Guarani in Film

Movies in Paraguayan Guarani, about and with Guaranis

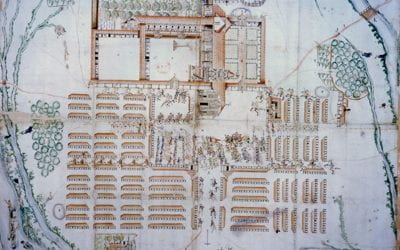

A contemporary film featuring the Guarani: Paz Encina. Hamaca Paraguaya. 2006. Photo by Christian Núñez, courtesy of Damián Cabrera.

The first film spoken in Guarani I ever saw was from the United States. It was the movie Jesus (1979), co-directed by Peter Skyes and John Krish, dubbed into Guarani and customarily broadcast on television during Holy Week in Paraguay. My generation had not grown up seeing ourselves on the screen. With films like Hamaca Paraguaya (Paraguayan Hammock, 2006) by Paz Encina or 7 cajas (7 Boxes, 2012) by Juan Carlos Maneglia and Tana Schémbori respectively, films in Guarani are now achieving international projection as well as local popularity. Today we Paraguayans can see ourselves on the screen and listen to ourselves— in our own languages.

In Paraguay, speaking Guarani is charged with ambiguity: it evokes both fondness and contempt. In Spanish slang, the word guarango—the contemptuous nickname for those who speak Guarani—means “rude, vulgar.” It’s as if the use of the language were somehow a mark of vulgarity. However, at the same time, others celebrate “the sweet Guarani language” as the most important legacy of the Guarani culture to Paraguayan society. An indigenous language, from the linguistic family Tupí-Guaraní, Guarani is today spoken in Paraguay by the largely non-indigenous population.

“The history of Paraguay is the history of the Guarani language,” says the anthropologist Bartolomeu Melià in his book Mundo Guaraní (Guarani World, 2011). The history of Paraguay is also one of prohibition of this language and the assumed exclusion that came from speaking it. But it is the history of persistence.

In an emerging and increasingly prolific scene in Paraguayan film, Paraguayan Guarani is being heard at the international level, making visible its history. But does speaking Guarani mean being Guarani? Perhaps the new cinematic movement gives us the opportunity to reflect on these questions, both in terms of the status of the language and of the various types of belonging associated with Guarani: the indigenous world, the Paraguayan peasant and the urban dweller.

GUARANI IN FILM ALSO HAS ITS HISTORY, AND NOT SUCH A RECENT ONE

“The first films in Guarani were silent,” observed actor and writer Manuel Cuenca, author of Historia del Audiovisual en Paraguay (A History of the Audiovisual in Paraguay) (2009), in which he details the country’s film production. Since the beginning of the 20th century, 35-millimeter movies—silent, in black and white—have depicted Paraguay’s indigenous and peasant communities, with protagonists who sing or speak in Guarani. Codicia (1954), by Argentine director Catrano Catrani, was the first spoken fiction film to incorporate dialogues in Guarani. Basing his work on the Paraguayan novelist Augusto Roa Bastos, who also wrote his own adapted screenplays, Armando Bó produced La sed (1961) and El trueno entre las hojas (1975); in which, in addition to dialogues, one can also hear a song in Guarani, “Adiós Lucerito Alba” by Eladio Martínez. (Isabel Sarli’s nude scenes in this film made her famous, and she appeared again in India (1961) and La burrerita de Ypacaraí (1962), by Bó.) La sangre y la semilla(1959) was the first Paraguayan-Argentine co-production. Palestinian director Dominique Dubosc filmed his first works in Paraguay at the end of the 60s. Capturing the voices of his protagonists with a poetic tone, he depicts the life of a Paraguayan peasant family and that of the Santa Isabel lepers’ colony respectively in Cuarahy Ohechá (Le soleil l’a vu) (1968) and Manojhara (1969).

Although several films are about Guarani or include them in the narrative, many have used other indigenous groups or even non-indigenous actors to represent them. In his films that reference the Guaranis, Bó used Paraguay’s Maká tribe, which in reality form part of the Mataco linguistic group. In the first scenes of India, the lyrics of a song announce “india Guarani…,” with the Argentine actress Isabel Sarli depicted as an indigenous woman; paradoxically, it is not difficult to find in schoolbooks photographs of the indigenous Maká group with captions indicating that they are Guarani.

Robert De Niro and Jeremy Irons were the principal actors in a story based on the original Jesuit missions in Paraguay, The Mission (1986), directed by Roland Joffe and with music by Italian composer Ennio Morricone. In spite of my efforts, I could not recognize the “guarani” spoken by the indigenous actors in the movie and not even the words uttered by Irons. The Mission was not filmed in Paraguay: the scenes supposedly taking place in Asunción were filmed in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia; one of the film locations was at Iguaçu Falls in Brazil; the indigenous people are not Guarani; for the most part, they are indigenous Waunanas from the Colombian Pacific region of Chocó. But the gap is not as great as it seems: an Argentine indigenous leader, Asunción Ontiveros, plays a Guarani chieftain; in the accompanying explanation of the making of the film, entitled Omnibus: The Mission, Ontiveros spells out the common problems shared by the Waunanas and the Guarani, and indeed all the indigenous peoples of the Americas: the land.

Although all fall under the umbrella of Guarani, there is actually more than one Guarani language; and although some of these languages are called something else, they are as Guarani as the others, identical in spite of their differences. In Hans Staden (1999) by Luis Alberto Pereira, the Tupinambá indigenous people are played by non-indigenous actors. Based on Staden’s stories and spoken in classic Tupí (of the Tupí-Guarani linguistic family), the film has realist pretensions: the director insists on a type of neutral stance devoid of interpretation (unlike other films that examine the same theme), but it is based on a previous text, a testimonial discourse saturated with interpretation; thus, the representation of the indigenous people—more than the story itself—reminds us of the blackface tradition in U.S. film at the beginning of the 20th century.

Aren’t there any Guarani actors? Yes, there are: one can see them in Terra Vermelha (Birdwatchers, 2009) by Marcos Bechis. This is the drama of the Guaraní-Kaiowa (known as Pãi Tavyterã in Paraguay) on the border of Paraguay and Brazil. They play themselves in their own language to show the threat agro-business poses for their way of life, with suicide by young people becoming an increasing social trauma. The drama portrayed in the narrative turns out to be real: indigenous leader Ambrósio Vilhalva (Chief Nádio in the film) acts out his death, and less than a year later, he was assassinated in real life.

Indigenous people are represented by others or exposed to the gaze of others. But perhaps this reality will soon change. With a language that belongs to the same linguistic family as that of the Guarani, the Aché have been shooting films. Norma Tapari and Ricardo Mbekrorongi made the documentaries Nondjewaregi/Costumbres antiguas (2012) and Tõ Mumbu (2012), respectively, in which they gathered oral histories from their grandparents, in the context of the djawu/Aché Word project, which seeks to rescue Aché culture through literary production, photography and audiovisual documentation.

THE GUARANI IN CONTEMPORARY PARAGUAYAN FILM

Is this my voice? It’s like hearing oneself for the first time in a recording, to see oneself finally reflected on the screen. Hamaca Paraguaya is the first Paraguayan film I’ve seen. The experience was extraordinary, and so was the film. Journeying through history, it presents an image of time: the idea of a flickering, vacillating waiting/hope (which in Spanish happens to be the same word: esperar) that goes back and forth but always stays in the same place, despite the instability. The circular dialogues are inscribed in a scene equally structured in a circular fashion. In Hamaca, there is a desire to represent Paraguayan time, which perhaps can be imagined as a crossroads with another temporal memory, that of oguatáva (caminante/walker). Guaraní is present in the jeroky ñembo’e, which is at the same time a prayer and a dance, equally circular.

Paraguay experienced a rough period following the Curuguaty massacre on June 15, 2012, during a police raid on homeless peasants; the confrontation took 17 lives, and spurred a congressional coup, disguised as a political trial, that resulted in the impeachment and removal from office of then President Fernando Lugo. For some viewers, watching 7 cajas, which treats this period, is a cathartic experience. For several months, movie theaters were full. When I went, the social phenomenon spoke (literally) as loudly as the movie itself. Spectators were noisy, laughing at the top of their lungs and applauding; the theater was filled with the excitement of self-recognition.

Beyond the story, its portrayed and imagined universe and its use of language, 7 cajas can be understood as a metaphor. It’s not only a matter of showing the only mechanisms the poor can resort to in order to circulate their own images in the overloaded market of images. A scene of emergencies also reveals something about the conditions in which the Paraguayan filmmaker operates: the character Victor could be just another filmmaker looking for resources to produce images and put on the screen his stories, and in that very process, become someone.

These two Guarani films are the best known on the international level, but they are not the only ones. And there are more on the way.

In 2002, Galia Giménez premiered María Escobar, based on a song in Guarani by the same name, very popular at that time among all social classes. The short subjects Karai Norte (Man of the North, 2009) by Marcelo Martinessi and Ahendu Nde Sakupái (I hear your scream, 2008) by Pablo Lamar are two masterpieces of Paraguayan film. The recently premiered Latas vacías (Empty Cans, 2014) by Hérib Godoy and Costa dulce (2013) by Enrique Collar take up the theme of pláta-yvyguy (treasures buried during the 19th-century war, a subject that has fired the Paraguayan imagination through prolific works of art); both films are spoken in peasant Guarani, and the action takes place outside Asunción, with regional actors who have not attended traditional acting school, thus providing a fresh voice to new Paraguayan film. Meanwhile, Luna de cigarras (Cicadas’ Moon, 2014) by Jorge Díaz de Bedoya, in which Guarani is shown along in the border zone, along with Spanish and Portuguese, has been nominated for Spain’s Goya Awards.

In the documentary realm, Guarani has flourished in an extensive list that ranges from the patrimony of the silent era to acclaimed pieces that register peasant and indigenous voices such as Tierra roja (Red Land, 2006) and Frankfurt (2008) by Ramiro Gómez; or Fuera de campo (2014) by Hugo Giménez. In Yvyperõme(2013) by Miguel Armoa, the declarations of a Guarani shaman, proclaiming that “before we were the wizards of the woods; now we are the wizards of soybeans,” testifies to the traumatic and transformative times Paraguay is experiencing.

Stigma and prohibitions on Guarani had threatened its existence, and the transmission from one generation to another was seen as difficult. Wouldn’t the fact that the mainstream media talk and write in Spanish, rather than Guarani—despite the fact that the majority of Paraguayans speak Guarani or are to a certain degree bilingual—have something to do with that?

In 2015, the film Guaraní, by Argentine director Luis Zorraquín, will have its premiere. Not only is it spoken almost entirely in Guarani; the movie itself is about the Guarani language. The film and the journalistic treatment of the subject to date can serve to explore the ambivalence surrounding Guarani today: the variations of Guarani of the Guarani indigenous people and the Guarani of the Paraguayans. John Hopewell suggests in the magazine Variety that the film is about questions and identity in a narrative featuring “a traditionalist Guarani fisherman, and his grand-daughter.” A Spanish News Agency EFE dispatch published in Paraguay’s ABC Color de Paraguay confirms that the film is about “a story of the uprooting and survival of the Guarani indigenous culture.” Both reviews are mistaken: the film is the story of a Paraguayan and his finding strength in the language in a bet on the future.

But what does all this lack of clarity mean? The word guarani signifies a lot: it is the name of a language and the name for a culture; sometimes it is used as an ethnic nickname for Paraguayans; it’s the name of stores, diet teas and sports clubs.

The persistence of Guarani in a society that is more western than indigenous is also ambivalent: the secondary language of Paraguay, its hegemony seems inconsistent in a country that vehemently rejects all that is indigenous. But the “discourtesy” of its resistance is felt more strongly all the time, overcoming the silence also of the big screen, where Guarani is spoken louder and louder. Every single time, louder and louder.

Guarani en el Cine

Películas en guaraní paraguayo, sobre Guaraníes y con Guaraníes

Por Damián Cabrera

Una película contemporánea : Paz Encina. Hamaca Paraguaya. 2006. Foto de Christian Núñez, Cortesía de Damián Cabrera .

La primera película en guaraní que he visto es estadounidense. Se trata de Jesus (1979), co-dirigida por Peter Skyes y John Krish, doblada al guaraní, y que es habitualmente retransmitida en las programaciones televisivas de Semana Santa en Paraguay. Mi generación no ha crecido viéndose en las pantallas. Con películas como Hamaca Paraguaya (2006) de Paz Encina o 7 cajas (2012) de Juan Carlos Maneglia y Tana Schémbori se ha animado una instancia de proyección internacional, pero también local: hoy los paraguayos podemos vernos en pantalla, y escucharnos. En nuestras propias lenguas.

En Paraguay, hablar guaraní ha estado marcado por signos ambivalentes de afecto y desprecio. En castellano, la palabra guarango significa “incivil, grosero”, y es el apodo despectivo que reciben quienes hablan guaraní, como si ello constituyese una marca de vulgaridad; pero también hay quienes celebran la así llamada “dulce lengua guaraní” como el legado más importante de la cultura Guaraní a la sociedad paraguaya; lengua indígena, de la familia lingüística Tupí-Guaraní, hablada hoy por una población mayoritariamente no-indígena.

“La historia del Paraguay es la historia de su lengua guaraní” dice el antropólogo Bartomeu Melià en su libro Mundo Guaraní (2011). La historia del Paraguay es también la de una prohibición que pesa sobre esta lengua, y de la exclusión que supone hablarla. Pero es la historia de una persistencia.

En una escena emergente y cada vez más prolífica del cine en Paraguay, el guaraní de los paraguayos se está haciendo audible a nivel internacional, haciendo visibles sus historias; y se vuelve una cuestión posible. Pero, ¿hablar la lengua guaraní significa ser Guaraní? Quizás ésta constituya una oportunidad para reflexionar en torno a estas ambivalencias, tanto en lo que se refiere al status como a las pertenencias varias del guaraní: el mundo indígena, el campesino paraguayo, y el urbano.

PERO EL GUARANI EN EL CINE TIENE SU HISTORIA; UNA, ACASO, NO TAN RECIENTE

“Las primeras películas en guaraní eran mudas,” me señala el actor y comunicador Manuel Cuenca, autor de Historia del Audiovisual en Paraguay(2009), en el que elabora un recuento de las producciones en el país. Desde principios del siglo XX se había registrado en películas de 35 mm ‒mudas, en blanco y negro‒ comunidades indígenas y campesinas del Paraguay, en las que se conversa o canta en guaraní. Codicia (1954), del director argentino Catrano Catrani, fue la primera película sonora de ficción en incorporar diálogos en guaraní. Basadas en la obra del escritor Augusto Roa Bastos, quien también realizó las adaptaciones a guión, Armando Bó produjo La Sed (1961) y El trueno entre las hojas (1975); en la cual, además de diálogos, se puede escuchar la canción Adiós Lucerito Alba de Eladio Martínez, en guaraní (las escenas de desnudo de Isabel Sarli se hicieron famosas, y ella reapareció en India (1961) y La burrerita de Ypacaraí (1962) de Bó.) La sangre y la semilla (1959) fue la primera co-producción bilingüe paraguayo-argentina. Por su parte, Dominique Dubosc filmó sus primeras obras en Paraguay, a finales de los 60: en clave poética y con las voces de los protagonistas registra la vida de una familia campesina paraguaya y la del leprosorio Santa Isabel en Cuarahy Ohechá (Le soleil l’avu) (1968), y Manojhara (1969).

Aunque traten sobre los Guaraníes o éstos intervengan en las tramas, en muchas películas se ha recurrido a otras comunidades indígenas e inclusive a no-indígenas para representarlos. Para sus películas en las que se hace alusión a los Guaraníes, Bó recurrió a los Maká del Paraguay, que en realidad pertenecen a la familia lingüística Mataco; ya en las primeras escenas de Indiaen las que aparecen se escucha una canción que dice “india Guaraní…”, con Isabel Sarli caracterizada como indígena; paradójicamente, no es difícil encontrar en manuales escolares fotografías de los Maká cuyos pies de foto los sugieren Guaraníes.

Con música de Ennio Morricone, Roland Joffé dirigió The Mission (1986). Robert De Niro y Jeremy Irons protagonizan una historia basada en las legendarias Misiones Jesuíticas del Paraguay. A pesar de mis esfuerzos, no logro reconocer el guaraní de los indígenas que actúan en ella ‒ni siquiera cuando lo habla Irons‒. The Mission no se filmó en Paraguay: las escenas que corresponderían a Asunción se rodaron en Cartagena de Indias, Colombia; una de las locaciones son las Cataratas del Iguaçú en Brasil; y los indígenas no son Guaraníes sino, en gran parte, Waunanas del Chocó colombiano. Pero es posible acortar distancias: líder indígena en Argentina, Asunción Ontiveros interpreta un cacique Guaraní; en el making of titulado Omnibus: The Mission, Ontiveros revela problemas comunes a Waunanas y Guaraníes ‒y acaso a los indígenas en toda América‒: el territorio.

Aunque se llamen igual, hay más de una lengua guaraní; y aun cuando se llamen de otra manera, hay lenguas que son tan guaraní como otras, idénticas a pesar de diferentes. En Hans Staden (1999) de Luis Alberto Pereira los indígenas Tupinambá son interpretados por actores no-indígenas. Basada en las crónicas de Staden y hablada en tupí clásico (de la familia lingüística Tupí-Guaraní), hay en la película una pretensión realista: el director insiste en una suerte de neutralidad desprovista de interpretación (a diferencia de otras películas que abordan la misma historia), pero se basa en un texto previo, un discurso testimonial en sí embebido en interpretación; así, la representación de los indígenas ‒más que de la historia‒ nos arroja la memoria de los blackface del cine estadounidense de principios del siglo XX.

¿No hay actores Guaraníes? Sí los hay: se los puede ver en Terra Vermelha (2009) de Marcos Bechis. Allí es el drama de los Guaraní-Kaiowá (conocidos como Pãi Tavyterã en Paraguay), en la frontera Paraguay/Brasil. Actúan de sí mismos, en su propia lengua, para mostrar la amenaza que el agro-negocio supone para sus modos de ser, en fechas en que el suicidio protagonizado por jóvenes representa un trauma social cada vez más constante. El drama de la ficción es real: el líder Ambrósio Vilhalva (cacique Nádio en la película) interpretó su muerte, y luego fue asesinado, realmente, hace poco más de un año.

Representados por otros, o expuestos por la mirada de otros. Pero quizás esta realidad cambie pronto. Pertenecientes a la misma familia lingüística de los Guaraníes, los Aché han estado rodando. Norma Tapari y Ricardo Mbekrorongi realizaron los documentales Nondjewaregi/Costumbres antiguas (2012) y Tõ Mumbu (2012), respectivamente, en los que recogen testimonios de sus abuelos, en el marco del proyecto Ache djawu/Palabra Aché, que con producción literaria, fotográfica y audiovisual busca un rescate cultural.

EL GUARANI EN EL CINE CONTEMPORÁNEO DE PARAGUAY

¿Es esa mi voz? Como al escucharse por primera vez en una grabación, verse en pantalla, por una vez. Hamaca Paraguaya es la primera película de Paraguay que he visto. La experiencia fue excepcional, acaso porque la película también lo era. Atravesando la historia, se presenta una imagen del tiempo: la idea de una espera/esperanza oscilante y pendular que no cambia de sitio, a pesar de la inestabilidad. Los diálogos circulares están inscriptos en una escena igualmente estructurada por lo circular. En Hamaca… hay un deseo de representar un tiempo paraguayo, que acaso pueda imaginarse en encrucijada con otra memoria temporal, la del oguatáva (caminante) Guaraní, presente en el jeroky ñembo’e(danza/rezo) igualmente circular de los Guaraníes.

El Paraguay atravesaba fechas duras tras la masacre de Curuguaty (el 15 de junio de 2012 durante la ejecución de una supuesta orden de allanamiento, policías se enfrentaron a campesinos sin tierra: el enfrentamiento terminó con la muerte de 17 personas, y fue una de las causales para el golpe de Estado parlamentario, disfrazado de juicio político, que destituyó al entonces presidente Fernando Lugo). Para algunos, ver 7 cajas constituyó una experiencia catártica. Varios meses de salas repletas: cuando me tocó el turno, el fenómeno social hablaba (literalmente) tan fuerte como la película: como el que se escucha por primera vez ‒o como el que se ve‒ eran ahí espectadores bulliciosos, riéndose a carcajadas y aplaudiendo; una sala en ebullición.

Más allá de la historia, del universo representado e imaginado, y de su lenguaje, 7 cajas puede ser leída en clave de metáfora: Acaso no se trate sólo acerca de los únicos mecanismos con los que cuenta el pobre para acceder a una puesta en circulación de su propia imagen en el atiborrado mercado de las imágenes, sino también acerca de las condiciones en las que opera el cineasta paraguayo en una escena de emergencias: el personaje Víctor podría tratarse de un cineasta más en búsqueda de recursos para producir imágenes y hacer en pantalla sus historias, y hacerse en pantalla.

Estas dos son algunas de las películas con guaraní que han alcanzado mayor visibilidad a nivel internacional, pero no son las únicas. Y hay más en camino.

En 2002, Galia Giménez estrenó su María Escobar, basada en una canción homónima en guaraní que por entonces se había vuelto muy popular, trascendiendo estratos sociales. Los cortometrajes Karai Norte (2009) de Marcelo Martinessi y Ahendu Nde Sakupái (2008) de Pablo Lamar son obras maestras del audiovisual paraguayo. Recientemente estrenadas, Latas Vacías (2014) de Hérib Godoy y Costa Dulce (2013) de Enrique Collar giran en torno al pláta-yvyguy (tesoros enterrados durante la guerra en el siglo XIX, sobre los cuales la imaginación de los paraguayos ha versado prolíficamente); ambas están habladas en un guaraní campesino y periférico con relación a la capital Asunción, con actores del interior que no han pasado por las tradicionales escuelas de actuación, aportando una voz fresca al de por sí nuevo cine de Paraguay. Mientras Luna de Cigarras (2014) de Jorge Díaz de Bedoya, en la que el guaraní se muestra en su zona fronteriza con el castellano y el portugués, ha sido nominada a los Premios Goya de España.

Enrique Collar. Costa Dulce. 2013. (Fotograma)

En el género documental el guaraní ha florecido en una lista extensa que va desde el patrimonio audiovisual mudo hasta reconocidas piezas que regitran voces campesinas e indígenas, como Tierra Roja (2006) y Frankfurt (2008) de Ramiro Gómez; o Fuera de Campo (2014) de Hugo Giménez. En Yvyperõme (2013) de Miguel Armoa el testimonio de un chamán guaraní que sugiere que “antes éramos los brujos del bosque, hoy somos los brujos de la soja,” da cuenta de las fechas traumáticas y transformadoras por las que atraviesa el Paraguay.

Estigmas y prohibiciones que han pesado sobre el guaraní lo han puesto en una situación de amenaza, y su tránsito de una generación a otra se ha visto dificultado. ¿No tiene cierta participación en esto el hecho de que los medios hegemónicos de comunicación se hablen y se escriban en castellano y no en guaraní a pesar de que la mayoría de la población sea guaraní-hablante o en cierta medida bilingüe?

En 2015 se estrenará Guaraní, del director argentino Luis Zorraquín que, además de estar hablada casi enteramente en guaraní, versa precisamente sobre la lengua guaraní. La película y los abordajes periodísticos que de ella se han hecho hasta el momento pueden servir para explorar las pertenencias ambivalentes del guaraní hoy: las variantes del guaraní de los Guaraníes y el guaraní de los paraguayos. John Hopewell escribe para la revista Varietysugiriendo que la película trata de cuestiones identitarias y de tradición en una jornada protagonizada por “a tradicionalist Guarani fisherman, and his grand-daughter.” Reproduciendo un cable de la Agencia de Noticias EFE, en ABC Colorde Paraguay se afirma que se trata de “una historia sobre el desarraigo y sobre la sobrevivencia de la cultura indígena guaraní.” Ambas reseñas se equivocan: se trata de la historia de un paraguayo y su resistencia en la lengua en una apuesta de futuro.

Luis Zorraquín. Guaraní. 2015. (Fotograma).

Pero, ¿qué significa el lugar de estas confusiones? La palabra guaraní significa tanto: el nombre de una lengua y el de una cultura; por veces, apodo-gentilicio de los paraguayos; el nombre de tiendas, tés adelgazantes y clubes deportivos.

La persistencia del guaraní en una sociedad más occidental que indígena también es ambivalente: lengua subalterna en Paraguay, parecería incoherente su hegemonía, ahí donde se insiste en rechazar lo indígena con vehemencia. Pero esa “grosería” de resistir se hace cada vez más patente, sorteando la mudez también en el cine, donde el guaraní habla más fuerte. Cada vez.

Spring 2015, Volume XIV, Number 3

Damián Cabrera is a Paraguayan writer. He is a Master’s candidate in Cultural Studies at the University of São Paulo. A participant in the seminar of Critical Cultural Space/Critique (Paraguay), he is a member of the collective Ura Editions and the Network Conceptualismos del Sur. He is the author of the novel Xiru(2012), for which he won the Roque Gaona Prize the same year. He can be reached at guyrapu@gmail.com

Damián Cabrera es escritor, Licenciado en Letras y magíster candidate en Estudios Culturales por la Universidade de São Paulo. Participante del seminario de Crítica Cultural Espacio/Crítica (Paraguay). Integra el colectivo Ediciones de la Ura, y la Red Conceptualismos del Sur. Autor de la novela Xiru (2012), ganador del Premio “Roque Gaona” 2012. guyrapu@gmail.com

Related Articles

Jesuit Reflections on their Overseas Missions

When you think of Jesuits in their missions around the world, you—the casual reader—might not think of Plato or ancient Greek authors. Yet two of these…

Paraguay: Un país en una lengua misteriosa y singular

English + Español

If you arrived in a country where almost 90% of the inhabitants speak Guarani, an official and national language along with Spanish but do not identify themselves as “Indian” or aboriginal…

Territory Guarani: Editor’s Letter

DRCLAS receptions are bustling affairs, sparkling with ample liquor, Latin American tidbits and compelling conversations. It was at one of these receptions that Jorge Silvetti and Graciela Silvestri first approached me casually regarding an issue about the Guarani…