Making A Difference: Insects and Internet

Saving a National Treasure in Hispaniola

priceless insect collections have now been digitalized. Photo by Brian Farrell.

On July 11, 2007, the oldest university in the Americas, the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo (UASD), marked the first anniversary of the entry of its natural history collections into the digital global community. These priceless collections record the changing abundances of species over the 20th century, including many species new to science and some that are perhaps already extinct. The collections of insects alone are estimated at more than 50,000 specimens. Add to this innumerable other invertebrates such as spiders, scorpions, plus lizards, plants and fossil specimens, and you have the extraordinary legacy of an unusual man, Eugenio de Jesús Marcano Fondeur, who passed away in September 2003 at the age of 80.

Known as the godfather of Dominican natural history studies, Marcano corresponded regularly with curators at Harvard and the Smithsonian Institution and elsewhere. Known to all as a nearly omniscient biology professor, he is fondly remembered at the UASD as the overseer of “La Cueva,” (the cave) a large basement level space housing his collections and desk, opening via a large garage door to the tree-lined avenue on the spacious campus. Students and visitors were always welcome to visit, but Marcano was very careful—some would say overly so—of his collections. In later years he protected them jealously, but without fumigant or other deterrent to pests that are a constant threat to collections of organic objects.

I had known Marcano since 1989, last visiting him five months before his passing. In La Cueva we spoke of his links to Harvard and of our growing effort to digitize the natural history collections for Hispaniola and the Caribbean, and he expressed great enthusiasm for including the UASD collections. He showed me the insect collections and the great tomes in which he had recorded the data on each specimen, where, when and by whom it was collected, information that normally would be written or printed on tiny labels which, together with the specimen, would be impaled on pin in a specimen drawer. The problem is that if something happens to the books, the collection will lose its scientific value. This time-saving device no doubt helped Marcano keep up the processing of specimens as he collected in near-weekly trips to the field.

After Marcano’s passing, I began conversations with UASD biology professors Manuel Váldez and Ruth Bastardo about stepping in to save the Marcano collections from inevitable deterioration. After two years of negotiation with the university, we were more successful than we hoped. The collections were in surprisingly good shape, and were moved to a spacious, newly refurbished, brightly lit space. Bastardo was appointed curator, in addition to professor. UASD Rector Roberto Reyna and I signed a formal agreement in July 2006. We at Harvard would provide training, equipment and very modest stipends to create a bioinformatics center for UASD undergraduates. The first objective of the center is to bring the Marcano collection to the highest curatorial standards by transcribing and printing modern labels and creating an online database of images and collection information for every species.

We have achieved this and more. With direct oversight by Bastardo and Valdez, the Instituto de Investigaciones de Botánica y Zoología (IIBZ) has become a lively center of research and learning, creating a culture of inter-generational teaching. Now our first generation of Dominican undergraduates, Arlen Marmolejo and Josué Domínguez, trained by MCZ staff at the National Botanical Gardens, are employed by the UASD and engaged in training the second generation of IIBZ biology undergraduates. The experience is as valuable as the product. Students learn the latest techniques of data capture and digital imaging, and feel the excitement of seeing the specimen images online, together with those from Harvard and other world collections. Scientists worldwide are studying the online collections, with the formality of loans of specimens for research now facilitated by their accessibility.

This enterprise started four years earlier with a sabbatical year in Santo Domingo, when I met with Milciades Mejía, director of the National Botanical Gardens (and a UASD graduate and student of Marcano) to inquire of space for an imaging station for digitizing plant and insect specimens. Mejía graciously offered space in the new herbarium building and here we started to digitize specimens collected by our students on the Botanical Garden grounds and elsewhere in the coastal and mountain forests of the island.

These efforts to capture the past, taken together, become larger than their sum by providing a basis for exploration and discovery by future generations. By honoring the achievements of pioneers in science and culture such as Marcano, we forge partnerships based on common appreciation, the basis for any long relationship, and the foundation for making a difference.

Brian Farrell is curator in Entomology of Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, as well as Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology. He spends the summers exploring the Dominican Republic with his wife Irina Ferreras de la Maza, and their children Diego and Gabriela, amidst a very large clan of family and friends.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Dance!

We were little black cats with white whiskers and long tails. One musical number from my one and only dance performance—in the fifth grade—has always stuck in my head. It was called “Hernando’s Hideaway,” a rhythm I was told was a tango from a faraway place called Argentina.

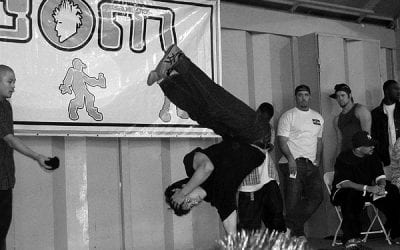

Brazilian Breakdancing

When you think about breakdancing, images of kids popping, locking, and wind-milling, hand- standing, shoulder-rolling, and hand-jumping, might come to mind. And those kids might be city kids dancing in vacant lots and playgrounds. Now, New England kids of all classes and cultures are getting a chance to practice break-dancing in their school gyms and then go learn about it in a teaching unit designed by Veronica …

Dance Revolution: Creating Global Citizens in the Favelas of Rio

Yolanda Demétrio stares out the window of our public bus in Rio de Janeiro, on our way to visit her dance colleagues at Rio’s avant-garde cultural center, Fundição Progresso. Yolanda is a 37-year-old dance teacher, homeowner, social entrepreneur and former favela (Brazilian urban shantytown) resident. She is the founder and director of Espaço Aberto (Open Space), an organization through which Yolanda has nearly …