Mexico’s Energy Reform

National Coffers, Local Consequences

The small, white-washed classroom at the University in Minatitlán, Veracruz, was packed with a couple dozen people who, although neighbors, had never met. Several members of a fishing cooperative, a pediatrician, a toxicologist from Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), a biologist turned environmental activist, a couple of retired oil workers, a Pemex engineer, two medical students, neighbors of the local refinery, and community activists all turned out to discuss relations between Pemex and surrounding communities.

Invited by my colleague, the historian Christopher Sellers from Stony Brook University, to this unusual witness seminar, participants squeezed around tables set up with tiny voice recorders. I had a supporting role, helping to manage the meeting and translate if necessary. I was also thrilled to visit for the first time Minatitlán and its twin down the road, the port of Coatzacoalcos, the hubs of the oil and petrochemical industry in southern Veracruz and two of the most polluted cities in Mexico.

The reason for my excitement had its own history. Two decades earlier, as a fresh-faced graduate student in the history department at the University of California, Berkeley, I had decided to write a dissertation about the history of the oil workers of Minatitlán, the most important refinery in southern Mexico before President Lázaro Cárdenas nationalized the industry in 1938. However, my project was soon derailed. Every jarocho (the endearing term for Veracruz natives) I spoke to told me that staying in Minatitlán or Coatzacoalcos for any extended period of time was a terrible idea, even more so as I had planned to bring my four-year old for the six-month research trip. I was skeptical of this advice until I met the friend of a professor with young children. She was from Minatitlán originally but left it for Xalapa not only seeking better employment opportunities but also running away from the pollution that gave her children asthma and made their skin break out in hives with every bath. I then switched the focus of my investigation to the history of labor, environment and oil in northern Veracruz. I had never visited Minatitlán until now.

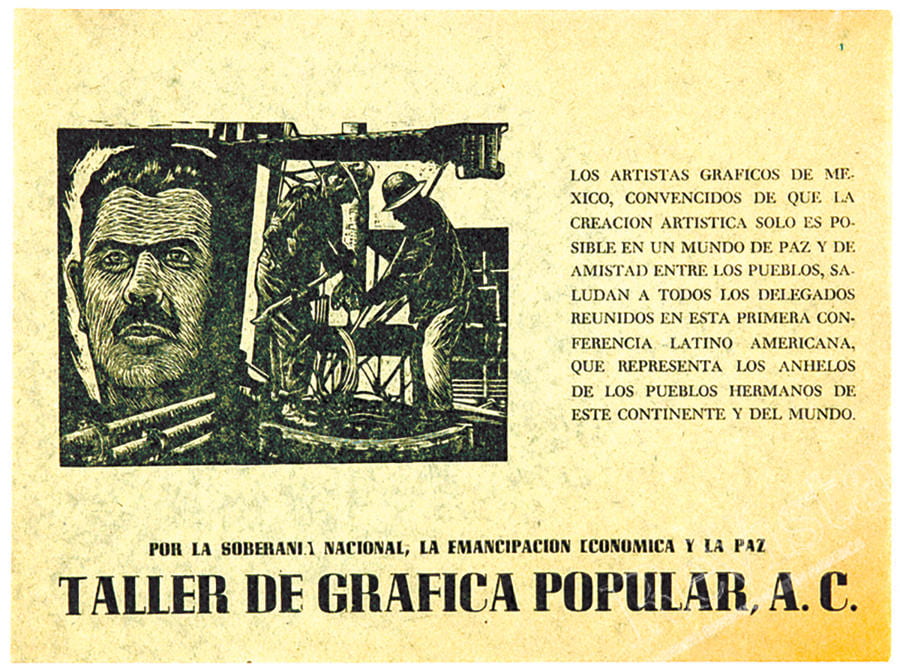

Jesús Álvarez Amaya and his “People’s Graphic Workshop” made prints to support the expropriation of Mexican oil decreed in the 1930s. Courtesy of Taller de Gráfica Popular.

Knowing the history of the place, I expected no surprises from the accounts of the seminar participants. The first round of anecdotes was formal and guarded, as one could anticipate. But as soon as the men and women felt comfortable and before the temperature in the classroom reached sauna stage, the tone changed. The mood became somber. Everyone in the room was sick, had been sick, or knew someone in their families who was sick. Their ailments, as the mother of my son’s playmates had told me two decades before in Xalapa, ranged from recurring skin rashes, to constant allergies, to asthma, to digestive system discomfort, to leukemia. The pediatrician himself had had leukemia and when he realized that too many of his patients also had the disease, he began asking questions. He wanted to know how many leukemia cases existed in Coatzacoalcos-Minatitlán or whether there were other cancers in the region. It turned out that no such records existed: no numbers, no statistics, no cancer registry of any sort. No one kept track and no one encouraged him to do so either.

I have been thinking about those stories in light of the energy reforms enacted by President Enrique Peña Nieto and implemented by the Mexican Congress in August 2014. The reforms amended the Mexican Constitution in two ways. First, they broke the monopoly that Pemex had on hydrocarbons (oil, natural gas, and petrochemicals). Second, they allowed private investment, both foreign and domestic, to return to the industry.

While there is no denying that Pemex generated great wealth for Mexico as a whole, the gains are not unequivocal for Pemex’s workers and neighbors. As Minatitlán-Coazacoalcos demonstrate, ecological degradation followed the oil industry, eroding the local community’s health in the process. As the Pemex toxicologist explained in the seminar, the company, cognizant of the fact that the petroleum industry ranked among the most dangerous in the country, has made quantifiable strides in monitoring the health of its permanent workers and created a robust health system for union members. It never occurred to him personally, however, that neighbors of the refineries and the petrochemical plants deserved similar attention since they were exposed to the same toxins the workers confronted on the job on a daily basis.

Will the oil sector reforms bring change for the better? The shift in ideological and economic policy direction was jarring for Mexicans, controversial and contentious. Weeks of demonstrations, marches and protests framed the congressional debates and with good reason. Mexico had decreed the first major nationalization of petroleum in history, coming after three decades of conflict among the workers, the state and the foreign oil companies, following the first social revolution of the 20th century (1910-1920). The decision to nationalize the oil industry in 1938 catapulted President Cárdenas to the pinnacle of the pantheon of revolutionary heroes among Mexicans. He remains there to date despite more critical reviews by historians and sundry academics. The public’s attachment to the principle of national ownership of the oil industry, therefore, cannot be underestimated, no matter how critical ordinary Mexicans are of Pemex, the oil workers’ union and the government.

Peña Nieto knew that a strong nationalist flame burns within every Mexican, so he promulgated the reforms in such a way that he could truthfully claim that he was not privatizing Pemex and that he was not denationalizing oil. The language of the constitutional amendments was careful and specific yet flexible. Arguing that he acted in Cárdenas’ spirit, Peña Nieto drafted an amendment that reaffirmed the late president’s stipulation that no concessions would be granted to private parties, but he added that the nation could assign contracts to private companies directly or through Pemex. In all cases, the contracts would declare that the hydrocarbons in the subsoil belong to the nation.

Thus Peña Nieto assured the Mexican people that Pemex was not privatized. It continues to exist as a state-owned company, but it will collaborate and compete with private firms, both foreign and domestic. Investors drilling on land and offshore will not own the crude oil or natural gas they find. Those products will be owned by the nation, so Mexico’s oil riches continue to be nationalized. However, private interests will gain access to hydrocarbons through contracts signed with the government or Pemex. The language of each contract therefore will determine if a private company keeps a percentage of production, pays a set price per barrel of crude or cubic meter of natural gas, pays extraction or export taxes, etc. As critical journals like the weekly Proceso and the daily La Jornadahave noted, the contract is the undefined and crucial concept in the reforms—the artifact that will contain the details that could undo Pemex if it can’t compete against transnational oil companies.

One goal of the reforms is to obtain new technologies. Observers believe that the government specifically wants two technologies: “ultra deep” offshore drilling and hydraulic fracturing. Although Pemex has been drilling off the coast of Tabasco and Campeche since the 1970s, the crude that the companies are seeking now lies at 2,900 meters (9,500 feet) below the surface (by comparison, the British Petroleum-Deepwater Horizon well that exploded in 2010 and dumped some nine million barrels of oil in the Gulf of Mexico was at 1,500 meters, or 5,000 feet). Mexico estimates that 50 billion barrels of oil are buried in Gulf waters ready for retrieval with cutting-edge technology.

“Unconventional” oil, specifically shale oil extracted by using the method known as hydraulic fracturing, is another priority for Mexico. The process involves injecting water, sand and chemicals one mile into the earth to crack the shale and release oil and gas. The technology is water-intensive, using two barrels of water per barrel of oil captured. It also creates toxic waste that can contaminate the water table when it is re-injected into the bedrock to protect the environment aboveground. And it provokes earthquakes. For example, on April 4, 2015, the New York Times reported that Oklahoma had surpassed California as the shakiest state, experiencing 5,417 quakes in 2014, a remarkable increase from 29 tremors in 2000. The difference in that decade was 3,200 wastewater wells dug to bury the poisons brewed through “fracking.” Industry analysts estimate a potential 150 million barrels of shale oil in northern Mexico, but Pemex has been able to bring only one well into production. If the company acquires advanced technologies through joint ventures or contracting, what will happen to local communities?

The Gulf of Mexico and the deserts of northern Mexico are sensitive ecosystems. The Gulf is an important fishing ground for both the United States and Mexico. As the 2010 British Petroleum spill demonstrated, accidents in the Gulf are deadly for workers (eleven workers died in the BP blast) and harmful for coastal communities dependent on clean beaches and water for their livelihoods. In Tabasco and Veracruz, fishermen affected by the 1979 Ixtoc 1 underwater fracture that blew out the well saw stocks recover after three years, although the fish they caught were not the same species as those previous to the spill, according to biologists from Mexico’s national university. The effects of the BP spill on the Louisiana fishing fleet are still being fought over in court, five years after the accident.

In northern Mexico, water is already at a premium. Industry analysts, in fact, declared to the online trade journal “DrillingInfo” in December 2014 that the lack of water is an issue for the Sabinas and Burro-Picachos shale fields of Coahuila. That area is rural, forcing ranchers and farmers to compete with oil companies for water. Moreover, as the New York Times reported on April 11, 2015, the Rio Grande is already strained by the drought affecting the U.S. Southwest. By the time the river reaches the Gulf, it is but a trickle. Research about the maquiladoras (textile assembly plants) on the border also show that the Rio Grande is severely polluted by industrial waste, compromising the health of communities on both sides. Adding the burden of fracking to the Rio Grande and local aquifers will mean that those localities will have even less potable water and more toxic waste. Under any standard, such conditions spell hardship for local populations.

An iguana enjoys its natural habitat, part of the sensitive ecosystem threatened by the oil industry. Photo by Myrna Santiago.

Lastly, there is violence to consider. The use of new technologies will open new areas for extraction, expanding the geographical potential for bloodshed. By most accounts, the Mexican drug cartels that traffic along the Tamaulipas-Coahuila-U.S. border have diversified their criminal activities to include fuel theft. As the Financial Times of London pointed out in a November 12, 2014 article, the shale fields “encroach on cartel turf” and could be dangerous for workers. One anonymous executive confessed that in the undisclosed area where his company provided services to Pemex, workers arrived by helicopter, escorted by the Mexican military. But despite the risk to workers’ lives, consultant Emil de Carvalho told the Financial Times that no company would shy away. The firms would simply adjust their budgets to include security personnel. There is simply too much money to be made to be derailed by the prospect of violence against workers. If Nigeria is an example, Mexican and foreign oil workers’ safety will be secondary to extraction.

The reforms might achieve the ultimate goal of filling the coffers of the Mexican treasury with oil profits, but as the Minatitlán witnesses revealed, the local costs might be very high.

Fall 2015, Volume XV, Number 1

Myrna Santiago is professor of history at Saint Mary’s College of California. Her book, The Ecology of Oil: Environment, Labor and the Mexican Revolution, 1900-1938, won two prizes. She is working on a history of the 1972 Managua earthquake and is looking for witnesses willing to tell their stories: msantiag@stmarys-ca.ed.

Related Articles

Wind Energy in Latin America

English + Español

Carlos Rufín is Associate Professor of International Business at the Suffolk University’s Sawyer Business School, and a consultant on energy matters to the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank…

Brazil’s Oil Scandal

When I moved to Brazil in the giddy days of 2011, many people were voicing that phrase. After all, the economy seemed to be sizzling after posting 7.5 percent…

Routledge Handbook of Latin America and the World

On December 17, 2014, after U.S. President Barack Obama and Cuban President Raúl Castro simultaneously announced the decision to move towards…