjeros, y especialmente los extranjeros judíos, o “los de afuera” como nos llamaban. Alejada de mi hogar, solo pude percibir lo que estaba pasando en Chile a una distancia. Lo único que sabía fue que Chile era un país con ideologías divididas. Muchos judíos se habían ido antes, con la llegada del gobierno de Salvador Allende, porque pensaban que el comunismo como lo que habían experimentado en la Europa del este y Rusia llegaría a Chile. Más tarde, otros—como los miembros de mi familia—se fueron porque no quisieron vivir bajo el gobierno militar de Pinochet.

Lo que más recuerdo de la época cuando mi familia se fue de Chile es que sentía que un gran silencio nos envolvía y que nadie hablaba de nada. Fue por eso que empecé a escribir para documentar lo que pasaba. En mi cuaderno escribía sobre todas las alianzas inexplicables y perturbadoras que se habían formado en mi país como las de Pinochet y la parte conservadora de la comunidad judía. ¿Cómo fue posible que mi pueblo judío y tan perseguido formara alianzas con un dictador que torturaba y desaparecía a sus ciudadanos? ¿Cómo fue posible que les permitiera a Pinochet y sus hombres asistir a los servicios en las sinagogas en Yom Kippur? Esto no tenía ningún sentido para mí.

Mi pasión por los derechos humanos—que empezó cuando era niña porque crecí con una familia dedicada a la justicia social—se cristalizó en esa época en Georgia. Las creencias centrales del judaísmo como el Tikkun Olam se hicieron una parte escencial de mi actividad como escritora. El Tikkun Olam se refiere a “remendar” el mundo y muchas veces se asocia con el activismo social. Toda mi obra BUSCA la alquimia entre la literatura y los derechos humanos. Fue a través de esta experiencia que empecé a pensar en escribir libros para documentar las experiencias de los inmigrantes judíos. Los primeros dos libros que publiqué acerca de ese tema fueron libros de memoria sobre mi madre, A Cross and a Star (The Feminist Press at the University of New York, 1997) y mi padre, Always from Somewhere Else (The Feminist Press at the University of New York, 1998).

Al reflexionar sobre lo que ha significado crecer como una niña judía en Chile, me quedo con un sentimiento de aceptación y esperanza. Viví una doble existencia como parte de la minoría judía junto a una mayoría católica, pero de todos modos siempre sentía que Chile era mi casa—mi lugar amado y siempre anhelado—en gran parte porque es la patria que les dio refugio a mis familiares en una época cuando las otras fronteras del mundo se cerraban para los judíos. Desafortunadamente, todavía no hay paz y tranquilidad para los judíos en Chile. En los últimos treinta años cierta tensión ha crecido entre las pequeñas comunidades judías y palestinas. Esa tensión ha sido motivada por el trato de Israel hacia los palestinos en los territorios ocupados. Además hay divisiones entre la comunicad judía progresista y la más conservadora, la que apoyó a Pinochet. Espero con todo mi corazón que esas diferencias y divisiones se puedan resolver pronto.

Escribo estas meditaciones a fines del 2020, año de la pandemia. Recuerdo con nostalgia y añoranza que siempre en estas fechas regresaba a Chile y pasaba el año nuevo mirando la bahía de Valparaíso con mi familia. Esperamos las doce con nuestros corazones llenos de emoción para escuchar las sirenas de los barcos que anuncian la llegada del fin del año y el principio del año nuevo. Cada vez que estoy allí para esa celebración especial pienso en los miembros de mi familia que llegaron a ese mismo puerto hace tantos años. Siempre me siento feliz por estar allí e imagino a mis parientes dándole gracias a Chile por haberlos salvado de unas de las peores atrocidades de la historia humana. Donde sea que esté o me encuentre, Valparaíso con sus luces titilantes y sus casas pintadas de dulces colores, será siempre mi puerto, mi ancla y mi destino. Quizás crecer judía en Chile significa para mí siempre tener un hogar en ese país al fin del mundo.

Winter 2021, Volume XX, Number 2

Marjorie Agosín is a Chilean-American poet, novelist and human rights activist. She is the author of more than fifty books that include narrative poetry, theatre and memoirs. Her acclaimed young-adult novel I Lived on Butterfly Hill was the winner of the Pura Belpré Prize. Marjorie teaches Spanish at Wellesley College in Massachusetts.

Alison Ridley is Marjorie’s translator. She is a Spanish professor at Hollins University in Roanoke, Virginia.

Marjorie Agosín es una poeta chilena-americana que también es novelista y activista por los derechos humanos. Es autora de más de cincuenta libros que incluyen poesía narrativa, teatro y memorias. Su aclamada novela juvenil, I Lived on Butterfly Hill, ganó el Premio Pura Belpré. Marjorie enseña español en Wellesley College en Massachusetts.

Related Articles

El Salvador, Back in the Day

The glory days are long gone. They began in the 70s. Extraordinary grassroots pastoral work, accompanied by a then-new school of thought known as “liberation

Christianity between Religious Transformations

English + Español

In the second half of the 20th century, Latin America was surprised by religious changes that not only were transforming the religious panorama, but also influencing both society and politics. Beginning in the 1950’s, some in the Catholic Church—not just priests and…

The Mexican Angels in the Attic

Years before I met the Mexican angels in that Chicago attic, my abuela Carlota Carranza Carrasco told me about religion. Carlota was born in Batopilas at the bottom of the Cañon del Cobre in 1896 and crossed the border into El Paso to escape the chaos of the Mexican Revolution in 1912…