Is Dollarization a Good Idea?

Focus on Argentina

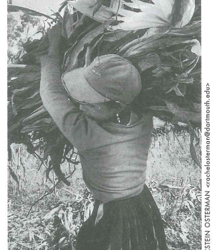

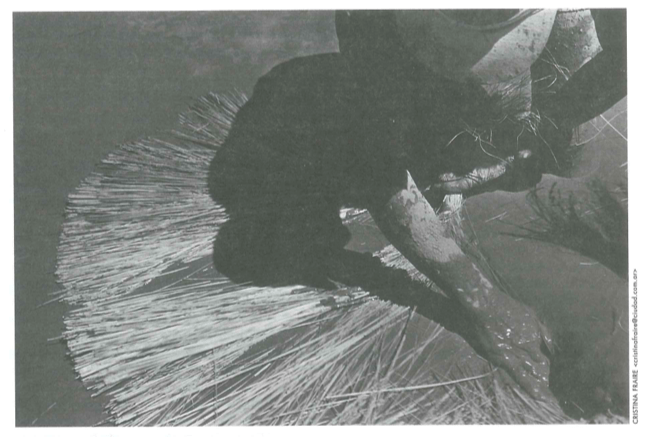

Working in Argentina: preparing straw for a roof.

Argentina’s current economic outlook is bleak. Last spring’s shock to international capital markets which caused a devaluation in Brazil has now combined with uncertainty over the upcoming presidential elections to cause high interest rates, crippling public debt, widespread unemployment, and rising inequality. Neither the Peronist nor the Alliance Party presidential candidate will distance his economic policy from current president Peronist Carlos Menem’s programs of privatization and convertibility. A fiscal rescue will be difficult and a monetary expansion is outlawed. Low labor productivity, an overpriced exchange rate and market uncertainty suggest that the current situation is likely to remain for at least another year and perhaps even longer. Into this situation, the debate over dollarization, the replacement of the Argentine peso with the U.S. dollar as national currency, intensifies.

Argentina has made great strides toward entering the “first world” economically over the last decade. In 1989, inflation reached as high as 200 percent per month! To put this in context, if one sat down for dinner in the summer of ’89, dessert would be more cost more at the end of the meal than at the beginning. Since the Menem regime and Peronist Party took over at the beginning of the decade, large-scale changes have been put in place. Huge, inefficient publicly owned companies have been privatized in an effort to raise large amounts of hard currency. This cash has been used to support the current Convertibility Law, the Menem government’s most proud achievement. Under convertibility, a currency-board-like arrangement is put in place that forces the US dollar to be fully convertible, one to one, with the Argentine peso. Devaluation (equivalent to increasing the supply of money or lowering interest rates by the central bank) is outlawed. Every peso is backed up with a dollar in Argentine reserves and thus there is no threat of “forced devaluation” due to bankruptcy of the central bank. This scheme has reduced inflation to nearly zero and until recently provided the economy with large amounts of cheap capital by reducing the currency risk involved with investment.

However it is clear to several foreign economists that the depth and length of the current Argentine recession is, in part, a result of the convertibility scheme itself. Though it is certainly an unpopular suggestion to contend that convertibility should be dismantled now in favor of a floating exchange rate, the current situation does have clear implications for the long-term viability of the current regime. Though lower than they would be if the peso floated against the dollar, interest rates remain too high for all but the largest firms to have access to borrowed funds and consumers pay extremely high rates for credit. Furthermore, convertibility can be a terrible constraint on the economy. Brazil, via devaluation, is exporting its way out of its recession at the expense of Argentine goods, which are now far too expensive to compete.

Interestingly, the public consciousness is wedded to the middle ground of convertibility. Public opinion is against official dollarization because Argentines have too much pride to use only the US dollar as currency. However there is also a refusal to even consider a floating currency because no one trusts the Argentine peso to hold its value. Indeed most large transactions already take place in dollars.

Let me briefly elaborate on the monetary mechanism as it currently affects Argentina. When faced with a disastrous collapse in competitiveness due to foreign price shocks, like the devaluation in Brazil, a country has two choices. First it can devalue its own currency causing an immediate cut in wages across the board in real terms. This makes exports appear cheaper to foreigners, and increases the money supply. Or a country can go through a long transition period with high unemployment until wages are bargained downward by each individual firm which either manages to lower its costs or goes out of business while trying. This second mechanism is much more severe, and it is exactly the process Argentina is experiencing right now because devaluation is outlawed. Thus convertibility remains mired in a middle ground with both limits on monetary flexibility and high interest rates.

Dollarization has recently been dismissed by many as a publicity ploy of the Menem government to ease investor’s fears of devaluation. However it should be given legitimate consideration as possible long-term solution that would provide lower interest rates. Indeed when Argentine economists, members of the Finance ministry, and bankers are asked, “Is dollarization a good idea?” the answer is generally yes, though they only rarely say that to the public. Though devaluation is outlawed, there is constant fear in bond markets that the government will change the laws. This fear leads to higher interest rates and country risk. Dollarization removes that risk because, once dollarized, Argentina would have a very hard time returning to its own inflationary national currency. Thus when comparing dollarization to the current convertibility law the bankers are correct. Dollarization would cause lower interest rates that would provide cheaper capital, more investment, and more jobs. Almost everyone in the economy would be better off and welfare would be improved. A perceived loss of national identity and pride is easily overcome. If Argentines resent George Washington on their money, they can, like the Panamanians, keeppeso notes while abolishing peso deposits and thus still have a fully dollarized economy. No more national identity is given up under a dollarized regime than under the current convertibility law, except for the possibility of future monetary independence. Thus Dollarization has the same faults as convertibility with some added benefits. It seems Menem just jumped the gun in his rash desire to make bold initiatives as a lame duck in office. The debate should continue.

However it is essential to recognize that Dollarization would still leave the Argentine economy open to long and deep recessions like the one it is experiencing now. A rarely asked question that should be near the center of any Argentine economic debate is “when will the peso be viable on its own?” One answer I have heard repeatedly is, “not now.” Indeed dollarization is only an appropriate long-term solution if the peso will never be viable again. Will the scars from the hyperinflation of the eighties ever heal? It seems as much a question for psychologists as for economists (both of which Argentina has in abundance). But Brazil and Mexico have both allowed their currencies to float and had generally positive results. From my point of view, a flexible exchange rate is the appropriate long-term regime for a country with an economy the size of Argentina. Perhaps more important, one can conclude from the current recession that a long-term link to the dollar would not solve all of Argentina’s problems.

In terms of efficiency, it seems painfully clear that George Soros was right when he said earlier this year that the Argentine peso is overvalued. Great strides in labor productivity are necessary to bring it back into equilibrium. The extremely high rate of unemployment is proof. An over-valued wage makes the market clear through high unemployment as supply of labor vastly outstrips demand. This has left an economy that dreadfully under-uses its labor resources because wage levels are too expensive for businesses to afford. Argentina’s economy will only start growing again when the labor market comes back into balance through lower wages, and higher productivity.

In conclusion, there needs to be a long-term focus to this discussion over currency regime. The dollarization debate must focus not on the immediate benefits, but rather on whether an Argentine peso could ever be viable on its own. In which case the permanence of dollarization would be a drastic misstep. Furthermore the economic discussion must focus on longer term goals of increased employment and equality as means for efficiency and stability instead of solely on GDP growth though the topics are not mutually exclusive. Finally the government should focus on improving economic structures and institutions to create confidence, at which point an Argentine currency could be viable on world markets on its own and dollarization would no longer be a consideration. Though dollarization would provide large immediate benefits in comparison with convertibility, the current recession suggests that neither regime is the appropriate long-term solution.

Fall 1999

Eli Cohen, a Harvard undergraduate in economics, received a 1999 DRCLAS Summer Research Travel Grant Award to examine the costs and benefits of dollarisation to the Argentine economy.

Related Articles

Its Strengths, Problems, and Future

Latin America can take a punch. Its endurance of a whole series of rather large shocks in the last two years is a tribute to the region’s extensive structural reforms. The consequences a decade…

Health and Wealth

The difficulties of operating in a tropical environment were already abundantly clear during the building of the Panama Canal more than a hundred years ago. “The effect of the climate on tools…

Economic Insecurity in Latin America

A 23-year old Brazilian woman was among 10,000 job applicants seeking a desk job at Banco do Brazil. When asked why she was seeking employment that actually paid less than her present…