Mexican Yiddish and Secular Jewish Identity in Mexico

Writing to Exist

Visitors to the Casa Azul in Coyoacán, Mexico City, can walk through the house of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, admiring their collections of folk art, oddities, masterpieces, and furniture. As a student of literature, I was most drawn to their bookshelves during a visit there several years ago. Among the numerous volumes, I noticed three copies of an unusual Yiddish book that Rivera himself had illustrated: Shtot fun palatsn, City of Palaces. This book of poetry, published in 1936, includes meditations on poverty, lush descriptions of the Mexican landscape and an uneasy negotiation of national identity. Written by the Yiddish poet Isaac Berliner, it represents a Jewish immigrant’s encounter with his new, Catholic country.

Berliner’s City of Palaces features 73 poems in Yiddish about so-called secular, non-Jewish subject matter. As mentioned, the book most notably features illustrations by Mexican muralist Diego Rivera who, in the lore that accompanies this artifact, entertained a friendship with Berliner and other Yiddish intellectuals in Mexico City who shared his leftist political leanings. Many are familiar with the specious links to Jewish heritage claimed by Diego Rivera; on different occasions the artist claimed he had converso heritage—meaning his ancestors had converted to Catholicism during or before the Spanish Inquisition—or self-identified as a Jewish person (similarly, Frida Kahlo also maintained that she had Jewish heritage on her father’s side, a claim that has since been disproven). Rather, Rivera’s claims to Jewishness seem to have been connected to his political outlook. It served as a way for him to assert solidarity with Jews, especially during the 1930s and ‘40s, when virulent anti-Semitism was not only sweeping Europe, but also a problem in Mexico. Over the years, the question of Diego Rivera’s Jewishness has received attention from scholars and journalists alike, though little has been said about his artistic collaboration with the Yiddish poet Isaac Berliner, whose work has largely been forgotten.

The Jewish minority in Mexico in the 1920s and 30s was made up of several different ethnic communities distinguished mainly by their national origin. These groups included Sephardic Jews from Aleppo, Damascus, and the Balkans, and Ashkenazi Jews who were mainly from Poland and Lithuania. Though they were all Jewish, these groups had distinct religious and linguistic preferences, their own synagogues, and particular areas of the city where they settled. Isaac Berliner, an Ashkenazi Jew, was one of the many Jewish immigrants who had recently arrived from Poland. Like other newcomers from Eastern Europe, he had been raised in what Mexican-Jewish writer Ilan Stavans has described as “a secular, left-leaning environment that was suspicious of religion.” Such an attitude toward Jewish religion had been the subject of much discussion over the previous decades, first in Europe, but then in the Americas and elsewhere Jewish communities were formed.

These new Jewish movements had a particular interest in rethinking the place of religion in Jewish life, and they included a range of ideologies, including Zionism, which argued for the establishment of a national Jewish homeland in Palestine, but also secular Yiddishism. Yiddish, the language historically spoken by Jews in Eastern Europe, is a Germanic language with components from Hebrew, Aramaic Latin, and Slavic languages. Until the Holocaust, there were millions of Yiddish speakers. Today, the majority of those who continue to use Yiddish as an everyday language are ultra-Orthodox, rather than secular. Today, although there are a growing number of secular Yiddish speakers, the vast majority of those who continue to use Yiddish as an everyday language are ultra-Orthodox.

In Berliner’s time, Yiddishism represented a possibility to create a kind of secular Jewish culture that built on aspects of Jewish customs and heritage, but that was divorced from traditional ideas of Jewish practice. In other words, for Berliner and other Yiddishists like him, this language and its literature presented a new kind of non-religious identity that was still authentically Jewish. Yiddish literature and culture were also transnational. They connected Berliner to other Yiddish-speaking Jewish communities spread out around the world, and it also allowed immigrant writers to propose hybrid identities between their Jewish (Yiddish) selves and the local, national contexts where they lived. Like Jewish immigrant writers in the United States at the same time, Berliner used Yiddish poetry to explore what it meant to be Jewish in a new national environment. Writing about Mexico in Yiddish was a way for Berliner to propose a new kind of Jewish identity, one that was both authentically Jewish and Mexican.

The 1930s and ‘40s was a time of great confluences for the young Ashkenazi community in Mexico. There was a pressing need for the community—founded in the mid-20s—to decide on its ideological stance vis-à-vis religion. The violent political insecurity in Europe cut ties between immigrants and their home countries, extending, too, to the literary networks that connected Yiddish writers who were read between Europe and the Americas. But perhaps most pressingly, the local, public discourse in Mexico about the character of the nation had strongly racial tones that excluded Jews.

At the end of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1924) there was a movement to re-think “modern Mexico” as a nation. Different ideas about what it meant to be Mexican were being publicly debated among politicians, intellectuals and artists. In 1925, for example, José Vasconcelos, the secretary of education at the time, published his famous essay La raza cósmica, in which he argued that a “fifth race” would emerge from the Americas, a mixture of all of the existing races on earth, and one with their best qualities. With a similarly positive attitude toward racial mixing, the idea of mestizaje became a popular way to think about Mexican identity. Claiming the cultural inheritance of both Spain and Mexico, for many mestizaje represented the ideal modern Mexican. As anthropologist Ana María Alonso points out, this promotion of racial and cultural mixing was an attempt to recast Mexico’s fragmented national identity into one that was strong by turning heterogeneity into homogeneity.

On one hand, it is interesting to note how mestizaje stands in opposition to other contemporary racial theories, like that of Nazi Germany around the same time, or even in the United States where racial mixing was also understood to be a threat to national identity, not the source of it. On the other hand, mestizaje still imposed barriers to belonging, as it reinforced particular kinds of racial hierarchies that privileged “mixture” over the indigenous and excluded non-Latin American immigrants. This made it difficult for immigrants from Eastern Europe to find acceptance as Mexicans.

In addition to the exclusion of the outsider, this method of thinking also led to stigmatization of the insider—Mexico’s large indigenous population. The aesthetics of mestizaje, which were on display in the public art of modernists like Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, proudly celebrated indigenous imagery as a part of Mexican identity. On one hand, the figure of the indigenous person was an important pillar of the kind of racial identity that Mexican modernism proposed and connected modern-day Mexicans to an ancient heritage on Mexican land. However, in a subgenre of Mexican modernism known as indigenismo, this artistic focus on the indigenous figure could also be exoticizing, and it also depicted indigenous people as inferior or even primitive in comparison to the new, modern Mexico of the 1930s and ‘40s. Therefore, what seemed to be a positive aspect of racial inclusivity actually reflected a kind of hierarchy that maintained the dominance of the mestizaje, those with Spanish roots. Mestizaje muralists and writers reinforced this structure by depicting the indigenous this way in their art.

Isaac Berliner entered into this national conversation about what it means to be Mexican, and he did so as an immigrant, as an Ashkenazi Jew whose partnership with Diego Rivera gave him a mark of legitimacy. Though Berliner’s use of indigenous sites and peoples now reads as insensitive, we can also see how he was trying to write Jews into the foundational narratives of the Mexican nation by adopting aspects of indigenismo in his own poetry. In in his poem “Teotihuacan,” for example, Berliner writes about the ancient Mesoamerican city known for its famous pyramids.

And maybe my great-great-grandfather stepped on you here

And left a faraway secret to inherit in my blood, — —

And maybe my genesis is covered under your stones

in eternal silence over unending times? — — —

…

Maybe your builders came from Egypt,

From Phonecia,

Or were they Jews? — — —

(un efsher hot mayn elter-elter-zayde do af aykh getrotn

un hot gelozn beyerushe in mayn blut a sod a vaytn, — —

un efsher ligt mayn urshrpung unter shteyner ayere fartrotn

in shvaygn aybikn durkh loyfn fun unendlekhe tsaytn? — — —

…

Efsher shtamen dayne boyer fun egiptn,

Fun fenitsie,

Tsi fun yidn? — — — )

Berliner attempts to weave two ancient stories together, contrasting the pyramid-builders of his own ancestry with those of his new country. Berliner also draws on a shared experience of suffering; both the Jews and the indigena were historical victims of the Spanish Empire. With a shared oppressor, Berliner synthesizes the violence of the Inquisition and the Conquest, dramatizing the historical intersection of Jewish and indigenous.

I know, here was the Spanish Inquisition

With their holy Christian faith

Staining the name of Toltec

(Ikh veys, es hot do shpanies inkvizitsie

Mit ir kristlekh-heylik gloybn

Ayngeflekt dem nomen fun toltek)

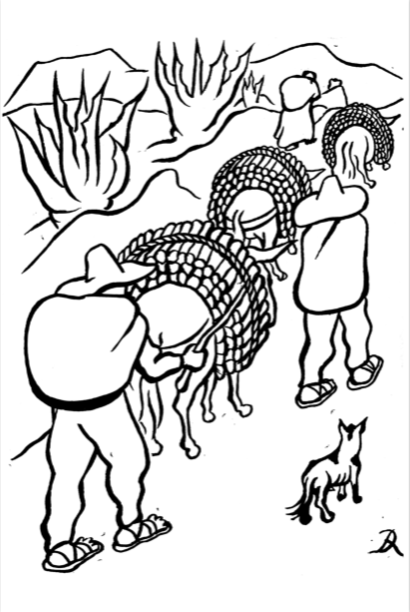

In another poem, his Yiddish is accompanied by Rivera’s illustration on the accompanying page, an image of a quiet desert road “In the Abyss of the Day”

I love to stand like this and wait […]

I love to stand like this and look at mountain roads […]

I love the slow trudging of donkeys […]

I love the scattering of sunny speckles […]

I love the earth-body fried-up from glowing heat […]

I love to stand on the mountain paths and wait.

(hob ikh lib azoy shteyn un tsu vartn […]

Kh’hob lib azoy shteyn un tsu kukn af bargike vegn […]

Kh’hob lib dos pamelekhe sharn fun ayzlen […]

Kh’hob lib dos tsepaln fun zunike flekn […]

Kh’hob lib dem tsepregeltn erd-guf fun gliike hitsn […]

Kh’hob lib af di bargike vegn tsu shteyn un tsu vartn.)

In this poem, Berliner looks to the Mexican landscape, describing slow midday moments in the desert heat. Compared to his industrial hometown of Lodz, the quietness of nature, the sun and the desert would indeed have been a novelty for the immigrant writer. But in celebrating the mundane panorama of a mountain road, the poem is not merely a mediation on local color. The scene becomes an occasion for Berliner to proclaim his love for his new country. Indeed, the refrain “I love” (kh’hob lib) appears six times—once in each stanza, each time focusing on a different aspect of the stillness of the scene.

Though Berliner’s poems do not often address themes of an explicitly Jewish nature, their Jewishness is, nevertheless, marked visually by the Yiddish letters on the page, presented alongside and in dialogue with Rivera’s illustrations. Berliner’s book of poetry not only evinces a connection between the famous artist and members of the Jewish community in Mexico City, but it also shows how Berliner was working through the idea of what it could mean to be both Jewish and Mexican. Adopting popular artistic modes of mestizaje and indigenismo in his work, Berliner’s poetry combines his own Yiddish words with Rivera’s iconic Mexican style.

Winter 2021, Volume XX, Number 2

Rachelle Grossman is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Comparative Literature at Harvard University. She researches Jewish literature in Latin America and Eastern Europe and the connections between these regions.

Related Articles

Poetry and History in 18th-century Brazil

In his presentation of the beautifully published volume, Obras Completas de Alvarenga Peixoto, historian Kenneth Maxwell turns our attention to one of his specialties, the late 18th-century

Religion and Spirituality: Editor’s Letter

Religion is a topic that’s been on my ReVista theme list for a very long time. It’s constantly made its way into other issues from Fiestas to Memory and Democracy to Natural Disasters. Religion permeates Latin America…

Buscando America: A Sephardic Pre-History of Jewish Latin America

When I give public lectures about Conversos and Sephardim in the Americas, whether it is in the United States or South America, I always get at least one question, “Columbus was Jewish,