New directions in Latin American

It was in Amsterdam in the winter of 1978 when I first came into contact with an animal that would later become a monster with multiple heads. It was a time of exile and hundreds of people were literally escaping from the massacre taking place in Argentine and other Latin American countries ruled by military dictatorships. It was a time of struggling for human rights and for building solidarity committees. Coming from an experience of militancy in political parties with a clear ideological identity, the simple idea of sharing a common cause with political rivals was an entirely new feeling. We started to discover that that animal was called a “non-governmental organization”(NGO) and that by linking and networking with other similar animals one could achieve perhaps more than by joining a political party.

Once back in Argentina in 1984 with the democratization process, I realized that a similar phenomenon had also taken place there. Feminists, environmentalists, human rights activists, social developmentalists and neighborhood leaders of various kinds were building organizations to provide an institutional channel for what started as a “movement.” These “new” social movements were quite different from trade unions and parties. They were concentrating on single-issues and looking for changes on a small scale. They were going beyond the traditional boundaries of ideological or labor identity. The NGO animal was already turning into something else, yet without a name.

Some years later in 1988, while sitting at my small desk in a NGO doing research on this new organizational landscape of NGOs, I received a visit. It was not Alexis de Tocqueville but in a sense was talking his same language. Kathleen McCarthy, then and still director of the Center for the Study of Philanthropy at the Graduate School of the City University of New York came to me and offered the chance of a fellowship in New York to study and write about Argentine “philanthropy”. That was the term she used to refer to what I was trying to understand. My confusion was great and it increased when I looked up the term in the dictionary: “love of human kind.” In the brochure about the fellowship program she left on my desk there was some more technical explanation about the meaning of the term: “the giving of time and money for the common good.” All of what I had heard until then about philanthropy was just giving money for the only God. The monster started to take shape.

To cope with the intrigue I accepted the challenge and went to New York. My first day of my first time in Manhattan I attended a course at the New School on “nonprofit management.” After a couple of hours of exercises, my first reaction was to immediately take a flight back home. What does all this talk about boards of trustees, fund-raising, marketing, human resource administration, accountability, missions and visions has to do with the struggle for democracy and human rights? How could I link my previous readings on social movements and social change theory with the guru of modern management Peter Drucker? The many heads of the monster began to emerge. So I decided to stay and grasp the subject deeper.

Once back home, the new Argentine democracy started to tremble due to hyperinflation and the subsequent chaos and popular reactions of looting supermarkets and rioting in the streets. NGOs got organized and started to provide food for the soup kitchens that were springing up all over. They were campaigning and openly asking for donations to buy food but with very little response. Was this philanthropy?

When years later the W.K. Kellogg Foundation invited me to work in the field of philanthropy and volunteerism in Latin America and the Caribbean, my first reaction was positive. Working at a grant-making foundation you can do a lot, I thought. That was a time when there were no apparent signs of local philanthropy in the region beyond the traditional benevolent activities of the rich and the religious charity. Neither were there support systems (university programs, NGO coalition, texts, training programs) to foster its development.

Today the Latin American landscape of philanthropy is quite different. Some facts: there are several university-based research programs and centers on the nonprofit sector; in almost every country, third sector coalitions have been formed, providing a space for NGOs to exchange and share experiences and to advocate for common interests; volunteerism has expanded and specialized volunteer centers have been created; grant-makers associations are emerging; corporate social responsibility concepts and practices are expanding at a fast pace; the media attention to “solidarity” is rising and the participation of civil society in public policies is a common language in politicians and governments; some changes in the regulatory framework of NGOs have contributed to their strengthening.

Why and how was this change achieved? There are a variety of reasons.

The incorporation of nonprofit programs in higher education, both in the social sciences and in business administration, reveals the need of universities to open new career paths in a new field but also a closer connection of universities with civil society issues.

The building of NGO coalitions and umbrella organizations is a response to the perceived weaknesses of isolated actions in the field as well as to the stimuli of international cooperation agencies seeking more effective channels to invest their development dollars in developing countries.

The expansion of volunteerism is associated with the questioning of traditional channels of participation such as political parties and labor unions. This trend also places greater value on the notion of an active citizenship as an essential tool of a vibrant democracy.

The emergence of new private and corporate donors is not only the result of wealth creation but also an expression of the process of globalization with its associated need of stronger and better marketing strategies (i.e. cause-related marketing).

Finally, the increasing relevance of communications and new technologies like the Internet have fostered the inclusion of social and nonprofit/philanthropic issues in the mainstream media, in particular, “good news” about voluntary and community efforts to survive and develop.

In other terms, in a little more than a decade the social and institutional map of Latin America has changed substantially. Not only NGOs and foundations have bloomed but a whole infrastructure to support their activities has been developed. The monster started to walk.

Although the many heads of the monster are now clearly seen, the expected results of the growth of philanthropy are at least contradictory. There are more NGOs combating poverty, but poverty has increased. There are more attempts to increase civic participation in public affairs, but the democracies of the region are being weakened by corruption and economic crisis. There are more sophisticated corporate foundations, but the distribution of wealth continues its unequal path. At a first glance there are no clear signs that more philanthropy means more democracy and less poverty.

When I ask this kind of questions to NGO or foundation officers, there is always a straight and similar answer: “we cannot do it alone, we need the state, we need the business people.” In theory, the model works like this: the third sector provides the expertise to solve social problems and the closeness to the people, the state should transform every single nonprofit action into a public policy, while the business sector should help with dollars and management skills. This approach has a name: partnerships. Based on the assumption that “nobody could do it alone,” the philanthropic system (NGOs, funders, leaders, support systems) is willing to provide the platform for these alliances. From my perspective, this is the main idea behind all the efforts of the philanthropic community in Latin America and the Caribbean. Simple on paper, but very difficult in practice.

As discussed above, the last decade has witnessed the building of an institutional infrastructure for the development of philanthropy and has created an environment favorable to recognize nonprofit activity as an essential part of a democratic system. There is a new legitimacy for actions stemming from private organizations having common good purposes. From a nonprofit perspective the conditions are better than ever to partner with governments and business, but it does not seem that they see the reality the same way. In Latin America, the main purpose of business is still business (and profits! at any cost) beyond the many positive undertakings of social responsibility.

And still the main purpose of governments is governance and economic stability. The quest for partnerships to address the main and many social problems of the region seems far down in their agendas.

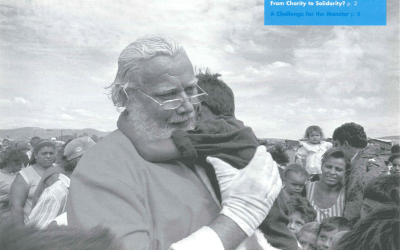

Along with continuous learning and experimentation by nonprofit organizations, the main challenge at this time is to more forcefully advocate the convening of the forces of social change. Increased local giving and expanded volunteerism are good in themselves but insufficient to provoke the desired and needed changes in the distribution of wealth. Stronger voices and leadership are also part of the menu.

The many social movements emerging in the region around crucial issues (landless, anti-corruption, human rights, unemployed, peace, justice) are leading the path towards increased and expanded citizenship. They are even questioning the capacity of the political systems to deliver the minimum welfare for the survival of the large majority of Latin Americans. These forces are the natural allies of the nonprofit and philanthropic community and empowering them may be their best investment in the near future. Will the monster take the challenge?

Spring 2002, Volume I, Number 3

Andres A. Thompson is Argentinean. He joined the W.K. Kellogg Foundation (Battle Creek, MI) as Program Director for Latin American and Caribbean Programs in 1994. He has written and published several books and articles on social development, non-governmental organizations and philanthropy. He is also director of the magazine Tercer Sector and member of the Executive Committee of the Argentine grant-makers association.

Related Articles

Obras de Infraestructura Básica de Fácil Ejecución a través de la Autogestión

En el Ecuador rural y en las zonas citadinas marginales, la carencia de servicios básicos se ha convertido en un mal endémico no resuelto hasta …

Responsabilidad Social Empresarial: Algunos Hechos Que Cuentan

La Responsabilidad Social Corporativa (RSC) es una temática más bien nueva en Chile. Aún cuando se encuentran acciones filantrópicas desde tiempos de la colonia, la relación de la …

Algunos Casos en Chile

Un caso fue José Tomás Urmeneta, un empresario del siglo XIX quien, en un momento de auge del sector agroexportador chileno, en su testamento dejó asignados recursos para …