Midnight in Mexico

Press Challenges: A Personal Account

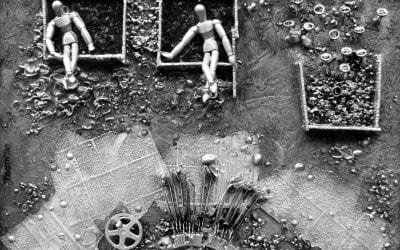

Elias Ramirez, 32, of Morelia, Michoacán, was killed on his motorcycle January 1, 2009. Photo by Daniela Rea.

More than 60 Mexican journalists have been murdered and dozens more have disappeared since 2000, more than 30 in the past four years.

Every journalist in Mexico—sometimes even I, an American journalist—wakes up to ask the following questions: How far should I go today, what questions should I ask, or not ask, where should I report, or what place should I avoid? And what photos should I take, or ignore. Should I wear a wig, pretend to be a taco or an ice cream vendor at the crime scene so that I can disguise myself as I try to do my job, which likely means reporting on the latest decapitated body on the streets, or a hanging from a bridge in downtown Juárez, Cuernavaca, Nuevo Laredo or Monterrey.

Should I even answer my cell phone? Because I know that if I do the person calling me is surely a man who calls himself Boots, Rooster, Chicken or Rabbit, a spokesman for the drug traffickers. And once I answer that phone I have no leverage to negotiate. It’s either follow an order or face death, or the killing of a relative, a son, or daughter because that’s the reality in Mexico for a journalist today. The intense questioning, the doubts and the anxiety and stress have many of my Mexican colleagues and us on edge.

My colleagues and I are witnessing the bloodiest period in Mexico since the 1910 Mexican revolution and the biggest threat to Mexico’s national security, its young, fragile democracy and freedom of the press.

Mexico today is among the most dangerous places to do journalism in the world, right up there with Iraq, Russia and Somalia. This is especially true for those of us who cover the U.S.-Mexico border, once a frontier for Mexicans seeking new opportunities and new beginnings.

In the border city of Ciudad Juárez, across from El Paso, more than 200,000 people have fled the chaos, many to the United States. Today, parts of the border region are increasingly silent. Our beloved border is now paralyzed by fear and chaos and stained by bloodshed. More than 36,400 people have been killed since Dec. 2006, nearly 8000 in Ciudad Juárez alone since January 2008.

Whatever danger we U.S. correspondents face pales in comparison to the dangers faced by our Mexican colleagues. I can call my editor, Tim Connolly, this very second and say, Tim, I don’t feel safe anymore and he’ll say, get on the next flight out. That’s not the case for Mexican journalists.

Let me explain it to you this way: the difference between my Mexican colleagues and me comes down to this: citizenship. I’m thankful and grateful to have parents who many years ago dreamed big and were determined to give my five brothers—Juan, Mario, Francisco, David, Mundo and two sisters—Monica and Linda—and me the chance to dream and achieve. We migrated from a poor community in Mexico to follow the crops in this country when I was just six years old. Along the journey, from Durango to Juárez, California to Texas and back to Mexico, I was able to obtain a little blue passport that says I am a citizen of the United States of America.

As imperfect as our judicial institutions are, I have perhaps a naïve, but unwavering belief that if something is to happen to me, there would be consequences to pay. That our newspapers, our media companies, our colleagues would stand up and demand answers and justice, that our deaths wouldn’t become just another number. Someone would seek justice.

Three years ago as I prepared to celebrate an award from Columbia University—the Maria Moors Cabot prize—I got a call from a trusted U.S. intelligence source who said “I have raw intelligence that says the cartels will kill an American journalist in 24 hours … I think it’s you. Get out of Mexico now.”

I called my U.S and Mexican colleagues who were preparing a celebration dinner for me that evening and said, there’s a death threat and I think we should cancel dinner. Dudley Althaus from the Houston Chronicle insisted, “If they’re going to kill you, he said, they will have to kill us, too. So come on over and have some tequila.” Subsequent solidarity included a protest letter from the U.S. ambassador and editorials in some U.S. newspapers.

My Mexican colleagues can’t say the same thing. They don’t have that kind of solidarity among themselves; they don’t share that trust with their own editors, less so with their own government.

Today, the vast majority of the killings in Mexico, whether you’re a woman in Ciudad Juárez, or a cop, or your average citizen, end up as crimes unsolved, unpunished—“crímenes no resueltos.” More than 95 percent of all crimes in Mexico go unresolved.

I dreamed of being a foreign correspondent not because I wanted to live in some exotic land, but simply because I wanted to return to my homeland. I ached for my roots, language and culture. I often ask myself questions I thought I had finally resolved. Am I what I believe I am? Do I belong to the United States, this powerful country built on principles of rule of law, yet still faced with contradictions—the insatiable appetite for guns, cash and drugs, or do I belong to Mexico, the country of my roots, where my umbilical cord is buried, where we use nationalism and patriotism to more often than not mask our corruption, our poverty and inequality?

The hyphenated complexities of being Mexican-American create a confusing feeling of being in-between. For me personally, this also instills a sense of a higher responsibility to share these stories, especially now when so many reporters have been forced to censor themselves or face death.

As such I strive to understand that when you cover Mexico, particularly the U.S.-Mexico border, nothing is black or white. There are only shades of gray; that to understand these stories you must go deeper, and be able to see and distinguish between shades of gray, understand that not everything is as bad, or good, as it seems.

And that there are always, always, always many sides to this story.

Take for instance, the story of young men who no longer dream of going to the United States to toil in the fields, but who see opportunity in becoming hit men in Mexico, earning as little as 250 to 1500 pesos, the equivalent of $22 a hit to $130 a week. As the old iconic Mexican song from José Alfredo Jiménez, “la vida no vale nada” — life in Mexico is worth nothing.

We’re talking about a whole new generation of children affected—numbed by the daily violence around them and teens from both sides of the border who embrace a new lifestyle and a new saying: “Prefiero vivir cinco años como rey, que 50 años como buey.” I prefer to live five years as a king than 50 as an ox.

Or consider the young Chicano gang member who now uses the same immigration routes his grandparents used decades ago to embrace a new life, a chance at an opportunity. Today, gang members, hand in hand with powerful Mexican cartels, use the same route to distribute drugs in more than 250 U.S. communities where Mexican cartels have an influence. Their role model is a thug from Laredo, Texas, with the name Edgar Valdez Villarreal, better known as La Barbie, a Texas high school football player who rose through the ranks as a hit man to become the most notorious American in a Mexican cartel. The heroes of my time had names like César Chávez, or JFK, or Martin Luther King.

How did things get so bad in Mexico? The answers are complex. Demand for drugs in the U.S., the lure of easy cash, the widespread availability of guns, especially high-powered weapons, smuggled from the United States.

And on the Mexican side it had to do with ignoring a reality: corruption, complicity and greed. For too long, the two countries blamed each other and as they did, Mexico slowly descended into darkness. Corruption grew like a cancer within the government.

Today, Mexico’s conflict is really a war within. It’s about a country trying to redefine itself, become a nation of rule-of-law, but without a clear path, or mandate. Few can question whether President Calderón had any other choice but to take on organized crime, which had reached the upper echelons of power. But whether or not he had the right strategy and the right people is a question that will haunt him, Mexico and us for decades.

The spillover into the United States isn’t so much about violence, but about an exodus of Mexico’s most talented people. And you’re seeing that in enrollment in universities across the country. People migrating today aren’t just nannies, or people picking your blueberries in Maine, or caring for your cows in Vermont or working in restaurants in Boston. No, we’re talking about well-educated professionals, people who used to create jobs—people who now fear being kidnapped, or extorted by criminal gangs.

My biggest concern is that Mexico has yet to reach bottom and nobody yet knows where that bottom is, or what it may look like.

I stumbled onto the story seven years ago when after a brief period at our Washington, D.C. bureau I was assigned a story to investigate who was killing so many women in Juárez. There I discovered the role of organized crime with the help of police in kidnapping and killing some of these women, with no consequences.

After Juárez I discovered Nuevo Laredo, where Americans were also being kidnapped, and a new paramilitary group, the Zetas, members of the Mexican military partly trained by the U.S. government, was terrorizing society.

Suddenly, I was immersed in stories about U.S. agencies mishandling informants, or how U.S.- trained Mexican soldiers had gone rogue, or the deep corruption inside the Mexican government.

I had left Mexico for Washington in 2000, convinced by U.S. officials that the election of an opposition government, the end of 71 years of one party rule, signaled the automatic birth of democratic institutions. Far from it, organized crime took advantage of a power vacuum. With greater ease they bought off entire police forces, politicians, beginning with mayors and local governments. And then they also bought off journalists. The cartels became de-facto governments. It was no longer the threat of plata or plomo, silver or lead. It was our way, or six feet under.

These cartels are very sophisticated about mastering the message. Today, media members serve as spokesmen. Cartel spokespeople will call reporters or editors and dictate what should or shouldn’t be covered in that evening’s newscast, or in tomorrow’s newspaper. Imagine working in a newsroom where you don’t know if your colleague is the brave journalist, or a spy for a cartel.

Last year, El Diario de Juárez asked: what do you want from us? The message was aimed, the editor said, at the drug traffickers. It was a way of expressing their frustration, and sense of impotence of living in the shadow of organized crime.

I’d want to believe that the message was also meant as a wake up call for civil society, because until civil society demands more from wealthy media moguls, journalists will be poorly trained and paid, something that will make them vulnerable to the threats of organized crime.

Earlier this year, Nieman curator Bob Giles wrote a piece of advice that ran in the New York Timeseditorial page:

To the Editor:

The brave journalists reporting on the Mexican drug cartels under the most fearful circumstances should remember a cardinal rule of journalism: no story is worth dying for.

Another friend, and one of the best former Latin American correspondents, Doug Farah, constantly reminds me, “no color is worth dying for.”

I couldn’t agree more with Giles and Farah. Far from preaching that we all be journalistic cowboys, I would argue that we must find a way to find a balance: fear-versus-silence. We must find a way to tell the story, and not let fear be the deciding factor, don’t allow fear to become the ultimate editor who decides whether or not we pursue a story.

Last year, I went to the city of Reynosa, Mexico, with some colleagues to confirm rumors of running gun battles on the streets in broad daylight. We heard parents were keeping their kids home from schools, staying home from work, others were fleeing in droves to Texas.

Because of a media blackout, some were resorting to Twitter, YouTube and Facebook to share news about when it was safe to go outside, or whether to drive down specific streets. The big story on the front pages of newspapers in the area that day? The price of onions going up.

I’m not saying fear is wrong. I actually think feeling fear is a powerful force. Fear is a survival skill. If you’re not scared you become reckless. Fear forces us to stake stock of our lives and reminds us how much life means to us.

So what we cover and how we cover this story is a very personal decision.

I became a 2009 Nieman fellow because I was scared, because I questioned whether what I was doing was the right thing. When I returned to Mexico I felt numb, separated from the story because I realized I didn’t want to put my life on the line anymore.

That sentiment changed on January 31, 2010 when 16 people, most of them teens, were gunned down. When I heard the news that Sunday morning, I felt, like many people, well, they’re probably gang members. So we went to check it out and soon discovered that most were students, athletes, sons and daughters of parents who had dreams for them; parents who told them don’t stray too far from home. Celebrate your friend’s birthday across the street, so you can be close to home.

The hit men were wrongly tipped off that the party was for a group of rival gang members. So they stormed in and lined up and killed 13 of the 36, while friends, or brothers and sisters hid in closets, others hid underneath the bodies of their friends and siblings.

I will never forget the day of the funeral, the sight of a dozen hearses on that street, the sight of coffins, the wailing from parents, friends, brothers and sisters. I’m grateful that it was a rainy day because I felt so angry that I was able to mask my tears with raindrops. And on that sad, gray, rainy morning I broke my silence and found my voice again.

Spring 2013, Volume XII, Number 3

Alfredo Corchado, Mexico City bureau chief for the Dallas Morning News, is a 2010-11 Visiting Fellow at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies and a 2009 Nieman Fellow. He is currently working on a forthcoming book Midnight in Mexico: A Personal Account of My Homeland’s Descent Into Darkness. This article is based on a speech delivered by Alfredo Corchado on receiving the Elijah Lovejoy Award at Colby College.

Related Articles

New Journalists for a New World

I received a surprising phone call one day in late 1993, when I was the director of Telecaribe, a public television channel in Barranquilla, Colombia. The caller was none other than Gabriel García Márquez. “Will you invite me to dinner?” he asked me. “Of course, Gabito,” I…

Latin American Nieman Fellows

A few days after I arrived at Harvard in August 2000 to begin my work as curator of the Nieman Foundation for Journalism, Tim Golden, an investigative reporter for the New York Times in Latin America, phoned me. “Could I find a place in the new Nieman class for a Colombian…

Freedom of Expression in Latin America

In June 1997, Chile’s Supreme Court upheld a ban on the film “The Last Temptation of Christ,” based on a Pinochet-era provision of the country’s constitution. Four years later, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights heard a challenge to this ban and issued a very different…