A Review of Guerrilla Marketing: Counterinsurgency and Capitalism in Colombia

Brand Bombing

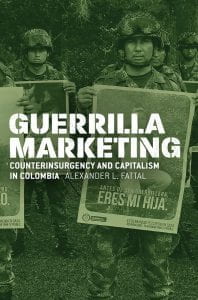

Guerrilla Marketing: Counterinsurgency and Capitalism in Colombia by Alexander L. Fattal University of Chicago Press, 2018, 310 pages

Colombia’s decades-long civil war has waxed and waned over the last fifty years. It has claimed the lives of 220,000 Colombians and displaced five million people from their homes. As the conflict spiraled into a vortex of violence in the 1990s and early 2000s, the U.S. government funneled billions of dollars of aid to the armed forces to wage a counterinsurgent campaign against leftist guerrillas. Human rights organizations blamed state security forces and allied, right-wing paramilitary forces for the majority of extra-judicial executions, massacres, disappearances and massive forced displacement. All this was done with U.S. aid and political support under the guise of a drug war that gave no quarter to the rebels or civilians believed to be allied with them.

The war reorganized Colombian society. Unfortunate members of one of the world’s largest populations of internal refugees, rural migrants created shantytowns, sprouting like mushrooms on urban peripheries. A violent counter-agrarian reform washed over the countryside, consolidating some of the most fertile lands into the hands of paramilitaries and the elites whose interests they served. The repression of labor unions, left-leaning political parties, indigenous and peasant organizations, students, and human rights advocates cleared a path for the enactment of free-market policies, which drove working people into poverty and further fueled the armed struggle.

Yet as the war reached a bloody crescendo in the early 21st century, the Colombian government developed a new message for international audiences critical of its human rights record and war-weary domestic constituents who distrusted the armed forces. The Ministry of Defense began to describe its counterinsurgent crusade as a “humanitarian intervention” and embraced Madison Avenue-style marketing campaigns to sanitize the conflict and encourage guerrillas to demobilize. In his revealing book, Alex Fattal describes how the military’s branding and marketing initiative was more important and successful than scholars and journalists have appreciated. Between 2 003 and 2006, s ome 16,000 Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) insurgents deserted and joined the government’s individual demobilization program, nearly double the number who collectively laid down their weapons after the historic 2017 peace agreement between the government and the guerrillas. The FARC was Colombia’s largest and oldest insurgency. Fattal’s insightful account focuses on the Ministry of Defense’s Program for Humanitarian Attention to the Demobilized (PAHD), an initiative dedicated to demobilizing individual FARC insurgents, remobilizing them as army informants, and cleansing the sanguinary image of the armed forces through clever marketing techniques.

Unlike the Central American civil wars of the 1980s, which ended with peace accords between all warring factions, the Colombian government has pursued separate peace deals with different armed groups but never with all of them at the same time. Previous peace processes with the FARC collapsed in the mid-1980s and again in 2002, while formal talks with another insurgency—the National Liberation Army (ELN)— have yet to materialize, and a partial paramilitary demobilization between 2003 and 2006 was a charade. The far-right paramilitaries were never at war with the state. Amid this history of failed peace processes, demobilization, and remobilization, the PAHD, according to Fattal, represents a government initiative to create a “post-conflict” society amid a civil war that has still not ended, despite the celebrated 2017 peace accords.

In the oxymoronic world of post-conflict Colombia, government funds flow disproportionately to the armed forces , free market policies generate some of Latin America’s highest levels of inequality, and institutions dedicated to health and education are insolvent. Rather than addressing the root causes of the conflict, which are embedded in a long history of economic inequality, political exclusion and lop- sided landholding structures, the government has turned to marketing its campaign against the FARC as “humanitarian counterinsurgency” and developed new, targeted welfare schemes for demobilized insurgents. Fattal argues that guerrilla marketing is “an activist form of camouflage” that seeks to paper over the deep social and political contradictions generated by decades of free-market policies.

He begins the story with a useful chapter onthe history of media spectacle in late 20th-century Colombia. He examines how the M-19 guerrillas, the drug lord Pablo Escobar and the FARC used different strategies to penetrate Colombia’s hostile corporate media environment. Perhaps the most controversial approach was kidnapping, a practice developed most fully by the FARC. The FARC used kidnapping to generate publicity and finance its activities, but the strategy backfired. The guerrillas became pariahs. According to Fattal, even though paramilitary massacres and forced displacements were exploding at the same time as the FARC turned to kidnapping, the insurgents suffered the most severe public condemnation. Outlawed in Colombia and with few international allies, the FARC found itself marginalized from political discourse, which it could not control, and lost the opportunity to claim legitimacy as an opposition political movement. The military, however, developed programs like the PAHD to wrap itself in the cloak of humanitarianism.

Fattal then zooms in on the partnership between the PAHD and an elite consumer marketing firm to explore how military power and marketing became fused in a 2010 holiday initiative dubbed “Operation Christmas.” The propaganda campaign served a dual purpose: it urged the guerrillas to desert by flooding the radio and television with messages designed to exploit insurgents’ emotional vulnerabilities,and it targeted national and international publics with images of a modern military waging tender and compassionate counterinsurgency. The broader effects were insidious: Operation Christmas militarized a holiday that Colombians associate with family and manipulated deeply felt emotions for propagandistic purposes.

These themes are deepened in Fattal’s discussion of the military’s year-long effort to demobilize a key FARC leader and remobilize him as an army informant. Using intelligence about his personal life, manipulating of his relatives, and carefully crafting messages, intelligence operatives succeeded in communicating care and concern for the individual, which led to his desertion. Fattal argues that the military’s ability to take advantage of deeply felt emotions and inject fear into family relations made its counterinsurgency campaign effective, even as the number of combat kills remained more important than demobilization within the institutional culture of the armed forces.

Finally, Fattal turns his attention to the lives of demobilized rebels and their struggles to reintegrate into Colombian society, drawing on fieldwork in a working-class neighborhood on the periphery of a southern city. The neighborhood is one of many such localities where former rebels have settled, after the government nurtured hopes of reuniting with family members, joining the middle class, and enjoying “the good life.” The final goal of demobilization is reintegrating ex-combatants into Colombian society by turning them into business people and consumers. Such an approach seeks to guarantee the separation of the demobilized from socialist notions of the common good, and Fattal notes that the strategy is indicative of the state’s enduring commitment to addressing social problems with market fixes.

It is no surprise that the ex-insurgents almost never become successful entrepreneurs. Few employers want to hire former guerrillas nor are established businesses interested in associating with them. In addition, ex-combatants have few business skills, because most joined the FARC as children. Most concerning, however, is the enduring problem of paramilitarism. Paramilitary mafias control the neighborhood where Fattal conducted research, a community that is similar to many other peripheral urban districts throughout Colombia. The demobilized must negotiate the terms of their new lives with some of the same people who once tried to kill them, and entrepreneurialism mostly leads to cycles of credit and indebtedness with paramilitaries, who routinely kill debtors and suppress any expression of political dissent.As Fattal deftly demonstrates, the demobilization program has been less successful at producing middle-class consumers than manufacturing atomized subjects with few political ties who must struggle every day for their survival. It is no wonder that many former rebels choose to remobilize.

Guerrilla Marketing is a fascinating book that illustrates how the government’s turn to marketing blurred the boundaries between war and peace by penetrating deep into the emotional space of insurgents and their families. It is a well-written account that intersperses analytic chapters with the author’s riveting interviews with FARC insurgents, which offer a view into how the rebels understand what has happened to themand sidesteps PAHD propaganda. The book should be read by anyone trying to understand contemporary Colombian society.

Lesley Gill teaches anthropology at Vanderbilt University. She is the author of A Century of Violence in a Red City: Popular Struggle, Counterinsurgency, and Human Rights in Colombia. (Duke University Press, 2016).

Related Articles

A Review of Aaron Copland in Latin America: Music and Cultural Politics

In Aaron Copland in Latin America: Music and Cultural Politics, Carol Hess provides a nuanced exploration of the Brooklyn-born composer and conductor Aaron Copland (1900–1990), who served as a cultural diplomat in Latin America during multiple tours.

A Review of El populismo en América Latina. La pieza que falta para comprender un fenómeno global

In 1946, during a campaign event in Argentina, then-candidate for president Juan Domingo Perón formulated a slogan, “Braden or Perón,” with which he could effectively discredit his opponents and position himself as a defender of national dignity against a foreign power.

A Review of Born in Blood and Fire

The fourth edition of Born in Blood and Fire is a concise yet comprehensive account of the intriguing history of Latin America and will be followed this year by a fifth edition.