New Life for the Violin in Mexico’s Hotlands

The Legacy of Juan Reynoso

Once upon a time, the music of Tierra Caliente was hidden treasure—wild and charismatic violin melodies lifted up by guitar chords, rooted in driving bass runs, and punctuated by varied sounds of a little drum called tamborita. The few who knew about Tierra Caliente’s sones and gustos—people living in other parts of Mexico—coveted recordings of a remarkably talented violinist, Juan Reynoso. They shared these rare possessions with awe-struck friends and then lamented, “You’ll never hear him live; he’s no longer with us.”

Fortunately, I never heard those rumors before I decided to track down the musician I had discovered on a cassette in a Mexico City music store in 1993. After listening repeatedly to “El gusto federal,” “La malagueña de Guerrero” and “La tortolita,” I invited a friend to go to Ciudad Altamirano, Guerrero, to see if we could find the magnificent musician who played those Tierra Caliente classics. To our delight, we spent an entire day with don Juan. He was very much alive.

We found his little blue house in the nearby dusty village of Riva Palacio, Michoacán, seven hours southwest of Mexico City, though the drive had taken us much longer than that. Although we left Mexico City about midday, we had to stop once it got dark, and we didn’t pull in to Altamirano until the next morning. Esperanza, his wife and the mother of ten, told us about her husband’s three marriages and his numerous children—more than two dozen if you count those out of wedlock—while we waited for him to finish his morning shower.

“I play yesterday’s music,” he told us, when he emerged. He didn’t know he had fans far away who thought he had passed away, or that within a couple of years he’d have many more admirers in the United States as well as Mexico, or that in 1997, the President of Mexico would hand him the country’s highest award for an artist, the Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes.

But before he could become well known again in Mexico, he became recognized internationally. Through my musical contacts, I arranged for Don Juan to perform at the 20th Annual Festival of American Fiddle Tunes in Port Townsend, Washington, in 1996. The standing ovation he received from U.S. musicians led to a standing invitation to the Port Townsend week-long workshop featuring many traditional fiddle styles.

I had only planned to travel with him that once in 1996. However, I soon fell into being his festival escort-translator-assistant year after year, slowly leaving behind my career as a business journalist.

Don Juan returned to the festival as long as he was able, finally canceling his tenth appearance just before what would have been a difficult journey in 2005. For the Reynosos, going to the festival meant a seven-hour bus ride, an overnight in Mexico City, two flights which together took seven or eight hours not counting the layover, and finally a two-hour car ride.

Accompanying him each time he taught and performed in Port Townsend, I was inspired to launch an annual festival in Mexico that featured don Juan and other traditional musicians from Mexico, the United States and Canada. That festival, the Encuentro de Dos Tradiciones, lasted eight years, from 1997 to 2004.

I also began booking Juan Reynoso’s performances elsewhere and serving as his media contact. The BBC as well as Mexico City papers contacted me. In addition, filmmakers Pacho Lane and Marcia Perskie produced hour-long documentaries titled, respectively, Viva mi Tierra Caliente and Looking for Don Juan.

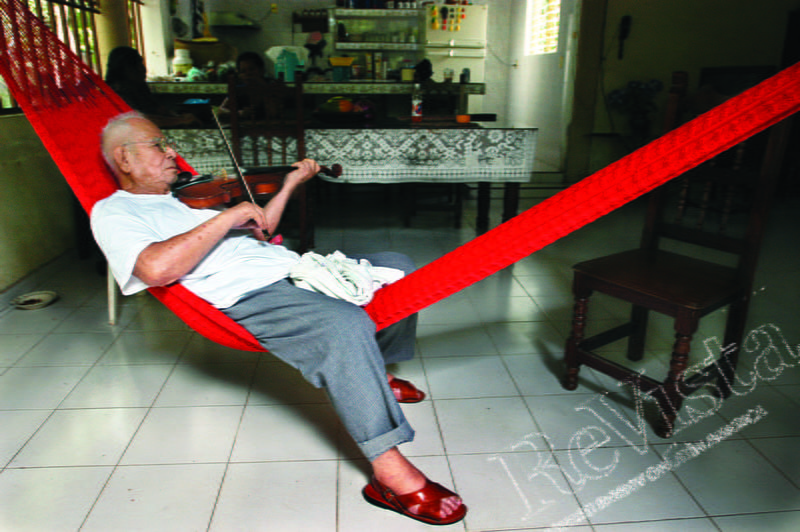

I had never imagined that a casual encounter with a cassette would make such a profound change in both my life and don Juan’s. I still remember so well that first day with him. Even at 80 years old, he didn’t seem to tire, playing music and telling stories about his life throughout the entire day. Occasionally he’d pick up a red bandana and wipe beads of sweat from his brow. Otherwise, the heat didn’t seem to bother him. Nothing was more important than the music. He played fast, he played slow—depending on the melody—but always with precision. Thick fingers, large hands; double stops; always in tune.

I learned that he was born in Ancón de Santo Domingo, a dusty village above Coyuca de Catalán, on a hot summer day in 1912. Juan’s birthplace was in Michoacán at the time, but a shift in state lines later made it part of Guerrero state. The largest nearby “city” would have been Pungarabato, a unpaved town that eventually changed its Tarascan name to Ciudad Altamirano to honor a 19th-century Supreme Court president and writer born near Guerrero’s state capital. It was two years into the Mexican Revolution when Juan entered the world, while his parents Felipe Reynoso and Luisa Portillo were struggling to survive in a remote area during that tumultuous era.

In the midst of the decade-long Revolution, the elder Reynoso worked hard to scratch out a living. Juan remembers begging his dad for a violin and hearing him reply, “whatever for?”

“Even a little guitar would do,” Juan countered.

Over the years, Juan repeated an anecdote about getting his first violin thanks to an orphan boy staying with his family. The boy stole a little instrument from the market but didn’t play it much. Juan toyed around, exploring the sounds a plastic bow made on four strings until he could scratch out familiar melodies. Later, he said the story wasn’t true. It doesn’t really matter how he got that first violin, or any of the subsequent ones. It doesn’t even matter that he thought the ordinary fiddle he played when I met him was a Stradivarius. What matters is that in his hands, any instrument made powerful, beautiful music. The great composer Bardomiano Flores, much older than Juan, once gave him an instrument. According to Juan, there had been some rivalry, but the gift put that to rest. Tierra Caliente musicians are fiercely competitive and jealous. But the struggle to be king of the mountain is also fertile ground for lifelong friendships.

Juan Reynoso relaxes as he plays his violin in a red hammock. Photo by Chris Vail (www.chrisvail.com).

During the 1940s, Juan lived in Mexico City, performing regularly on the radio. In the 1970s, he was among the musicians immortalized when three young men traveled throughout Mexico to make field recordings of regional music. One later created a record company, Discos Corason, which eventually released their Antología del Son Mexicano as phonograph records, then cassettes, and finally CDs. That collection, as well as an LP record issued by the University of Guerrero, and homemade tapes made by one of Juan’s compadres, introduced the “Paganini de Tierra Caliente” to many of his future fans.

His coke-bottle glasses might have given a different impression, but even as an octogenarian don Juan was alert to the world around him. He noticed when a guitar string was barely out of tune from across the room. He recognized people from across a busy street. And his memory for melodies he hadn’t played or heard in half a century was precise even though he was unable to read written music.

After I left Mexico, Andrés Jaimes from the town of Tlapehuala wrote a song—“Linda Paloma”—about how I had come to Tierra Caliente and become involved with the music. By then, the festivals were over and the premature rumors of the great violinist’s death became real in January 2007, when he passed away. Jaimes’ song had a melancholic line: Oye Lindajoy, ya no está Juanito, solo sus notas, sonando bonito. (Listen, Lindajoy, Juanito is no longer here, just his notes, sounding beautiful.) But the song is joyful because it explains that the music of Tierra Caliente is alive and well.

Llegaste un día removiendo de retardo

la inspiración ancestral de mi pueblo.

Uniste eslabones para que cada mañana

se despertara con violines y guitarras

You arrived one day, belatedly stirring up

the ancestral inspiration of my people.

You connected the links so that every day

we would wake with violins and guitars

Indeed. Tierra Caliente does wake up to the sounds of violins and acoustic guitars more frequently. Tierra Caliente sounds are in far better health than when I first happened across them and found that the only people playing traditional violin music were in their 70s, 80s and 90s. Even though some people there still prefer more modern styles with electronic instruments, in other circles the traditional music don Juan thought had faded into obscurity is coming back into its own.

A group of young people in their teens and twenties—who call themselves Los Nietos de don Juan though not related to him—play his music in the town of Arcelia. Little music schools have sprung up in Zirandaro, Tlapehuala, Altamirano and other Tierra Caliente towns. And an annual summer camp for children in the region brings the music alive with instrument and dance lessons. Los Jilgueros del Huerto—perhaps the best representatives of promising, young calentana talent, and key participants in the summer workshops—followed in Reynoso’s footsteps when they performed at the Festival of American Fiddle Tunes in 2013. When I organized my last event in Mexico, these young musicians had performed on the same stage in Morelia, Michoacán, with the master when they weren’t yet teenagers. Another top calentanofiddler, Serafín Ibarra, a lifelong fan of Juan Reynoso who learned the musical style from his own great-uncles, continues to perform and teach Tierra Caliente music. He is one of the very few who can play the difficult jarabes in this style as well as sones, gustos, pasodobles and waltzes. Ibarra has released over a dozen recordings with his group, Los Carácuaros, and is soon to release one with Jesús Peredo reproducing the violin and guitar work of Juan Reynoso and Salomón Trujillo. The blind Trujillo was perhaps Juan’s favorite guitarist. Another favorite was his son Maxímino. Unfortunately, both had died long before I went to Tierra Caliente.

When I first met don Juan and the other older fiddlers, I rarely saw people dance to the music they played. Ironically, now that most of the old men are gone, the music they feared might die with them has revived amongst the young people who dance as well as play sones and gustos calentanos.

Juan remembered the strong steps of the zapateado that allow the dancers to become a percussive part of the music. But in the last years of his life he played in cantinas or at concerts where his audiences were sitting down. Although the environment might have been more festive in his earlier years, quiet audiences suited don Juan just fine. He told Raquel Paraiso, a Spanish academic at the University of Wisconsin who focused her post-graduate ethnomusicology research on don Juan, that he didn’t want people to dance because it took attention away from the music. “He wanted people to listen,” she said. “Incredible, such a strong character he had.”

Paul Anastasio, one of the many American fiddlers captivated by Reynoso at the Festival of American Fiddle Tunes, also attended every Encuentro de Dos Tradiciones festival except the first. He studied under don Juan for the rest of the master’s life, earning his approval as a musician, transcriber and arranger. He now writes in the style of his teacher and uploads videos of Juan Reynoso to a YouTube channel.

Today, Tierra Caliente is hot. Not just because of its blazing sun. Not just because of its driving music. Violence and illegal drug activity have created an environment where it is highly unlikely that a foreigner like me would hang out with local musicians and organize festivals.

The music of Tierra Caliente, however, is now safe in the hands of local youth whose love for it exceeds any interest in money or drugs. With the music schools popping up in small towns, more people breathe life into the tradition by singing, playing, and partying. And, as my friend Zarina Palafox, who became part of the Dos Tradiciones festival as well as the Mexican government’s now dormant Tierra Caliente program, likes to say, “When a young person has a violin in one hand and a bow in the other, there’s no place for a gun.”

Winter 2016, Volume XV, Number 2

Lindajoy Fenley went to Mexico in 1988 as a journalist. After meeting Juan Reynoso, she began promoting music and culture, organizing festivals in Tierra Caliente. She returned to the United States in 2006 and continues to work with musicians from many countries in Arts Midwest programs.

Related Articles

Beyond Bolaño: The Global Latin American Novel

I often wonder what life would have held for the late Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño if he had not passed away due to liver complications more than a decade ago. This year he would have…

Notes on Mexican Rock

English + Español

Since the 1960s, there’s been a booming underground rock scene in Mexico. It defines itself as countercultural, but not in absolute opposition to the mainstream—although sometimes it…

Nature’s Sonorous Politics

English + Español

There’s no indigenous political movement in Andean Peru. This, at least, has been the consensus view of scholars since the 1990s, when protests organized by indigenous parties shook the…