Más Allá de los Clichés

Dance and Identity in Cuba

Lorna Feijóo and Nelson Madrigal, formerly of the Ballet Nacional de Cuba, pose in front of Havana’s Capitolio. Photo by David Garten

In 1955, the prolific Cuban scholar and ethnologist, Fernando Ortiz, claimed “dance is the principal and most enthusiastic diversion of the Cuban people, it is their most genuinely indigenous production and universal exportation.” Dance may not be the Cuban diversion, but the identification of Cuba with dance certainly surfaces in the popular imagination—most recently in Hollywood’s Dirty Dancing: Havana Nights, and decades earlier as the source of the international mambo craze. But besides its vibrant popular dance culture, Cuba has also produced a sophisticated professional dance scene. In the early 1960s, Cuba’s revolutionary government formed three major national dance companies as well as a rigorous dance training program aimed at developing the art, educating the audience and making professional dance a vehicle for the expression of national identity.

The vitality of professional dance in Cuba today is apparent from the Ballet Nacional to the Tropicana nightclub, the hundreds of folkloric ensembles to the experimental modern dance groups. Every week in Havana promises a polished performance by one of the major national companies formed under the auspices of Castro’s revolutionary government (Conjunto Folklórico Nacional de Cuba, Danza Contemporánea and Ballet Nacional). The city also boasts international biennials in ballet, dance-theater, folkloric dance and, in the near future, modern dance.

Although professional dance in Cuba has, for the past half century, enjoyed significant support, it has not been spared the challenges of the country’s most recent economic and social crisis. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the end of its trade subsidy program with Cuba, the country plunged into a crisis called the “special period.” For ordinary Cubans, the special period has meant severe shortages of basic necessities, the flourishing of a black market and the need to have some access—often illicit—to foreign hard currency. In the vacuum left by the Soviet Union’s trade subsidies, Cuba has propped its economy on tourism, bringing an influx of foreign visitors to the island.

The special period and its multiple effects suffuse dance as well. The material shortages of the special period are certainly visible in the physical deterioration of rehearsal and performance spaces and emigration of skilled dancers, but its social, political and psychic consequences also emerge in the performances themselves. Professional Cuban dance across genres has responded to the new pressures of the special period in both deliberate and unintended ways. Some choreographers and institutions create work to respond to the desires and demands of international tourism, others address the national experience of becoming an object of international desire, and sometimes it is not the choreography that changes but a shift in the performance’s audience and context that radically alter its significance. Performances by these national professional ensembles embody distinct versions of Cuban identity that may portray an official agenda and simultaneously betray unofficial elements of Cuban experience.

It was the mythic association of Cuba with dance that initially compelled me to travel there. I arrived in spring 2003, imagining a place where dance practically erupted in the streets. Within my first few weeks in Cuba, I became deeply absorbed in el folklor—the Cuban term that usually refers to the dance and music associated with Afro-Cuban tradition. Cuba supports hundreds of dance companies dedicated to a folklor repertory ranging from internationally acclaimed professional companies to amateur groups. The Havana-based Conjunto Folklórico Nacional (CFN) has defined the genre since 1962 when it was formed by the revolutionary government with a mission to collect, document and preserve Cuba’s original dance and music heritage. The CFN’s process of collection and codification recast the dances of Cuba’s historically marginalized black population as an embodiment of national identity.

Every Saturday, starting in 1979, the CFN performs at El Palenque—the sun-lit, open-air patio adjacent to the company’s studios. On recent trips to Havana, I had joined the mix of foreigners and Cubans drinking beer and hunting for a patch of shade in anticipation of the afternoon show. There is no raised proscenium stage, no lights or curtain and the audience surrounds the performers on three sides. The intimacy and informality of the space and its name, which refers to a runaway slave settlement, suggest the mythical origins of the CFN’s repertory among the black slave population of Cuba’s colonial past.

In contrast to the contrived informality of the performance space, the show is meticulously choreographed and rehearsed. An authoritative emcee presides, whose gravely serious introduction to each dance is a reminder of the CFN’s mission to educate Cubans about their heritage. The musicians gathered in one corner of the performance space still include an older generation of CFN members whose knowledge of folklor was learned from family and friends. In contrast, the company’s young dancers brandish skills acquired at the competitive arts school, El Instituto Superior de Arte.

The dance repertory of the first half of the performance is typically a dramatized version of Afro-Cuban religious ritual. The second half promises rumba, the secular Afro-Cuban partner dance selected by the Castro government from a range of popular dances as the official national dance. In her book Rumba: Dance and Social Change in Contemporary Cuba, Yvonne Daniel explains that historically, rumba was the dance of “the slave, free black, mulatto and white workers of the nineteenth century” and its selection was meant to express the revolution’s ideology—if not actual practice—of “equality with the working masses and an identity with [Cuba’s] Afro-Latin heritage.”

During the rumba portion, the stage/audience boundary dissolves as people leave their chairs to dance and sing along to rumba, often pulling an unsuspecting tourist out of the crowd to participate. While in the 1980s, only Cubans and a few foreign diplomats attended these performances, the audience is now made up of tourists and Cuban hustlers or jineteros [or jineteras?] aggressively offering sex or cigars to foreigners. The CFN’s display of Afro-Cuban culture that began as an iteration of certain revolutionary values takes on another meaning in the tourism economy where visitors from North America and Europe are enticed by the promise of exotic entertainment.

The exploitation of el folklor and the attendant sexualization of dark-skinned Cubans hinted at in the El Palenque performance are explicit in the cabaret shows performed at major hotels and resort complexes. These floor shows, virtually unchanged since Cuba’s tourism heyday in the 1940s and 50s, feature scantily clad and outrageously plumed and sparkling mulatas alongside exaggerated and stereotyped versions of folklor. While the CFN performance continues to serve both local and tourist audiences, the cabaret shows are prohibitively expensive for Cubans and aimed squarely at outsiders. The appropriation of Afro-Cuban identity that once fulfilled a need for a distinct national cultural identity becomes, in the tourism market, a fulfillment of desire.

Even as the ideology and history of the CFN distance it from the cabaret, early CFN collaborator Argeliers León laments to CFN historian Katherine Hagedorn in her book Divine Utterances: The Performance of Afro-Cuban Santería that some of the spectacle and sizzle of the cabaret has infiltrated the CFN’s supposedly “authentic” presentations. Not only folklore, but all of Cuba’s dance genres, are increasingly haunted by the cabaret and the expectations it places on Cuban dance performance from the outside.

During my most recent trip to Havana, I met with Noel Bonilla, director of modern dance for Cuba’s National Council of Performing Arts. Bonilla expressed enthusiasm for my interest in exploring Cuban dance “beyond the clichés.” When I asked him what he meant by “the clichés” he reeled off the now-familiar cabaret stereotype: “the mulata, the palm trees, the sun,” but also expressed frustration with the “worship of the diva—Alicia Alonso.” Indeed, outside of Cuba, Cuban dance is synonymous with Alonso, the founder and current director of the Ballet Nacional de Cuba. A decade of Dance Magazine articles on Cuban dance focuses exclusively on the performances in Cuba and abroad of the Ballet Nacional.

During the early years of the revolution, when the CFN was formed from scratch, Alicia Alonso’s international reputation was well established. But it was direct support from the government that allowed her small private company to become the Ballet Nacional de Cuba. While the Conjunto appealed to the revolution’s ideological association with working-class Cubans, the comparatively elite, bourgeois and Eurocentric associations of classical ballet were discordant with early revolutionary ideology. Yet Castro’s government gave significant support to both.

When it is not touring, the Ballet Nacional performs in the spectacular but dilapidated colonial Gran Teatro in Old Havana—a renovated part of the colonial city that has become a major tourist attraction. Inside the theatre, a semicircle of balconies rises to a painted fresco and chandelier above the proscenium stage. The well-worn red velvet seats and curtains create a setting quite different from that of El Palenque. In a sense, the two performance spaces reenact the old colonial relationship of European and African culture. The persistence of these historic associations is apparent in the dancers as well. In the Ballet Nacional, dark-skinned dancers are the exception and vice versa in the CFN.

Ballet not only has elite connotations, but it is also less distinctively Cuban than folklore. Alonso and the Ballet Nacional are a point of national pride, but less for any particular style than for their tremendous technical abilities and fiery performance presence. Ballet itself is a multinational art, one that cannot be claimed by any single nation. In that sense, ballet has an international dance identity and through the excellence of the Ballet Nacional de Cuba, the tropical third-world island symbolically demonstrates its ability to rival European and North American superpowers, especially during the special period.

The third major professional dance institution to emerge in the early years of the revolution, along with the CFN and Ballet Nacional, is Danza Contemporánea de Cuba, the modern dance company. Unlike ballet, its development was entwined with folklor. Ramiro Guerra, widely considered the grandfather of modern dance in Cuba, was early director for both the CFN and Danza Contemporánea de Cuba. In a recent interview, former Danza Contemporánea soloist, Marianela Boán, described the ideological attraction of modern dance in the early days of the revolution: “modern dance, having no pre-established vocabulary, allows searching of the source of expression in the cultural roots of each country. Modern dance allowed us to develop our own way of movement…far from the Eurocentric ballet and open to the inclusion of our folkloric roots.” Yet today, Noel Bonilla feels that while Cuba has developed formidable dancers, it is still struggling to find an original and authentically Cuban voice independent of both North American and European material and haphazard appropriation of folklor.

Danza Contemporánea, in a manner similar to the Ballet Nacional, is less remarkable for its Cuban-created repertory than for the international caliber of its dancers. Fresh and experimental choreography is found among the cluster of smaller companies including Retazos, Compañía Narciso Medina and DanzAbierta, which split off from the company in the 1980s during an especially “open” moment in the Castro government’s attitude toward artistic expression. During the early years of the special period, these dance outfits explicitly addressed the conditions of contemporary Cuban existence in the content of their work. A piece by Marianela Boán for DanzAbierta entitled El Pez de la Torre Nada en el Asfalto, premiered in 1996, was not only experimental in its use of the genre but bold in its confrontation of Cuban experience. I did not see the piece, but in an interview, Boán described some of it for me. As the audience enters the lobby of the performance, the dancers approach them attempting to trade absurd things as though part of the underground black market that has flourished during the special period. On stage, the company dances with suitcases in a nod to the unspoken national obsession with emigration. The rags that the dancers wear are gradually discarded and they discover below them a second skin of sparkling cabaret costumes. While they dance a show in the cabaret style, they hold empty plates and forks in reference to the dull hunger behind all the glamour.

Boán’s piece addresses not only the strains of the special period through dance, but addresses the very issue of Cuban dance identity. She uses Cuban dance stereotypes like pieces of a collage, altering their connotations as she places them in a new context. The meaning of the piece depends on knowledge of the history and context of those fragments even as Boán rejects them as incomplete and inauthentic.

Boán’s piece points to the possibility that there is something distinctively Cuban in even the most commercial and exploitative genre. The identification of Cuba with dance articulated in Ortiz’s generalization feeds on clichéd forms. But it also acknowledges the potential for dance to address and reflect contemporary Cuban identity and experience. This association of Cuba and dance constrains as well as inspires Cuban choreographers and dancers developing a voice in the medium. Their work promises to be an ongoing process of discovering and describing contemporary Cubanidad.

Anna Walters graduated from Harvard in 2006 with a B.A. in Folklore and Mythology. Her thesis, “Danced Belief: Embodying Orishas in Matanzas, Cuba” addresses the dynamics of dance as folkloric spectacle and sacred practice. Anna lives in Denver, Colorado.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Dance!

We were little black cats with white whiskers and long tails. One musical number from my one and only dance performance—in the fifth grade—has always stuck in my head. It was called “Hernando’s Hideaway,” a rhythm I was told was a tango from a faraway place called Argentina.

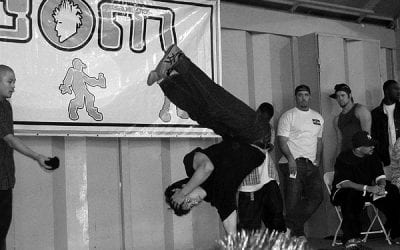

Brazilian Breakdancing

When you think about breakdancing, images of kids popping, locking, and wind-milling, hand- standing, shoulder-rolling, and hand-jumping, might come to mind. And those kids might be city kids dancing in vacant lots and playgrounds. Now, New England kids of all classes and cultures are getting a chance to practice break-dancing in their school gyms and then go learn about it in a teaching unit designed by Veronica …

Dance Revolution: Creating Global Citizens in the Favelas of Rio

Yolanda Demétrio stares out the window of our public bus in Rio de Janeiro, on our way to visit her dance colleagues at Rio’s avant-garde cultural center, Fundição Progresso. Yolanda is a 37-year-old dance teacher, homeowner, social entrepreneur and former favela (Brazilian urban shantytown) resident. She is the founder and director of Espaço Aberto (Open Space), an organization through which Yolanda has nearly …