Leaving No One Behind in the Time of Covid-19

Protests From Argentina to the United States and Beyond

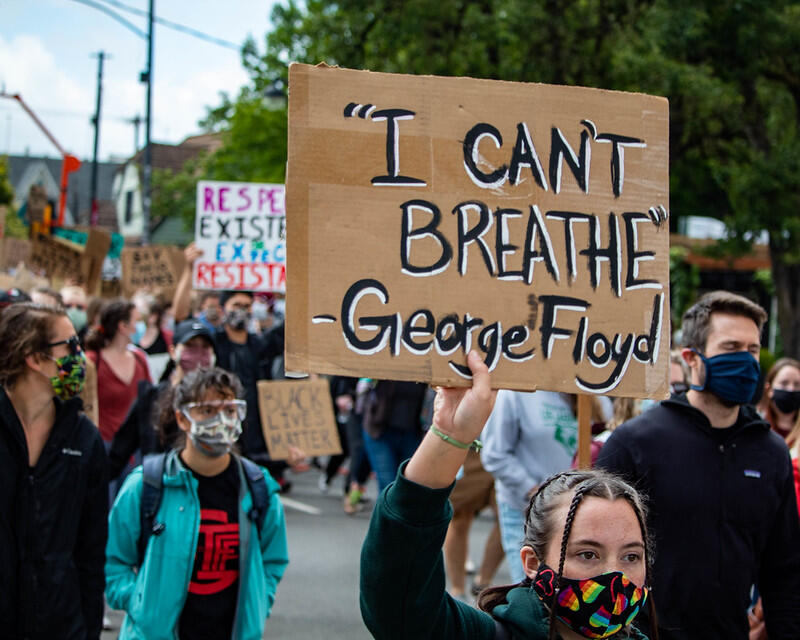

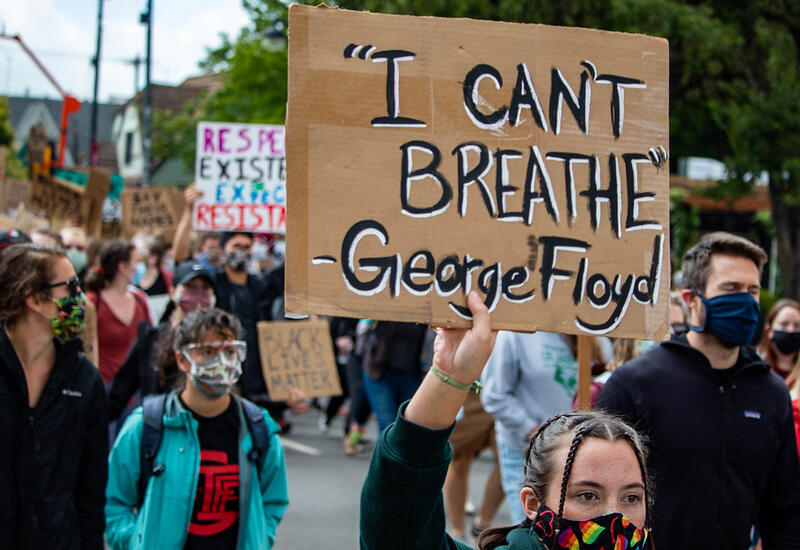

A large group gathered to protest the death of George Floyd at the Wayne Morse Free Speech Plaza in Eugene, Oregon. Photo by David Geitgey Sierralupe

A large group gathered to protest the death of George Floyd at the Wayne Morse Free Speech Plaza in Eugene, Oregon. Photo by David Geitgey Sierralupe

When George Floyd was killed, he had Covid-19. An unarmed African American man had a greater chance of dying at the hands of the police than of dying of Covid-19. That’s even taking into consideration that African Americans already die at a greater rate from the disease was already higher than white or even Latino men.

His murder was not the first case of police abuse that ended in the death of an African American citizen in the United States. Nor was it the first time protests there have swelled in response to the abuse.

Like protests in Latin America, these are the outcomes of a long sequence of unsatisfied demands, but they share three particular features. First, they highlight the fact that the crisis of Covid-19 has worsened the situation of vulnerable population. This is not only the result of economic issues or the lack of access to health care, but because of the relationship that these sectors has with the state.

Second, these protests can be understood through the lens of the expanding wave of conflicts across the continent. In Puerto Rico, the population rose up in July 2019 in reaction to corruption and the mistreatment of the population general and of the hurricane victims. In October of the same year, in Ecuador, the social conflict was sparked by the increase in gasoline prices in the context of belt-tightening structural adjustment policies. The elections in Bolivia led to the mobilization of different sectors of the population who reacted to charges of fraud or, in other cases, to the replacement of the outgoing president before holding elections. A few days later, a series of explosive and unexpected protests erupted in Chile, without a doubt, one of the most important in the country’s history, initially because of the increase in the cost of public transportation and then, as in other countries, extending to other issues and setting off large mobilizations.

Although in each case protests were triggered for different reasons, they have merged a number of heterogeneous demands in a complex fashion, demands that more generally denounce the ruling class and the lack of response to citizen needs by the state.

Third, the huge size of the protests and their leaderless and spontaneous organization, coupled with the fact that the protests for the most part are not led by political figures or social institutions, such as unions or political parties, present challenges to the state for the channeling of their demands.

The protests in the United States and Latin America are both expression of the effect that poverty and racism has on marginalized and vullnerable populations. The health emergency sparked by the pandemic and the enormous economic consequences of the general financial collapse, a byproduct of “non-pharmacological” measures—such as school and business closures and quarantines—, does not affect all groups the same. Undoubtedly , those most affected are people who have less possibility of staying at home, those who lack access to running water to meet basic sanitary standards, the informal workers who get no income unless they work, children from low-income neighborhoods who go to schools that have fewer tools for online learning; women have much longer days when along with working from home they also take care of both household duties and their children; the disadvantaged, when they have formal jobs, work in riskier occupations in jobs other people do not want to do, or they expose themselves to contagion by using public transit to get to work because they do not have cars, Covid-19 survivors who receive huge hospital bills, among other examples.

Undoubtedly, this situation occurs because states fail to respond to these necessities and to achieve levels of social integration for these sectors. Thus, the crisis of Covid-19 makes apparent what Argentine political scientist Guillermo O’Donnell calls the uneven reach of the state, evidenced through its policies and the rule of law. Moreover, the other side of the coin of the absence of guarantees of rights is the presence of the reproduction of segregation, discrimination and/or violence. It is a clear illustration of the idea of institutional violence. Originally, the term referred only to abuses by security forces, but today it is understood in a broader sense as the systematic deprivation of rights in regards to certain groups. The sum of social, economic and educational deficiencies in the African American groups in the United States, as well as other marginalized groups in Latin America—among whom are immigrants from neighboring countries, indigenous peoples and Afro-descendants—are made visible through the crisis of Covid-19, marking the lack of state response towards these communities.

Another characteristic of this new wave of protests is the generalized repudiation of the political elite, independently of the specific demands. Although the protests arising in June 2020 in different countries have as a clear demand the condemnation of racial discrimination, its reach extends and other demands arise.

One of the characteristics of these protests is their theatrical nature and staging through distinct actions such as the demands for women’s rights illustrated by the song “A Rapist in Your Path” (“Un violador en tu camino”) by the Chilean collective “Las Tesis.”. Their music and choreography was repeated over and over again during protests in countries throughout the world, with thousands of women making the denunciations their own.

The multiplicity of demands are the third factor related to the previous one, the spontaneous and largely unorganized nature of the protests. The new technologies have made the cost of organizing protests very inexpensive. Many of these protests are organized and publicized through social media. Two important antecedents for the effective use of social media were the massive protests that took place in 2015 with the hashtag #blacklivematters that began in the United States and the feminist protests that began in Argentina with the hashtag #niunamenos. Both extended to other countries. They lasted for a time as frames for actions, protests and demands on the state, and were effective in making the demands visible to achieve the empathy of sectors that had not previously been empathetic to them. Many times, party-led mobilization of social protest are not seen favorably in the sense that people may be, in way or another, pushed or used in the benefit of some organization or another. However, the spontaneous protests have other problems such as the absence of a spokesperson to negotiate the replies by the state to the demands. The lack of clear leaders in the protests also may result in that radicalized protesters who act violently have no a party or organization to moderate them. These acts of violence can sometimes be fostered by infiltrators, which parties and organizations are aware to control—or at least to try to. The infiltrators seek to increase the level of violence in the protests to scare off more peaceful groups and reduce participation in the protests and support on its demands.

Social protest carry an inherent tension. They are a regular tool of democratic life, in the sense of channelling demands between elections and that emerge outside organized groups that allow governments to be responsive to the new or unanswered demands of the population’s and respond to them with substantive measures. At he same time, to be effective, protests should be disruptive,in a way or in other, as the tango says, el tango “el qué no llora no mama,” which translates loosely as the English expression, “the squeaky wheel gets the grease.” The contemporary leaderless, spontaneous and multiple protests associated with the new technology are caught up in this tension.

In Latin America, the regular protests fulfill different roles, they are a form of relating to the state in their demand for resources, like in other parts of the world, and at the same time can be a tool to demand that the state guarantee civil rights. In the United States, the movement for civil rights and its most recent expressions such as Black Lives Matter demonstrate a similar panorama. In the context of Covid-19, the demands for civil rights by the African American population crosses the visibilization of the neglect of basic social rights for groups whose situation has been worsened even more by the economic consequences of the pandemic. Thus, the protests in the United States converge with the historic demands for social and economic inclusion that are signaled on a regular basis in Latin America through street protests. It is the responsibility of governments to echo protest demands and not leave anyone behind.

Las Protestas de Excluidos en Tiempos de Covid-19

Por Lorena Moscovich

Manifestación por la muerte de George Floyd en Eugene, Oregon. Foto por David Geitgey Sierralupe

Manifestación por la muerte de George Floyd en Eugene, Oregon. Foto por David Geitgey Sierralupe

Al momento de su asesinato George Floyd tenia Covid-19. El riesgo de que un hombre afroamericano y desarmado muera en manos de la policia en este caso fue mas alto que el de morir de Covid-19, y este riesgo, a su vez, ya es mas alto del que corre un hombre blanco o incluso latino.

Su asesinato no es el primer caso de abuso policial en los Estados Unidos que termina con la muerte de un ciudadano afroamericano. Tampoco lo son las protestas que surgieron en reacción al mismo.

Como las protestas en América Latina, estas son manifestación de una larga sucesión demandas insatisfechas, pero tienen tres cuestiones singulares. Primero, lograron visibilizar el hecho de que la vulnerabilidad de muchos sectores de la población se vio seriamente agravada por la crisis de Covid-19. Esta no solo se debe a cuestiones económicas o de falta de acceso a la salud, es principalmente la manifestación de una forma de relación de estos sectores con el estado.

Segundo, estas protestas pueden entenderse bajo el prisma de la amplia ola de conflictos del continente. En Puerto Rico la población se rebeló en julio de 2019 en reacción a la corrupción, y al destrato de la población y de las victimas del huracán. En Octubre del mismo año, en Ecuador el conflicto social se desató una medida que afectaba el precio de los combustibles en el marco de varias políticas de ajuste. Las elecciones en Bolivia motivaron movilizaciones de sectores que reaccionaron ante la denuncias de fraude y otros en reacción al reemplazo del Presidente saliente sin mediar elecciones. Pocos días después, en Chile se sucedió una inesperada y explosiva serie de protestas, las que sin duda serán de las mas importantes de su historia, originalmente en reacción por un aumento en el transporte aunque, como las de los otros países, pronto trascendieron el reclamo original que disparó la movilización.

Aunque en cada país los desencadenantes han sido diferentes, en todos los casos las protestas han catalizado de modo complejo un gran número de demandas heterogéneas de grandes sectores de la población vulnerable y marginada, que cuestionan a la elite dirigente y a la falta de respuesta del estado a sus necesidades.

Tercero, la escala de la protesta y su organización espontanea e inorgánica. Inorganicas en el sentido de que no surgen ni son principalmente lideradas por actores políticos o sociales institucionalizados, como partidos o sindicados, no tienen una cabeza o líder visibles, lo que presenta desafíos para la canalización de sus demandas por parte del estado.

La primera de las continuidades entre las protestas en Estados Unidos y en América Latina se relaciona, entonces, con las poblaciones marginadas y vulneradas,por la pobreza y el racismo. La emergencia sanitaria provocada por la pandemia y las enormes consecuencias de la caída general de la economía, producto también de las medidas “no farmacológicas”—como cierres de escuelas, negocios o cuarentenas—no afectan a todos los grupos por igual. Sin duda, los que están atrás se han visto más seriamente afectados: las personas que viven hacinadas tienen menos posibilidad de quedarse en su casa, aquellos que no tienen acceso al agua no podrán mantener medidas sanitarias básicas, los empleados informales dejarán de percibir sus ingresos si no trabajan, los niños que van a escuelas de menores recursos tendrán menos herramientas para tener clases a distancia, las mujeres tendrán jornadas laborales más extensas entre el trabajo remoto, y el cuidado del hogar y de los hijos, los desventajados, cuando acceden a empleos formales, lo hacen en ocupaciones más riesgosas que otros no quieren hacer, o se exponen en el transporte público a los contagios porque carecen de automóviles. Los sobrevivientes del Covid-19 reciben abultadas cuentas de los establecimientos donde estuvieron internados que no podrán pagar. Y hay mas y mas ejemplos.

Sin lugar a dudas, esta situación emerge por la fallas del estado en responder a estas necesidades y lograr niveles integración social para estos sectores. Así la crisis de Covid-19 pone de manifiesto lo que polítologo Guillermo O’Donnell llama el alcance irregular del estado, a través de sus políticas y del imperio de la ley. Más aún, la contracara de la ausencia para la garantía de los derechos es su presencia en la reproducción de formas de segregación, discriminación y/o violencia. Es ilustrativa al respecto la idea de violencia institucional. Originalmente el termino se refería abuso de las fuerzas de seguridad, hoy también se entiende en un sentido más amplio, como la negación sistemática de derechos respecto de grupos particulares. El conjunto de carencias sociales, económicas y educativas de la población afroamericana en los Estados Unidos y de otros grupos excluidos en América Latina, entre los que también son especialmente afectados los inmigrantes de países limítrofes, los pueblos originarios y los afrodescendientes, puestas de manifiesto con la crisis del Covid-19 son producto de dicha falta de respuesta estatal.

Otra característica de esta nueva ola de protestas es la denuncia generalizada de las elites políticas, con independencia de las demandas puntuales. Aunque las protestas surgidas en junio de 2020 en distintos países tienen como clara demanda la denuncia de la discriminación racial, su alcance se extiende.

Otra de las características de estas protestas es la teatralidad y puesta en escena a través de distintas acciones como la demandas de genero ilustrada por la canción “Un violador en tu camino” del colectivo “Las Tesis” en Chile. Su coreografía fue replicada en diferentes ciudades del mundo por miles de mujeres que se hicieron propia su denuncia.

La multiplicidad de demandas lleva al tercer tema relacionado con el anterior, la inorganicidad de las protestas. Las nuevas tecnologías hace que el costo de organización de las protestas sea muy bajo. Muchas de estas se organizan y difunden redes sociales. Así los ciudadanos salen a las calles presciendo de la coordinación de organizaciones como partidos o sindicatos. Dos importantes antecedentes en este sentido fueron las masivas protestas que se dieron en 2015 bajo el hashtag #blacklivematters que comenzó en los Estados Unidos y el feminista que comenzó en Argentina bajo el hashtag #niunamenos. Ambos se extendieron a otros países, duraron en el tiempo como articuladores de acciones, protestas y demandas al estado, y fueron efectivos en llamar la atención de y visibilizar estas demandas entre para sectores que previamente no empatizaban con las mismas.

Muchas veces, la movilización partidaria de la protesta social es mal vista en el sentido de que las personas son, de un modo u otro, empujadas o usadas para los fines de una organización.Sin embargo, las protestas espontaneas tienen otros problemas, como la ausencia de un interlocutor para el gobierno con el fin de negociar la respuestas a las demandas. La inorganicidad resulta en que en ocasiones sugen actos de violencia evitables porque no hay un liderazgo para moderar a los manifestantes radicalizados. Estos actos de violencia también pueden venir de la participación de infiltrados, partidos y organizaciones conocen de este riesgo y suelen—intentar—evitarlo. Los infiltrados buscan aumentar el nivel de violencia de las protestas para así ahuyentar a los grupos más pacíficos. Cuando esto sucede los participantes espontáneos y moderados reducen su participación y apoyo, y, como resultado, la protesta también pierde su fuerza y sus demandas pierden legitimidad

Las protestas sociales son portadoras de una tensión intrínseca. Por un lado son una herramienta regular de la vida democrática, en el sentido de ayudar a vehiculizar demandas en periodos no electorales y por fuera de los grupos organizados, que permiten que los gobiernos sean receptivos a las nuevas demandas de la población y respondan a estas con acciones concretas. Al mismo tiempo, las protestas deben ser de un modo u otro disruptivas pues como versa el tango “el qué no llora no mama”. En esta tensión se mueven las protestas contemporáneas, inorgánicas, múltiples y facilitadas por las nuevas tecnologías.

En América Latina, las protestas regulares cumplen roles diferentes, son una forma de relación con el estado en la demanda de recursos y, como en otros lugares del mundo, también pueden ser una herramienta para demandar que el estado garantice los derechos civiles. En los Estados Unidos, el movimiento por los derechos civiles y sus expresiones más recientes, como Black Lives Matter muestran un panorama similar. En el contexto del Covid-19, las demandas por estos derechos civiles de la población afroamericana convergen con la puesta de manifiesto de la desatención de derechos sociales básicos de grupos cuya situación se va a ver todavía mas deteriorada por las consecuencias económicas de la pandemia. Así las protestas en Estados Unidos se suman a las demandas históricas por la inclusión social y económica que en América Latina se manifestan regularmente gracias la acción en las calles. Es responsabilidad de los gobiernos hacerse eco de estas para no dejar a nadie a atrás.

Related Articles

A Review of Cuban Privilege: the Making of Immigrant Inequality in America by Susan Eckstein

If anyone had any doubts that Cubans were treated exceptionally well by the United States immigration and welfare authorities, relative to other immigrant groups and even relative to …

A Review of Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle

James Loxton’s Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle makes very important, original contributions to the study of…

Endnote – Eyes on COVID-19

Endnote A Continuing SagaIt’s not over yet. Covid (we’ll drop the -19 going forward) is still causing deaths and serious illness in Latin America and the Caribbean, as elsewhere. One out of every four Covid deaths in the world has taken place in Latin America,...