Living off Trash in Latin America

Debunking the Myths

As a child growing up in Mexico, I often saw men, women, children and the elderly picking through other people’s trash, searching for reusable and recyclable items. Due to their daily contact with garbage, ragged appearance, and often low educational levels, scavengers were considered the poorest of the poor and the lowest of the low in Mexican society. Most Latin American societies have traditionally viewed their own scavengers similarly. Only the poorest and most desperate would be willing to handle trash and sometimes live next to garbage dumps, in order to survive. Scavengers can be found in most cities in the developing world. Yet they are largely ignored by researchers, policy makers and society in general. My experience researching scavengers over the past 15 years may serve to debunk some commonly held beliefs about this population and their activities. My findings may surprise you.

WHY STUDY SCAVENGERS?

When I had to make a decision about the topic of my doctoral dissertation, I thought cross-border scavenging could be an interesting topic. While an undergraduate student in northern Mexico, I sometimes visited Texas border towns and noticed that Mexicans would pick through the trash there. When I searched through the literature on this subject, I was surprised and excited to learn there were only a few scholarly writings about scavengers. I could not find a single publication in the literature—either in Spanish or English—about cross-border recycling on the U.S.-Mexico border.

I was intrigued by the subject as scavenging is relevant to poverty issues, social justice, history, public health, environmental sustainability, industrial development, globalization and climate change.

During my library research I found three highly recommended books: Hector Castillo’s La Sociedad de la Basura: Caciquismo Urbano en la Ciudad de México, on Mexico City scavengers; William Keyes’ Manila Scavengers: Struggle for Urban Survival; and Daniel Sicular’s Scavengers, Recyclers and Solutions for Solid Waste Management in Indonesia. Keyes examined the plight of scavengers and the misguided Philippine government policies towards them in the early 1970s, a study with many implications for Latin America. Castillo exposed the corruption in scavenging in Mexico City and the political clientelism involving the local government, the ruling party (PRI) and scavengers. He was beaten up and received death threats for doing that.

Conducting research on scavenging can be hazardous in other ways too: you must spend a lot of time in garbage dumps, where you are exposed to various toxic substances. The landscape at some dumps I have visited is Dantesque, strewn with dead animals, exuding unbearable stench and buzzing with millions of flies.

The three studies referred to did excellent qualitative analyses of scavenging, but did not get reliable quantitative data, such as number of scavengers, their demographic characteristics, incomes or economic impact. Therefore, I decided that in my research I would use random sampling and quantitative methods in order to obtain reliable numbers on the scavenging population and their activities. I concluded that scavenging was understudied but faced skepticism. When I proposed this as a dissertation topic to my advisor at Yale, he was very supportive. But when I approached another renowned Yale professor, whose name I do not care to remember, he was utterly dismissive. After reading my proposal, he would not even talk to me. He wrote a letter to the dean, telling him that what I wanted to do was garbage. He replied that I would only embarrass Yale if I pursued this topic. Nevertheless, I believe I have proved him wrong. I have received several awards for my research. After my book The World’s Scavengers: Salvaging for Sustainable Consumption and Production came out, both the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank invited me to give lectures, and soon after, both banks started to actively support scavengers. My work has been used to design programs and legislation supporting scavengers in Brazil, Colombia, Argentina and the Philippines. My dissertation, and later my book, were the first to propose a methodology for obtaining reliable quantitative data on scavengers, examine in detail the history of scavenging, as well as demonstrate its linkages with the formal and international economies.

But I faced significant practical obstacles in the beginning. I had to develop a new research design using a joint qualitative/quantitative methodology. I also had to build trust among scavengers for six months before conducting a survey.

Getting middlemen’s cooperation was even harder. Middlemen are the link between scavengers—whose activities are mostly informal and often illegal—and industry. They regularly earn big profits, often exploiting the scavengers. Therefore they try to avoid attention and divulging any “trade secrets.” One middleman in Texas did not even let me finish my request trying to get his cooperation. He told me I was trespassing and threatened to call the police to get me arrested. Luckily, I met a middleman’s son, who provided invaluable insights into the middlemen’s role in the recycling business. I am very grateful to this informant who will remain anonymous.

I encountered a different problem when members of a scavenger co-op asked me to help them get rid of their corrupt leader. It was very hard not to get involved. Even terminology was a problem. Scavenging exists throughout Latin America, but nearly every country uses a different word because the Spanish language lacks a standard term for it. I knew that Mexicans call them pepenadores (derived from Náhuatl, the language spoken by the Aztecs), but not the terms used in other countries. I eventually learned that they are called catadores in Brazil; guajeros in Guatemala; minadores in Ecuador; clasificadoresin Uruguay, recicladores in Colombia; cartoneros in Argentina, and so forth. Buzos, one of the most common terms, is used in Cuba, Costa Rica and Bolivia.

In time I realized that the study of scavenging was not only a theoretical exercise, but that it also had policy implications for development and climate change. My main findings question the following eight myths.

MYTHS ON SCAVENGING

Myth # 1: Scavenging is a recent activity

The belief that scavenging goes back only a few decades is widespread. In fact, scavenging has existed for thousands of years. Humans began to use and refine gold, copper and bronze some 5,000 years ago. They quickly realized that some things left over from the process—as well as old and broken objects—could be melted down and recycled to make new objects. People who recover metals, glass, rags, wood and paper have been around for centuries.

Myth # 2: Scavengers are the poorest of the poor

It is true that scavengers sometimes have very low incomes, below poverty levels in many countries. However, this poverty tends to be caused by exploitation by middlemen and corrupt leaders. If scavengers are not exploited, their earnings can be above the poverty line, in some cases significantly higher. Microenterprises, cooperatives and public-private partnerships have been successful in reducing poverty among scavengers.

Myth # 3: Scavenging is a marginal activity

Scavenging is often believed to be an activity relegated to society’s fringes. This is not true. Scavengers play a fundamental role in supplying raw materials to industry. In Latin America, scavengers have been essential to the paper industry for more than four centuries. Mexico’s paper industry is trying to use as much waste paper and cardboard recovered by pepenadores as possible in order to survive the international competition created by NAFTA. And Brazilian catadores recover about 90 percent of the post-consumer materials recycled by industry in that country.

Myth # 4: Scavenging is a disorganized activity

It is true that many scavengers are unorganized as a labor force. However, they often specialize and have division of labor. In the streets, they sometimes establish territorial divisions. Scavengers also make agreements with local residents, stores and businesses to get exclusive access to waste materials. Garbage dumps and landfills can be highly structured. Hundreds or even thousands of people may work there, and they tend to be organized in order to avoid conflicts. Some dumps resemble factories: they have work shifts, supervisors, and each worker has a specialty. Latin America is the most advanced region in the world in organized scavenging: more than 1,000 scavenger cooperatives and associations exist in the region today.

Myth # 5: Scavenging has a minimal economic impact

This opinion is widely held, but incorrect. In Brazil alone, scavenging has an annual economic impact of about US$3 billion. The World Bank estimates that about 15 million people worldwide work as scavengers. Assuming a median income of US$5 a person per day, their global economic impact is at least US$21.6 billion dollars a year, and about US$7 billion in Latin America. Scavenging cuts down on imports of raw materials, which enables the country to save hard currency. Scavenger-recovered materials are often exported, thus generating hard currency. In Argentina and other countries, for instance, PET, the clear plastic used to make beverage containers is exported to China, where it is recycled into new products.

Myth # 6: Scavenging is a static activity

Scavenging is actually highly dynamic. I was surprised to learn the degree to which scavenging is connected to and depends directly on developments at the national and international level. Population growth and urbanization increase the production of consumer products and the resulting waste materials. The industries that make these products require raw materials. Increased economic activity and international trade also boost the demand for the materials recovered by scavengers. The prices scavengers get paid depend on global supply and demand factors. In times of economic crisis, scavenging tends to rise as a result of unemployment and poverty. Argentina’s 2002 peso devaluation and economic crisis, for instance, dramatically increased the number of cartoneros working on the streets of Buenos Aires and other cities. During the 2008 recession the prices of recyclables dropped 50 percent in just a few months due to lower global demand. Global recycling supply chains now exist, forming a giant loop: Chinese factories manufacture and export products worldwide. And scavengers in the developing world recover recyclables, which then are shipped back to China to start a new cycle. Thus, scavenging is inextricably linked to the global economy.

Myth # 7: Scavengers are a nuisance that must be eliminated

Authorities in most countries consider that scavengers cause problems to society and to themselves and ought to be eliminated. Scavengers may open bags of garbage and scatter their contents onto the streets. Working in dumps poses serious health risks to scavengers. Child labor in trash picking should be phased out. Most municipalities have banned scavenging, but bans only cut scavengers’ income and worsen their living conditions. If governments want to reduce poverty, they should work with scavengers, not persecute them.

Myth # 8: Scavenging has no place in modern waste management systems

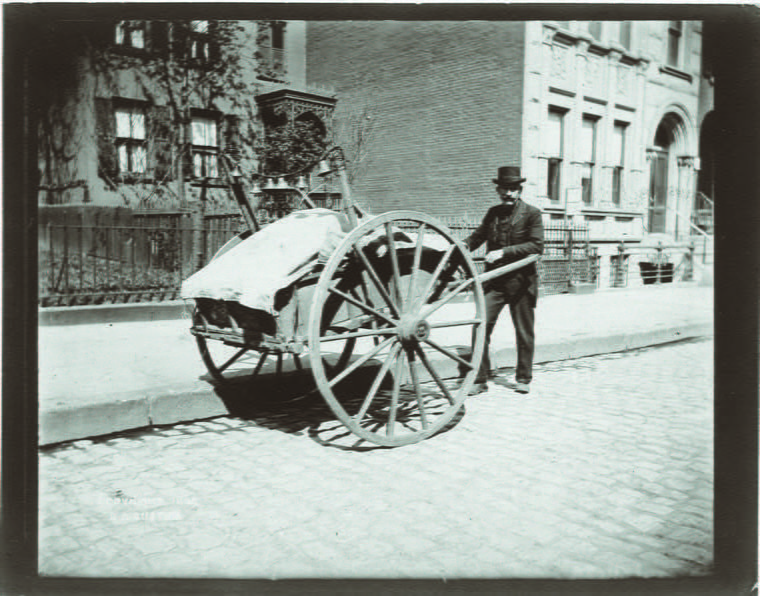

Many government officials believe that the only way to improve waste management is to adopt the same advanced technologies used in developed countries. It is true that scavengers do not play a significant role in formal waste management in the developed world today. In the past, however, when most of their populations were poor, scavengers played an important role in the economy and society in Europe and the United States, particularly in the 19th century. A British researcher living at the end of the 19th century estimated that London had 100,000 scavengers at that time. That number is higher than we can find in most of the megacities in the developing world today. Also at the end of that century, New York City even built a facility where scavengers could sort materials from the city’s trash. Clearly, the city considered scavenging as beneficial and supported it. The socioeconomic conditions in the developed and developing worlds today are completely different, and require dissimilar solutions. Developing countries need to create millions of jobs each year, especially for youths; advanced technologies reduce the number of jobs. Scavengers save cities money by reducing the amount of waste that needs to be collected, and lengthening the life of dumps and landfills. They supply inexpensive recyclables to industry, improving their competitiveness. Recycling saves energy and water; and the industrial processes are less polluting than using virgin resources. Energy savings translate into lower generation of greenhouse gases. Scavengers can be successfully incorporated into the collection, processing, and recycling of source-separated materials, thus reducing their health risks while improving their productivity and their incomes.

SCAVENGING FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT?

Evidence is mounting that scavenging—if government-supported and conducted in an organized and sanitary manner—can be a perfect example of sustainable development: it can create jobs, reduce poverty, prevent pollution, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, conserve natural resources and protect the environment. Therefore scavenging benefits society and public policy should actively support it.

Winter 2015, Volume XIV, Number 2

Martin Medina has collaborated with governments, NGOs, academic institutions and international organizations in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Middle East. He has published widely on the informal recycling sector, community-based waste management, and sustainable materials management. He is currently Sr. International Relations Specialist at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Related Articles

Zero Waste in Punta Cana

I never imagined that my job at a leading Dominican resort would be so dirty—at least not at the beginning. I spent my first months as environmental director of…

A Long Way from the Dump

I am the oldest of five children, and from the time I was little I learned to look for toys and food in Guatemala City’s sprawling garbage dump. My grandmother raised pigs, and I had to be in…

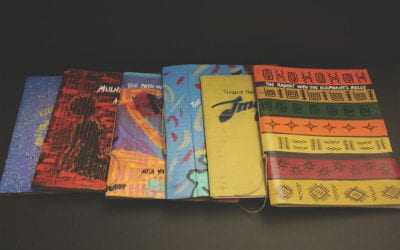

Recycle the Classics

Literature is recycled material, a pretext for making more art. I learned this distillation of lots of literary criticism in workshops with children. I also learned…