Latin@ Education and Poverty

A Roundtable Discussion

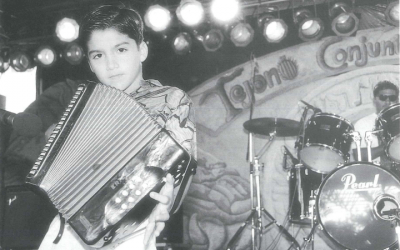

Students proudly show their work in a Riverside, California, School. Photo by Nathalia Jaramillo.

Maria E. Barajas, once a Mexican immigrant child placed in remedial classes because of her “language problems,” has focused her interest in bilingual policy through Harvard Graduate School of Education’s International Education Policy program. “The IEP program allows me to conduct in-depth research on issues of power and ideology and how these elements connect or collide to form policy and pedagogy,” she observes.

Nereyda Salinas, a Masters in Public Policy student at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, was born on the south side of Chicago to Mexican immigrants. She attended a Catholic grammar school in her community and a public magnet high school on the other side of Chicago, eventually graduating from Stanford University in International Relations. She worked two years in a Chicago based nonprofit, advising schools on leadership development and school reform before coming to Harvard.

Victor Pérez, a Mexican-American from Los Angeles and a graduate of the University of Southern California, is a Masters candidate in the administration, economy and social policy program in the Harvard Graduate School of Education. He is particularly interested in Latin@ politics, especially those issues related to California and stratification, inequality and schooling in higher education.

Nathalia Jaramillo, who began teaching elementary school in Riverside, California three years ago, found that the realities of teaching in a “barrio” with predominantly Mexican immigrant children quickly opened her eyes to the realities of social inequality in schooling. At Harvard’s International Education Policy Program (IEP), her interests have remained in civil rights with a distinct emphasis on Latin@s in California. The IEP program attracts both students interested in international issues and students interested in reform in the United States.

Manuel Carballo from Costa Rica is also in Harvard Graduate School of Education’s IEP Program; he hopes to go back and work with the issues of inequality in education and marginalized people, as well as peace issues. He has lived in Colombia and the Dominican Republic, as well as a short stay in Japan. He came to the United States six years ago to attend Swarthmore College and stayed on after graduation as a college admissions counselor.

Stacy Edwards from Trinidad and Tobago, the mother of a two-year-old son, was a free-lance television producer for programs on the history and culture of the Caribbean islands before coming to the Harvard Graduate School of Education. She is currently studying International Education with a particular interest in poverty and equality issues in education for the Caribbean region. She plans to return to Trinidad upon graduation and work for a local NGO that is heavily involved in community education (Servol).

What these students have in common is a passion for the issues of education and poverty that grows out of their own personal experience. The students were chosen by Fernando Reimers, Associate Professor of Education at the Graduate School of Education, to participate in a roundtable on Latin@s, poverty, and education in late February. The following are excerpts from the tape-recorded conversation.

DRCLAS: From your point of view, what are the two most important challenges facing Latin@ Education in the year 2000?

Stacy: I think the issue of equality, equality of education, is one that Latin@s face here, as they do in their own countries. The lack of equality is tied not only to poverty, but to politics and to not having much of a voice. It’s also tied to race, which becomes more dynamic in the US perhaps than in Latin America itself. My perspective is a Caribbean one, sort of marginalized. Latin@s are not seeing their culture reflected in the education they receive, either through monolingual programs, or monocultural programs.

DRCLAS: What do you mean by politics?

Stacy: What I mean by politics is that it’s only recently that immigrant groups are getting a voice. And I think because their voice is small, their issues aren’t being effectively addressed. I think their voice is small because they’re visitors in someone else’s land. Despite their numbers, I think their voices are so small because many of them speak a different language and that’s a significant barrier. If you’re either a different race or you speak a different language, it’s hard for you to have a big voice.

My family at home is somewhat middle class, but I remember coming to the States and my father instilling this fear about going through immigration and that I shouldn’t ask any questions, just be very quiet, and don’t say anything that may sort of get me any sort of trouble. Immigrants sort of have this slight fear of the United States: just go there and be very quiet, and get everything you can, and work really hard, and go to school and make money, or whatever, but try not to disrupt the system because it’s not really yours.

I live in a depressed part of Dorchester, and I see kids, mostly black and Latin@s, with this hopelessness about them. I think part of it is because they are pushed out. I don’t think they’re getting the same quality of education, the same physical conditions that suburban kids are getting. I have my brother-in-law who is thirteen–there is a big age difference between my husband and my brother in law–and he goes to this mediocre middle school: it’s not enough. I don’t feel that extra push.

Manuel: I think part of it is getting to a place that is foreign to you and for the first time feeling like an outsider. In a sense it is what Stacy was saying, wanting to be in your own life and not really participating, but in another sense, it’s also not knowing what to expect if you are treated cruelly every time you go out to the store. You didn’t grow up knowing you were any different, that’s the experience you’d had since you’ve been in the U.S. You don’t know that you can fight, that you can protest. There is also the sense of fear with illegal immigrants, of not wanting to make too much noise.

So that’s what I wanted to say about the lack of voice. And there is also the other thing that I noticed. The big difference between the black movement and the Latin@ movement is the fact, that we all have to deal with the fact that we’re all so diverse. With the Black movement there is the diversity, but it goes back a lot longer, and there is the common history of struggle. The Latin@ immigration, though, is a little more recent and all of a sudden Costa Ricans, Cubans, and Argentinians, are all put in the same category, expected to get together and express one same voice. It is hard for many of us at first to relate our life commonalities I think there is more that keeps us together than pulls us apart, but it’s hard at times to come out of that with one voice.

Victor: I think it’s different for communities. I’m particularly interested in California because I’m from there. And with the recent immigration policies that have come up, for example, 187, which created an intense and a highly number of immigrants applying for naturalization and citizens. I think there will be a new voice because these new immigrants are now becoming citizens, I think that politics will be impacted positively.

Maria: Right now there are a lot of academics very interested in Latin@s, especially in the US. They are making a lot of decisions about Latin@ voices, maybe doing a little survey or something, and it’s probably totally contrived in saying, “this is what Latin@s think.” I think that’s really scary as well. I think that if Latin@s don’t rise up and say their voice, someone else is going to say it for them.

I’ve seen when they’re asking the wrong population, upper or middle class Latin@s who don’t have kids, or don’t have children in bilingual education and how they feel about that sort of thing. Or they’re asking questions like: “if you were to have the choice between giving your child bilingual English if it would hurt their English, would you do it?” No, of course not. I don’t want my kid to hurt their English. Things like that, and so, see they don’t want bilingual education, but it’s not the right question. And that particular survey is a big survey that is used in terms of support against shutting down bilingual education.

Maria: I was able to read as a child only because of the tenacity of my mother, who used our limited resources to buy second-hand books which she read to my sisters and I until the bindings broke and the words faded and tore. I worked hard to catch-up in all the other academic subjects, however, I never forgot this early experience and the injustice of a system that let me, my sisters and every Mexican-immigrant child in our local school district fall through the cracks.

I’m now really interested in the area of education reform and getting more students into college, more disadvantaged students into secondary education. I think an important challenge is organizing ourselves. In terms of education, there is this mentality of a lot of short term gratification and that has to change if we are going to. If you want to get somewhere in this country and you don’t have anything, you can’t be into short term gratification because education doesn’t work on a short term gratification level. I think education is the only way that Latin@s are every going to get anywhere in this country. You have to learn the language, you have to learn how society works, and the only way you’re going to do that is through entering into the educational system And it has to be quality educational system.

Whether we like test scoring or not, we’re going to have to deal with that, and we’re going to have to get our kids to really learn how to take tests. If we want to make our schools supplement that, that’s fine; I think everybody in this room has their idea of what real learning is, but let’s make sure that our schools offer both. And that’s where the organizing comes in again. Making sure that there are teachers that have high expectations of our students in those classrooms.

Nathalia: Teaching really is a calling. It’s a 14, 15, 16 hour day, especially when you’re working in a low income neighborhood where the resources are so limited. There’s so much accountability that you’re held to, and your principal isn’t the best, and other teachers often aren’t that great. You see all these policies implemented that you know will only serve to the detriment of your kids. You’re forced to put a little thing on the overhead and start training children to just fill in bubbles for multiple choice exams when you want to expand their minds and you want them to be creative and you want them to be independent thinkers and instead you’re training them to just sit there and fill in bubbles. It’s very frustrating and it’s really hard on your person, and what you hope for.

Nereyda: A cultural shift is also necessary. My parents always said we’re going to go back to Mexico. Finally, when I was in eighth grade and their oldest child was in college, they were like “oh, maybe we should stay here.” We must decide that we are really here. A lot of friends of mine observe that this mentality is very prevalent among Latin@s, especially among Mexican Americans, because Mexico is so close. This is home. If you want to keep your ties with Mexico, that’s fine, and if you want to identify with both cultures, that’s fine, but this is where you have to build your community and you have to change your community, and you have to feel entitled to what you see other people having around there.

We’re becoming a very powerful political force, if we use it, like Victor was mentioning, but we have to realize how to use that clout. We’re also becoming a very important marketing force; because of the short term gratification mentality, and because of our numbers too, we buy a lot of stuff. Coca Cola loves to air our family commercials and our family values, let’s see if they can donate, if they can donate a couple hundred thousand dollars to our community school.

Stacy: Nereyda spoke about the need to sort of see the US as home and to build a community here. That’s very difficult to do when you don’t feel accepted or when you feel like a visitor. It’s kind of something I’m going through because we’re thinking of moving back home. You want to stay here and you want to see this as home and you want to build a community here, but you’re constantly being told that this is not your home and you sort of don’t belong. And then it’s also a thin line I think in building a community and becoming segregated, as I think Victor was saying. It’s a very tricky thing and it’s difficult for immigrants to do.

Nereyda: It is difficult. But, Stacy, you have the option of maybe going back. I guess what gets me, is that if my parents had gone back to Mexico, I would have grown up in a small town with a population of a thousand people, there’s no secondary education in the town. I think that’s part of what kept them here. And you’re right, I think you have to grow some real thick skin if you are going to stay here. Absolutely. My parents first moved to south Chicago when it was a predominantly Polish-American community and these people had created their own community and their own Catholic church. My mother, she’s always been a devote Catholic, and she used to take us to church and sit in a pew with her three children and people around her would move if they were two pews away, they’d move to the other side of the church.

Nathalia: I’ve pretty much focused on K through 12 education, specifically in California. One of the most important challenges I see is the testing movement, and standards and accountability the key words for the year 2000. I think it can be really detrimental to the Latin@ community, specifically the Latin@ community that is in poverty. Latin@s are already overrepresented in dropout rates, and the repercussions of testing are drastic. In California, there is the whole retention movement. You know, Latin@s students that don’t measure up to par can be retained in elementary school. That in itself can lead to higher drop out rates, and I worry.

Manuel: I worked for admissions for a year and a half. And I saw a lot of the problems, in terms of not getting enough applicants to even come to the schools. I got to visit a lot of the schools across the country, and definitely you see the problem with the quality of the schooling. The quality is very different. The schools that have already succeeded–schools with a large Latin@ population–are schools that really had the leaders, people who encourage them to go out and apply to schools all over the place, and then really followed up on the students.

There’s also the problem of those who get in and then totally failing. Part of it was adjusting, getting to a place where you don’t see anyone else like yourself, where the professors are not like you.

Stacy: I think, aside from providing role models, I’d like to think it would affect teacher expectations, I’d like to think that if you have a Latin@ teacher, if you have a African-American teacher, that they will have higher expectations of all of their students, especially those of color. That affects student performance and how students see themselves as well.

Victor: Another element is exposure. I know that I’ve worked in LA Unified school district as a consultant. I remember walking into a school in east Los Angeles, where the population was almost 100% Latin@ and the teacher and administration population was over 75% white. So me coming in, and actually exposing myself, and wearing a tie, and looking different, talking to them about what I’m doing, it was just amazing at the response that I got. All the teachers were telling me, oh I want you to come to my class, speak to my kids. That’s where we begin to see the need and also the ability to have transformative practices.

I’m a product of LA unified and I’m proud to say that I come out of the 100 worst schools of Los Angeles which to anybody here at Harvard, would be like, wow, so what did you do different? I think that along the way, there were people that shared with me certain insights that are not going to be in the textbooks: this is how you apply to college, these are the certain steps you need to take, and that’s also a part of exposure. I think that I and other Latin@s here at Harvard that have come out of LA unified–now that we’re making it through–we also have the responsibility to go back and have these experiences be transformed into our communities.

Maria E Barajas, once a Mexican immigrant child placed in remedial classes because of her “language problems,” has focused her interest in bilingual policy through Harvard Graduate School of Education’s International Education Policy (IEP) program. “The IEP program allows me to conduct in-depth research on issues of power and ideology and how these elements connect or collide to form policy and pedagogy,” she observes.

Neredya Salinas, a Masters in Public Policy student at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, was born on the South Side of Chicago to Mexican immigrants. She attended a Catholic grammar school in her community and a public magnet high school on the other side of Chicago, eventually graduating from Stanford University in International Relations. She worked two years in a Chicago-based nonprofit, advising schools on leadership development and school reform before coming to Harvard.

Victor Pérez, a Mexican-American from Los Angeles and a graduate of the University of Southern California, is a masters candidate in the Administration, Economy, and Social Policy program in the Harvard Graduate School of Education. His is particularly interested in Latin@ politics, especially those issues related to California and stratification, inequality and schooling in higher education.

Nathalia Jaramillo, who began teaching elementary school in Riverside, California, three years ago, found that the realities of teaching in a “barrio” with predominantly Mexican immigrant children quickly opened her eyes to the realities of social inequality in schooling. At Harvard’s International Education Policy Program, her interests have remained in civil rights with a distinct emphasis on Latin@s in California. The IEP program attracts both students interested in international issues and students interested in reform in the United States

Manuel Carballo from Costa Rica is also in Harvard Graduate School of Education’s IEP program; he hopes to go back and work with the issues of inequality in education and marginalized people, as well as peace issues. He has lived in Colombia and the Dominican Republic as well as a short stay in Japan. He came to the United States six years ago to attend Swarthmore College and stayed on after graduation as a college admissions counselor.

Stacy Edwards from Trinidad and Tobago, the mother of a two-year-old son, was a free-lance television producer for programs on the history and culture of the Caribbean islands before coming to the Harvard Graduate School of Education. She is currently studying International Education with a particular interest In poverty and equality issues in education for the Caribbean region. She plans to return to Trinidad upon graduation and work for a local NGO (Servol) that is heavily involved in community education.

Related Articles

Forum on U.S. Hispanics in Madrid

The Trans-Atlantic Project, an academic initiative to study the cultural interactions between Europe, the U.S. and Latin America has been invited by Casa de América, Madrid, to present a …

Cuba Study Tour

Waiting at José Marti International Airport for the first Harvard students to arrive for January’s DRCLAS Cuba Study Tour, my companion, a theater critic at Casa de las Américas, commented to me …

The Soulfulness of Black and Brown Folk

And so, by faithful chance, the negro folksong – the rhythmic cry of the slave – stands to-day not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience …