In Search of Miss Esme

Memories and History of the Spanish Civil War

Plaza del Castillo in Pamplona, Spain. “Pamplona, Spain” by Emmanuel Dyan is licensed under CC BY 2.0

As a historian I have never worked on the Spanish Civil War. My concerns were Argentine History and women in Latin America. Yet the Spanish Civil War has been central to my life and that of my family.

The war years left deep scars in all of us, scars that bled profusely as soon as we began to speak about certain topics. Although we lived through two wars, “The War” was the Spanish Civil War, it was everything that had happened to us, including our exile. Any attempt to engage my parents in a conversation about a specific event or decision affecting any or all of us was useless. They just refused to answer my questions or explain what I wanted to understand or simply know.

As my retirement was approaching, I decided to write a long essay or a book about the trials, tribulations and meanderings of my family from the moment the Spanish Civil War began on July 18, 1936. We—my parents, my 8-year-old brother Alberto, my 7-year-old sister, Dorita, and my toddler self—were living in Pamplona, the capital of Navarra. An ultra-conservative province on the western border with France, it was fanatically opposed to the new Republic, born of the municipal elections of April 1931. Its Military Governor, General Emilio Mola was one of the leaders of the July 1936 coup. Having failed to topple the government, they found enough support in several provinces to transform it into a civil war, “a crusade” in the words of General Francisco Franco. Navarra was one of its most reliable strongholds.

My father, who was 41 at the time, was a teacher who loved his profession and had risen to the rank of Inspector of Primary Education recently. A member of Izquierda Republicana (Left Republican Party) he enthusiastically supported the Republican government reforms, especially those in the field of education.

On the morning of Saturday July 18, as three planes flew low over the city, Pamplona was invaded by an army of Falangists and right-wing monarchist militias known as Carlistas. In the afternoon, the Commander of the Guardia Civil who refused to support the coup was assassinated. The following day, General Mola proclaimed Navarra under the State of War; his troops occupied all government buildings and arrests began. My parents decided that my father was not safe and should try to slip into France, which he did, helped by my mother’s brother. He left the afternoon of Tuesday, July 21, but returned the following day by Irún into Basque territory loyal to the Republic.

A few days later, as arrests and killings multiplied and cadavers appeared on the sides of the roads, my mother, my siblings and I were detained for nearly a month. We were released and eventually exchanged for children and adults who were caught by the war vacationing in San Sebastián and wanted to return to Navarra. My mother’s fear subsided only when we reached the Republican zone. We then went to Bilbao where we were reunited with my father who was working with the Basque government.

On September 5, 1936, Mola, by then Commander of the Army of the North, ordered an offensive against the Basque region. His forces took Irún and pushing to the west, entered San Sebastián on the 15th. In March 1937 they began the assault on Bilbao, this time with the support of the German Condor Legion. Dorita still remembers the siren calls as the planes approached and despite her fear, taking Alberto’s hand and following our mother who held me in her arms, all of us running towards the refuge we were assigned, a railroad tunnel near the station. After the destruction of Gernika on April 15, 1937, the Basque government decided to evacuate the children. Some 20,000 children were sent to several countries, among them France, England, Mexico, Belgium and the Soviet Union. My sister, the only one among the three of us who could travel because my brother was mentally retarded and I was too little, left in a group of some 3,000 children that boarded the Sontay for the Soviet Union on June 13, 1937.

Six days later, on June 19, 1937 Franco’s troops entered Bilbao. The day before, my mother, Alberto and I were evacuated to Santander. We left Spain for France before the city fell to Franco’s troops on August 26, 1937. We arrived in St. Nazaire and were sent to a village near Lyon with the support of a teachers union. We lived there for almost a year; no one seemed to speak Spanish, there were no other refugees and mother did not speak a word of French. As she told me once, it was a sad and very solitary time for her. She had no news of Dorita and did not know whether my father was dead or alive. “I cried myself to sleep every night, hoping not to wake up in the morning, but since I did not die during the night, I had to try to live one more day.”

My father also left Spain from Gijón but he returned once again to the Republican zone, this time going to Valencia where the government had moved. By late 1938, he joined the last wave of Spaniards escaping Franco’s troops. This time he left Spain never to return. He crossed the border in Cataluña and was put in a concentration camp by French authorities. We were reunited with him after he was released, but to the despair of my parents, Dorita remained in the Soviet Union. World War II began before she was able to leave, so we waited for her ten long years. She joined us in France in 1948, thanks to the efforts of the Basque government in exile.

We never had the intimate, wrenching conversation I thought we should all have wanted. In time I began to toy with the idea of writing about us to see if I could begin to understand everyone and especially myself. I did not know whether I would write a historical narrative or a personal memoir. The first thing I did was to go to France and visit the place we had lived after my father left the concentration camp and became the co-director of a colony of Spanish refugee children. I knew that it was supported by “cuáqueros” (Quakers) as he said, and that the person in charge was a Miss Esme. My parents did not know whether it was a name or a surname, she was just Miss Esme, and the name of her organization was something like “The Foster Parents.” I remembered that we lived in an enormous estate, that it was called Chateau Le Bridon or so I thought, and that it was on the back road to Le Boucau. When I returned to Bayonne, the center of town had not changed. I even found the Café du Teatre where my father had met for years with other refugees every Sunday, but I could not find the back road to Le Boucau—things had changed too much, too many new streets and too many houses.

I went back on two other trips and failed. I was even told that there had been no colonies in Bayonne. However, I persisted and did find the road, part of the estate wall and a small gate. I also learned that the house had been destroyed and a Youth Center had been built on the grounds as well as houses with gardens.

My search for Miss Esme proved harder. In 2007 I googled both her and the Foster Parent organization without success. There was a “Plan” but no information about the 1930s and neither a Foster Parents Plan founded for Spanish children nor colonies. On one occasion, after giving a lecture at Swarthmore, I went to the Society of Friends Archives in Philadelphia to see if they had any information about Le Bridon and/or Miss Esme but found absolutely nothing. During a three-month teaching visit to University College London, I spent many days in the Quaker Reading Room looking for Miss Esme, again without success. When several books appeared in Spain about the Civil War children and the colonies, once again Le Bridon and Miss Esme were absent.

Quite by chance I met Nancy Clough, who approached me after a panel on children and the civil war at Williams College four years ago. She wanted to write a book about her uncle, Barton Carter, a handsome and charismatic young man who died fighting in Spain at age 23. She generously gave me access to an incredible amount of information and documents, including the solution to the Esme mystery.

Barton’s story belongs to Nancy, but suffice to say that the summer of 1936 the young Williams College student went to Spain where he became involved with an English Aid group headed by the Duchess of Athol, a Conservative MP from Scotland. He drove a truck from Valencia to Madrid, bringing supplies to the capital and returning with children. While in Spain, he met two Englishmen, John Langdon-Davies and Eric Muggeridge, who in April 1937, with the support of the Spanish government, founded an organization which they named the Foster Parents Scheme for Children in Spain. They created colonies for children who were evacuated during the siege of Madrid or other cities, had lost their parents or were separated from them. Barton joined them and shortly after, so did Miss Esme Odgers, a young Australian woman with a radiant smile, member of the Young Communist League. She went to Spain with the Secretary General of the Australian Communist Party, with whom she had an affair. Once there, she left him to work with Barton, Langdon- Davies and Muggeridge. That was not all, Nancy also discovered that the University of Rhode Island held the papers of the Foster Parents Scheme. It had changed its name when WWII began and is presently called Plan. In the summer of 2009, I was able to see my brother’s name and my own on the list of children in the Le Bridon colony.

The real shock was to learn that Miss Esme was a Communist and not a Quaker. I could not believe that my father had made such a mistake. If his information on Miss Esme was so wrong, how could I rely on his memory, my mother’s, Dorita’s or my own? On the other hand, I kept telling myself that if I had not insisted, trusting my memory (and the old pictures I had) when people kept telling me that there was no Le Bridon, I would have never found its traces. So I concluded that the thing to do is to trust my family’s memory, but anchor it in documents, anchor it in history and that is what I am doing.

Marysa Navarro is the Charles and Elfriede Collis Professor of History Emerita at Dartmouth College and Resident Scholar at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies.

Related Articles

Because They Were Taken Alive: Forced Disappearance in Latin America

In Guatemala City, a single garage light has been burning continuously for almost thirty years. The garage’s owner, a woman now in her nineties, cannot bring herself to turn it off. On May 15, 1984, her son, Rubén Amílcar Farfán, left the house early as he usually did, headed for the university. But later that afternoon, friends of his rang the doorbell of the family’s house, anguished, to report the worst …

Democracy, Citizenship and Commemoration in Colombia

Military detachments costumed in the historical uniforms of the patriotic army journeyed on foot, by mule and on horseback on a long journey promoted as the Liberty Route to celebrate Colombia’s bicentennial. The media showed the inhabitants of different towns of the country celebrating the arrival of the marchers, fulfilling their own role in this polemic recreation of the official stories about national independence. …

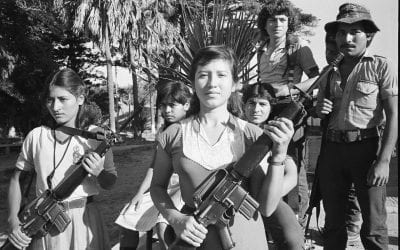

Covering Central America in the 1980s: A Memoir in Words and Photos

The wipers slapped across the rain-smeared windshield as we sped through downtown San Salvador. Nelson Ayala clutched the steering wheel to keep us on the road through the torrential downpour. It was already two hours past dark, and it felt way too late to be out on the streets in this part of town. Suddenly, a body appeared in the headlights just ahead of us, sprawled on the pavement. …