Our Disappeared/Nuestros Desaparecidos

The Act of Memory

Memory has a way of finding its way into the present through small cracks. Ruins of an ancient city, a sign on a street or a poem can keep the past in the present.

One evening about eight years ago I was wondering what had become of Patricia Dixon, a girlfriend of mine in 1973. We had met at the Sociology Department at the Universidad de Buenos Aires, at a time when the school was a recruitment place for revolutionary organizations. Juan Domingo Perón was in the process of returning to power after 18 years of exile, and many in my generation had expectations that he would lead to deep structural changes in Argentine society.

Patricia was a beautiful petite brunette, full of energy and humor. Strangely, in all the years up to that moment I had not thought of looking her up. When I googled her name I expected to find that she had become a teacher or a psychologist. Instead I was shocked to find her name on a list of people who had disappeared during the dark years of the 1976-1983 military dictatorship. She was taken from her home in the early hours of September 5, 1977, and never seen again.

In March 2005 I went to Buenos Aires to try to find out more about Patricia’s fate. A friend helped me locate her file, which included her sister Alejandra’s deposition from 1984. In one of the many small miracles of this story, Alejandra was still listed in the phone book, 21 years later! I called with a certain hesitation, not quite knowing what to say. But when Ale picked up her reaction was: “Ohhhh…” She knew exactly who I was: that young man who had dated her sister, who was eight years older. It was almost as if she had been waiting for my call. All those years she had kept a photograph that I had taken of Patricia by her bedside.

That was the beginning of a profound creative and life experience that led to my making a feature-length documentary film, Our Disappeared/Nuestros Desaparecidos, that explores what happened to Patricia and to other people I knew who disappeared during that reign of terror.

The film aired on the PBS series “Independent Lens” in 2008 and “Global Voices” in 2011 and played at more than thirty festivals worldwide. Audiences from India to Colombia to New Zealand have related to the universality of the stories. At the Mumbai International Film Festival there was no discussion period after the screening, so I waited outside the theatre to meet viewers and chat with them. A number of people came forward to greet me, held my hands while looking me in the eye, and moved on, not saying a word. An Indian friend told me that this was a sign of deep respect. At the Docúpolis Festival in Barcelona, several Argentine exiles in the audience found ties to the stories I tell in the film—a former boyfriend, a compañero in a revolutionary organization, the mother of a close friend. When I present the film at colleges and universities, students connect with the deep commitment held by young people who were their own age. They ask probing questions and write thoughtful papers about the film and this dark period in Argentine history.

Since the film was finished in 2008, the judicial process in Argentina has made great advances and hundreds of cases have been reopened: 250 perpetrators have already been convicted. Every day there is a new case in the newspapers. Julio Simón, a.k.a. “Turco Julián” (a former secret detention-center guard who appears in the film bragging in 1995 about torturing and killing militants), was sentenced to 25 years in prison. Former junta leader and President Jorge Rafael Videla recently died in jail, unrepentant. He was sentenced for the theft of 34 babies and other crimes. Unfortunately one of the most sinister characters, Admiral Emilio Massera, became senile and died unpunished. Many other criminals are going to their graves with their secrets unrevealed.

Of the more than 500 babies who were kidnapped or born in captivity, 108 have been identified and reunited with their natural families, thanks to the relentless work of the Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo, the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo.

The children of the disappeared whose stories I tell in my film could have all been stolen. Two of them were taken with their parents but later returned to the families. One of the most powerful developments is that now they are all parents themselves. Juan Manuel Weisz had Marcelo, the baby who appears in the film. Natalia Chinetti had a baby girl. Antonio Belaustegui has a baby boy. Tania Weisberg had twins two years ago. And on September 5th of this year, on the anniversary of Patricia’s disappearance, Ines Kuperschmit gave birth to her third boy. As Juan Manuel says in the film, “Life wins in the end.”

A movement in the city of Buenos Aires is slowly creating a very particular memorial space for the disappeared. Barrios por la Memoria, “Neighborhoods for Memory,” helps families and friends of the desaparecidos fabricate and lay tiles, baldosas, near where they lived, worked or from where they were taken. In March 2012 we laid one in Patricia’s memory in front of the building from where she was kidnapped. There was music and dancing. Family, childhood neighbors, friends and work colleagues recalled stories that reflected her beautiful soul. Everyone present felt that the act of laying the tile and remembering Patricia in this deeply felt way had been very healing. It became the memorial service she had never had.

There have been a surprising number of “coincidences” during the making of the film and since. In preparation for making Patricia’s tile, Alejandra and I met with two people from the group Barrios. Ale suggested that they see my film, but asked them not to copy it because an older woman who appears in the film still harbors some fears and doesn’t want the film widely distributed in Argentina. Mauro Rapuano, one of the organizers, asked her name. “Ruth Weisz,” I replied. His face went white. He had been the best man at her disappeared son’s wedding!

For many years the disappeared have been remembered on the day of their vanishing with remembrance ads in the Buenos Aires newspaper Página 12. On the 15th anniversary of Patricia’s disappearance Alejandra wrote a poem, and enclosed the photo I had taken. The last lines of the poem read, almost in a premonition:

“Duerme en medio del naufragio y sueña que se despierta en el corazón de un hombre que se sacude la pena”

“She sleeps amidst the shipwreck and dreams that she awakens in the heart of a man who sheds his sorrow.”

Patricia has awakened in my heart and in the hearts of all who have come across her story. Patricia and the thousands of others who were taken are nuestros desaparecidos, our disappeared, and we have a duty to always remember them.

Related Articles

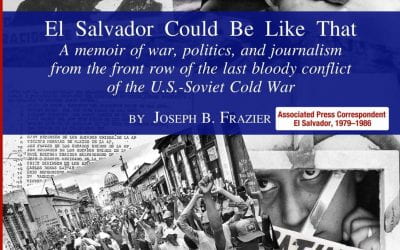

El Salvador Could Be Like That: A Memoir of War, Politics, and Journalism from the Front Row of the Last Bloody Conflict of the U.S.-Soviet Cold War

“There are no just wars. There are only just causes.” I was sitting in the modest home of a former FMLN guerrilla woman in a rural village in the northeastern corner of El Salvador. It was 2001, and I was nearing the end of my second year-long stint in this small Central American nation, interviewing more than 200 Salvadorans, mostly from rural areas, about their experiences during the civil conflict of the 1980s. …

First Take: Memories and Their Consequences

I visited the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos in Santiago, Chile, two years ago. It was a heart-rending experience. To enter the museum, I moved through a stark and subterranean passage and found myself in a somber space of transition. There, a wall of photographs transported me back in time—long ago in a messy graduate student lounge in Cambridge, Massachusetts, four of us stood in shock …

An Exploration of the Mexican Health Care System

The recent creation of Seguro Popular—a governmental program granting basic health services to millions of Mexicans previously uninsured—has newly enabled thousands of Mexican women afflicted with breast cancer to access treatment. With the growing prevalence of breast cancer survivors, the question now arises of how best to maintain their health and address their needs. …