New Takes on the “New”

The Cinemas of 1960s Latin America

To judge by the proliferation of Latin American films on the international festival circuit these days—not to mention the colossal box-office success of works by Walter Salles (Motorcyle Diaries), Fernando Meirelles (City of God), and Guillermo del Toro (Pan’s Labyrinth), among others—Latin American cinema would appear to be very much on the rise at the end of this first decade of the new millennium. Yet, while we celebrate its resurgence, an irresistible historical serendipity also finds us marking the fortieth anniversary of May 1968, along with all the gilded cinematic memories that mythical year evokes. After all, if film history has enshrined “The Sixties” in the aura of so many New Waves—think France, Czechoslovakia, India, and Japan—it should also recall that long decade (which arguably extends from the late 50s to the early 70s) as the last great moment of renovation in Latin American cinema as well.

To be sure, scholars, critics and filmmakers have long since formulated a rather monolithic conception of the so-called New Latin American Cinema (NLAC) of the 1960s, a tag that suggests a coherent, pan-continental, aesthetic movement rooted in political militancy, formal innovation and independent modes of production intended to counter the Hollywood industrial model. The NLAC rubric has served to encompass the works of artists as disparate as Tomás Gutiérrez Alea (Cuba), Jorge Sanjinés (Bolivia) and Pino Solanas (Argentina). It has implied a set of precursors both external (Roberto Rossellini, Cesare Zavattini) and internal (Leopoldo Torre Nilsson); designated its founding fathers (Fernando Birri; Nelson Pereira dos Santos; Julio García Espinosa); anthologized its manifestos (with cries for an “Imperfect Cinema” or a “Nationalist, Realist, Critical and Popular Cinema”); and even anointed its high priest, long gray beard and all (Fernando Birri again). In fact, most written film histories to date have adhered either directly or inadvertently to the NLAC model, which has been useful not only in constructing the canon of films we watch, teach and study to this day, but in organizing the manner in which we talk about Latin American films from the period more generally.

The 60s undoubtedly spawned a cascade of activity and experimentation in independent film in Latin America. Yet I wonder whether the NLAC paradigm—the concept of Latin American cinema from the mid-50s to the mid-70s as a verifiable, even quantifiable “movement”—hasn’t led us to close the book on a still unfinished chapter of film history.

The contrasting stories of Brazilian and Argentine art cinema from the period are reason enough to treat the conventional account of the so-called New Latin American Cinema with skepticism. Brazil’s Cinema Novo was often bolstered by state incentives for domestic film productions, even in an atmosphere of acute government censorship. Indeed, the Brazilian movement probably constituted an aesthetic program far more coherent than any broader notion of the NLAC. Irrespective of the profusion and variety of individual expressions—and these were legion, to be sure—the cinemanovistas seemed genuinely united around the ideal of a highly individualistic, modernist art form that was also unflinchingly militant in its engagement with local socio-political issues (national identity, neo-colonialism, underdevelopment). It was precisely this synthesis of aesthetic self-expression and political activism that Glauber Rocha succinctly encapsulated in his 1965 manifesto, “Estética da Fome.”

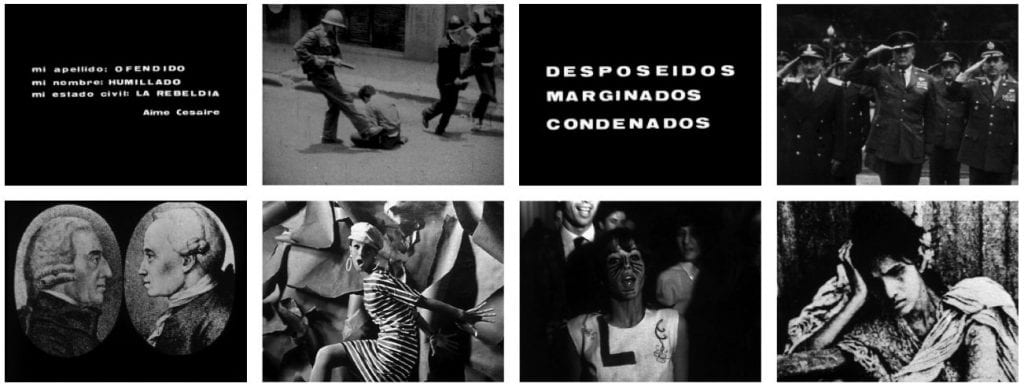

Such a synthesis, however, was much less characteristic of Argentina’s Nueva ola, another Latin American “new wave” that produced many largely undervalued masterpieces. From Leonardo Favio to Nicolás Sarquís, from Hugo Santiago to Juan José Jusid or Alberto Fischerman, the directors of this new generation produced works far less overtly obsessed with questions of national identity, though certainly as “modernist” as their counterparts from Brazil. Thus, the Argentine films most frequently associated with the canon of the NLAC are often the least “typical” of Argentine cinema from the period. To wit, Pino Solanas and Octavio Getino’s La hora de los hornos (1969) may certainly stand as the founding work of “Third Cinema.” Yet its radical sound track and barrage of agitprop slogans flashing in big, bold-face letters between swarms of appropriated images—closer to the militant films of French activist Guy Debord than to other works of Argentine national cinema—produced few imitators beyond the members of its own Grupo Cine Liberación [Fig. 1]. The same might be said of Fernando Birri, the aforementioned “pope” of the NLAC. Though he did establish the legendary Escuela de Cine Documental de Santa Fe, with its orthodox neo-realist agenda, it would be difficult, in hindsight, to list the adherents to any kind of “movimiento birriano” within or beyond Argentina.

Invaluable as the NLAC model has been to our understanding of Latin American cinema from the mid-50s to the mid-70s, I fear that we have grown complacent with its convenience. As a result, we may risk relegating inexhaustibly complex films from the period to the backwaters of retrospectives, encyclopedias and festival catalogues while missing the opportunity to refresh our understanding of these works, or even to open the Latin American film canon to new efforts of preservation and dissemination. Hence, I’d like to propose just a few of the areas toward which the future promotion of 1960s Latin American cinema might migrate. My hope is that we not only reconsider the films we know well, but point the way toward lesser-known films worthy of attention. While my focus will hew closely to the cinemas of Argentina and Brazil—the two areas of Latin American film I know best—I believe my prescriptions apply just as well to movies and directors from across the Americas.

On Film Form And Politics

The political content of 1960s Latin American cinema has perennially defined our appraisal of individual works from the period. Nonetheless, we are far from penetrating the varied, complex formal mechanisms of their political critique. This is a shame, because on the whole, much of the NLAC’s own canon is rich in formal idiosyncrasies deserving of greater attention. Take Fernando Birri’s Tire dié, from 1958, the work held up by many as the keystone of new cinema in the Latin American 60s. The film’s social commentary may seem self-evident, so much so that theoretical analyses rarely move beyond its most famous sequence, in which impoverished children from the outskirts of Santa Fe, Argentina, race alongside a train rolling across an elevated causeway, shouting to the passengers to “Throw a dime!” [Fig. 2]. Yet, while the montage may at first glance remind us of Eisenstein (so goes the prevailing assessment), the real impact of the sequence resides in its peculiar use of overlapping editing and the consequent effects on cinematic time and space. What’s more, the film brims with noteworthy formal quirks, among them a seemingly inadvertent repetition of graphic elements from one segment of the documentary to the next [Fig. 3]. Consciously or unconsciously, the design of the film points up a confrontation with received ideas about the nature of modern space at the dawn of the 60s, one that I believe exists in other works throughout the decade, both in Latin America and beyond.

On The Uses And Misuses of Genre

Just as new wave directors elsewhere mined American film genres to stage a wholesale renovation of the cinematic medium (Jean-Luc Godard comes immediately to mind, of course, but so does Seijun Suzuki, whose 1967 film, Branded to Kill, is a ribald send-up of the gangster film), in Latin America, too, filmmakers in the 60s turned a critical eye toward genre and its received protocols. Indeed, examining the uses, abuses, and creative misuses of Hollywood genres may be one good way to expand the canon of 1960s Latin American cinema. In Brazil, for instance, a considerable amount has been written about, say, Glauber Rocha’s take on the Western, or Joaquim Pedro de Andrade’s version of the road movie. Less familiar, though, are the works of Cinema Marginal, a Brazilian underground movement of the period in which the irreverent deconstruction of Hollywood genres formed the crux of its innovation. I’m thinking not only of the group’s hallmark work, O bandido da luz vermelha (Rogério Sganzerla,1969), but of lesser known films like Bang Bang! (1971) by Andrea Tonacci (which Ismail Xavier discusses at the end of his seminal book, Allegories of Underdevelopment) [Fig. 4]. There, Tonacci makes mincemeat not only of the Western, but also the crime thriller, film noir, the “city symphony film” of the early 1920s, and even the science fiction B-movie. Similar palimpsests reside beneath Júlio Bressane’s Matou à família e foi ao cinema and O Anjo nasceu, both shot in 1969.

In Argentina, meanwhile, many important films from the 60s and 70s buried in the archives today could be revived by attending to their treatment of genre: film noir in Lautaro Murúa’s Aliás Gardelito (1961); film noir mixed with science fiction in Hugo Santiago’s Invasión (1969) [Fig. 5]; the gothic in Leonardo Favio’s El dependiente (1968); the coming-of-age drama, from Rodolfo Kuhn’s Los jóvenes viejos (1961) to Favio’s Crónica de un niño solo (1966) to Murúa’s rarely screenedLa Raulito (1975). All these works, to one degree or another, are concerned with the subversive recycling of genre conventions, to great formal and political effect.

On Film-Theorizing And The Concept of “New Wave”

Finally, what we know today about Latin American cinema in the 60s suffers from a curious theoretical reticence when compared to our appreciation of other film “new waves” of the period. This need not be the case, though I hardly mean to suggest that a renewed approach to Latin American cinema from the 1960s must somehow resuscitate the many film theories to emerge in the period (film semiotics; auteur theory; Lacanian film analysis). Rather, I call for new theoretical strategies to resurrect and reevaluate old films. My own work on Argentine and Brazilian cinema, for example, has led me to reconsider the largely unquestioned link between our ideas of “modernity” and our assumptions about its inherently urban nature. Films like Godard’s Alphaville or Jacques Tati’s Playtime may lead us to draw certain conclusions about the city as synonymous with modern space, and thus about the ways that modern space conditions knowledge in the 60s. Yet those notions acquire new hues of meaning when re-examined in the light of films like Favio’s El dependiente or Paulo César Saraceni’s Porto das Caixas (1963) [Fig. 6], both set in provincial towns neither fully urban nor entirely rural.

While issues of national or regional identity, allegories of underdevelopment, neo-colonial resistance and post-colonial revolution have dominated the way we think about Latin American cinema, to push beyond them toward larger philosophical questions of time, space, knowledge, and phenomena can inject new energy into the critique of Latin American films from the 60s, and even enhance our understanding of that decade’s global profusion of film new waves.

Unquestionably, independent cinema in the Latin American sixties was always a part of something much broader. In my view, the arch-movement of the NLAC may have been a scholarly invention more than any truly self-conscious aesthetic agenda. Yet the many pioneering movies from the period—canonical and otherwise—are more than national artifacts or political documents. Certainly, they are more than mere objects of unilateral influence from the many historical film movements of the “center” (Italian Neorealism, French New Wave) to the single, idealized Movement of the “periphery” (NLAC). To grasp the legacy of 1960s Latin American cinema today—and even ensure its posterity—perhaps the time is ripe to liberate these works from the static framework of an avant-garde program that may never have been. So many challenging films from the Latin American 60s beg to tell us not where they fit within the New Latin American Cinema, but just what about them was so essentially “new” and “cinematic” within the broader context of film new waves the world over.

Looking Ahead

Will the dawn of the 21st century be remembered as the Renaissance of Latin American cinema? Hollywood might have us think so, given its backing of a number of international blockbusters by Brazilian directors like Walter Salles (The Motorcycle Diaries) and Fernando Meirelles (The Constant Gardener), or those of the Mexican triumvirate of Alfonso Cuarón (Children of Men), Guillermo del Toro (the Hellboy franchise), or Alejandro González Iñárritu (Babel).

Yet film productions of the art house variety—arguably a better index of healthy cinema culture beyond Hollywood—are also burgeoning across the Latin American continents. Argentina sent two young directors to compete at Cannes this year (Lucrecia Martel with La mujer sin cabeza and Pablo Trapero with Leonera), only a year after Mexican director Carlos Reygadas won the jury prize there for Stellet Licht. Colombia’s film industry has been so fertile, meanwhile, that this year’s Los Angeles Latino International Film Festival ventured to screen an impressive seven of its latest features. Elsewhere, Chilean works like El cielo, la tierra y la lluvia, by José Luis Torres Leiva, are garnering accolades and prestigious awards from L.A. to Rotterdam on the international festival circuit. And at the most recent edition of Bafici (the Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema), perhaps the most esteemed film festival in the Americas, Mexico’s Yulene Olaizola bested competitors from around the world for her documentary, Intimidades de Shakespeare y Victor Hugo.

Related Articles

Revolution by Osmosis: A 60s Remembrance

I grew up in the peaceful paradise of Costa Rica. I can picture myself as a 13-year-old in 1960, a rebellious teenager with little self-esteem growing up in the exuberant tropical landscape surrounded by mountains, volcanoes and the sea. The big commotions of the 1960s that would shake the world did not reach us. The first tremors that heralded in the Cuban revolution, student movements, Vietnam and the feminist movement …

Between Bombs and Bombshells: Students and Sexual Politics in 1968 Brazil

Of the many dynamic political and cultural forces that marked Brazil in the 1960s, one of the most remarkable was the effervescent student movement, especially during the momentous year of 1968. University students in Brazil had a long history of organizing politically and participating in national issues. However, the student movement of 1968 was unlike its predecessors. It represented some of the intense transformations…

From Selma to Salvador: African-American Echoes in the Brazilian Movimiento Negro

When James Brown released “Say It Loud: I’m Black and I’m Proud” in 1969, little did he know that his music, his swagger, and his style would play a prominent role in Brazilian blacks’ struggle for self-affirmation.

Brown certainly wasn’t the sole catalyst of the Brazilian movimento negro, which has yet to experience a large-scale, organized black movement as the United States did in the 1960s. Yet, Brazil—the country with …