Pain on the Border

Fieldnotes from a Migrant Aid Center in Nogales, Mexico

Not a single seat is left in the humble dining hall decorated with murals of campesinos harvesting corn in the fields. Above rows of wooden tables ceiling fans spin frantically, failing to disperse hot summer air. Except when they raise their hands to ask for more “agua”—a muddy brownish drink of water with oatmeal—the men eat their breakfast quietly. There are women too, but they sit at a separate table in the back, where the image on the wall portrays Jesus and the Apostles at the Last Supper. Some are here with children. At least one is pregnant. Today’s meal consists of eggs with spinach, rice and beans. Visible through the gap under the tin roof covering this soup kitchen is a green sign with an arrow announcing FRONTERA USA.

This comedor was started by the Missionary Sisters of the Eucharist before it became part of the Kino Border Initiative, a binational humanitarian effort named after a Jesuit who spent his life in the Sonoran Desert before a Mexico and a United States—and a boundary between them —even existed. Twice a day, with the help of volunteers, the nuns prepare hot meals to migrants who have been deported and separated from their families as well as those who are en route to el norte, fleeing violence, economic turmoil and natural disasters. The comedor is where the displaced meet. Last year alone the sisters served more than 42,000 meals.

The comedor is more than a soup kitchen. I first came to this aid center for migrants in June 2015. While doing field research for my new book about emergency responders along the U.S.-Mexico border, I volunteered as a paramedic with the Nogales Suburban Fire District and with the Tucson Samaritans. The Samaritans, appalled by the militarization of the border and the suffering of migrants it has caused, have been going out into the desert to look for those who may be hurt. They leave bottled water on popular trails in remote canyons. They roam the desert in SUVs carrying first-aid kits. They install crosses at death sites. They pick up the trash –– empty cans and wrapping paper discarded by those forced to travel light. They collect socks and blankets for the shelters in Mexico. Taking turns with the volunteers from No More Deaths, another humanitarian organization committed to stopping the deaths and abuse of migrants in southern Arizona, they bring cell phones to the comedor so that migrants and deportees could call family members in the United States or in Latin America, free of charge. Samaritan nurses and doctors, mostly retired, provide medical aid to the sick and injured. That’s how I got involved. This was my first day.

Some of the people at the comedor have spent weeks or even months traveling north on foot, by bus and on top of notorious crowded freight trains—there are good reasons why they call them la Bestia (the beast). They came from central and southern Mexico, Honduras and other parts of Latin America. This is their last rest stop before they try to cross. Though they carry backpacks, their jeans and tennis shoes are better suited for a walk in a city park than a strenuous hike across the hostile terrain of the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, where everyone and everything conspires to kill trespassers: a blister or a sprained ankle could be a death sentence if the injured can’t walk fast to keep up with the group or if the guide decides to abandon them. More than 2,500 human remains have been found in southern Arizona since 2001. Dehydration and heatstroke are common culprits. Nature here is incompatible with human life.

Many already know about the mortal dangers awaiting migrants in the desert. They also know about the cages mounted on the beds of the Border Patrol trucks, custom-made to be uncomfortable—during rough rides on unpaved roads the captives bang their heads into the roof. Transparent bags with their names and their meager belongings that some deportees have brought to the comedor are tokens of their encounter with la migra, a reminder of their time in detention. Between July 2014 and March 2015 more than one-third of 7,500 migrants who participated in the survey at the comedor reported abuse or mistreatment by U.S. authorities, including inhumane detention conditions, verbal abuse, racial slurs, physical assaults. When they are apprehended and deported, migrants are frequently separated from immediate family members and travel companions. Left without anyone they can trust, they are more susceptible to attacks and robbery in Mexico.

Here at the comedor, the heat is already suffocating at nine o’clock in the morning. Sarah and I sit by the shelf with medical supplies. Tags on transparent plastic boxes identify the contents: “feet,” “wounds,” “pain,” “skin,” “allergies,”“blood pressure,” “diabetes,” “stomach,” “eyes,” “gauze,” “ointments.” Sarah is training to be a nurse. She does not speak Spanish. Some deportees talk to us in English, but I conduct patient interviews with the rest in Spanish and translate. We clean infected wounds and advise how to treat blisters. We send most people away with a few doses of ibuprofen and over-the-counter cold remedies. It’s as much as we can do, even though we know that pills, cough drops, ointments and gauze only deal with signs and symptoms. Since we can’t treat the political and economic conditions that have forced people to leave their home and put them in harm’s way, we can only supply a temporary medical solution to cover up injuries of violent displacements.

A young man leans towards me and talks in a hushed voice. He shows me a bottle with prescription medications. “I have HIV,” he says. The pills are antiretrovirals. Since he does not have a local address in Nogales, the doctors at the hospital could only give him one month’s supply. In Acapulco, Guerrero, where he is from, four encapuchados (men wearing masks) forced his father into a car and decapitated him. He is not going back. One of the volunteers is going to help him file for asylum.

A former military man from Central America complains of lingering pain in his feet. He jumped off the train when the pandilleros—gang members—tried to rob him and injured both legs. He never saw a doctor. He says he can manage the lingering pain with pills, and he is not giving up on his plan to cross the border. In the military, he tells us, he learned how to navigate the desert, how to use a compass. He is sure he can make it. We give him ibuprofen.

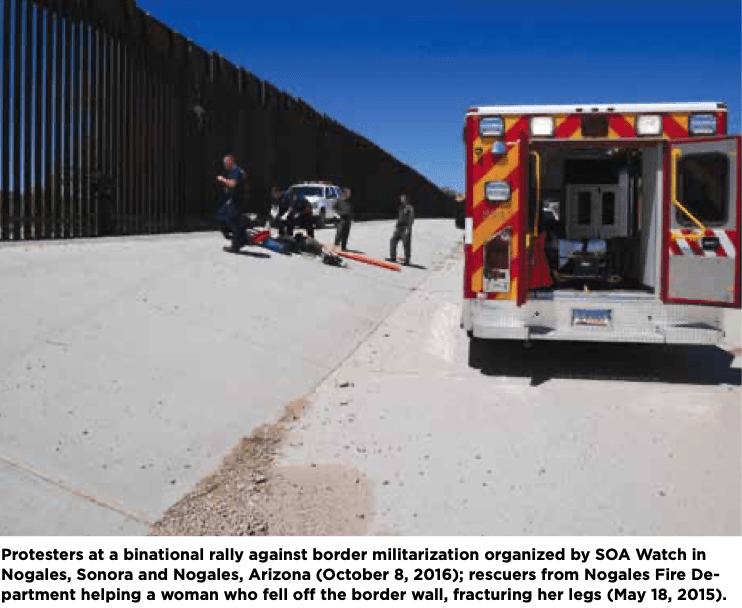

A young woman is two months pregnant. Three days ago she tried to climb the border fence separating Nogales, Sonora, from Nogales, Arizona, when she fell down. “It was just a meter and a half,” she explains why she did not go to the hospital. But yesterday she started having a pain in her lower back. We encourage her to see a doctor. She asks for medication. We double-check the instructions: ibuprofen, which is all we have, is not recommended during the last trimester of pregnancy; consultation with a health professional is advised for use earlier in the pregnancy. But she doesn’t want to hear about going to the hospital or seeing a doctor. “Take one or two every six hours. Don’t take more than six in twenty-four hours,” I explain, as Sarah pours a handful of red tablets into a small plastic box. I read and translate the warnings on the label, and she nods.

A young man just deported from the United States has a sore throat. But we are distracted by the bones in his forearm—they are dislocated and sticking out at the wrist. He tells us he broke his arm when he fell off the fence. He is from Monterrey but chose to cross in Arizona and not in Texas, because of the cartels. The Border Patrol found him and he was flown by helicopter to Tucson, he says. He shows us a piece of paper with a prescription for ibuprofen from one of the hospitals up there. His family lives in Washington, D.C.

Another man complains of toothache. He lived in Phoenix for nearly thirty years until one day he was caught driving without a license, spent three months in detention, and was deported. “I have nothing in this country,” he says about Mexico. His wife and children live in Arizona. He is waiting for a friend who expects to be deported to Nogales in the next few days. They will cross back together. He can’t go through the desert, he explains, because of hypertension. But his buddy knows the way through Ciudad Juárez. I give him ibuprofen. “This will numb your teeth,” Sarah says as she hands him a tube of Orajel.

A young Salvadoran is feeling dizzy. I invite him to sit down, wrap the cuff around his left arm and measure his blood pressure. He was in a hospital twenty days ago, where he received IV fluids. He shows us a prescription with the Red Cross logo which contains a list of medications for an intestinal infection. He says he had been walking for weeks and had nothing to eat for at least two days. We have no glucometer to check for hypoglycemia. We worry about electrolyte imbalances and anemia. One of the volunteers agrees to take him to the hospital. While he waits for the ride, he sips an electrolyte solution.

Security build-up on the border began in 1994, when the U.S. Border Patrol adopted a policing strategy they called “prevention through deterrence.” In towns adjacent to the international boundary, such as Nogales, El Paso and Tijuana, the height of the fence and the number of agents dramatically increased. The government also deployed state-of-the-art technology to detect trespassing: from ground sensors to stadium-style lighting to integrated surveillance towers and drones. Despite continuing protests in local communities, all roads leading away from the border have permanent checkpoints, where federal agents inspect vehicles for “illegal aliens” and illicit drugs. Instead of stopping unauthorized migration this strategy created a funnel effect, as migrants began crossing far from hyper-policed urban areas. In the desert, where the reach of the law (and cell phone signals) is weak or absent, they have been subject to assaults and extortion by criminals and left at the mercy of deadly temperatures. Those who make it across—after three, four, five days of walking in the desert—can be so severely dehydrated that their kidneys and other organs shut off.

No wonder that such security measures made travelling back and forth too risky. Undocumented seasonal workers, who used to come to the United States to find temporary employment in agriculture, construction industry or domestic services and then return home, were trapped. Afraid that they would not be able to cross again, they stayed and saved money to pay the coyotes to bring their spouses and children across the border. Compared to previous decades, many migrants traveling through Mexico on their way to the United States today are women and children. Some of them are off to el norte to join their husbands and fathers, who had already found a niche in the undocumented workforce. But not everyone has time to prepare for the perilous journey. Those in a hurry, most of them young, are fleeing gangs that have instilled fear and unleashed violence destroying their communities. The hondureños, their urban styles setting them apart from the rural folks in the comedor, are on the run for their lives. A small group of them is getting ready to cross later today.

Two men approach Sarah and me as we are sorting the medical supplies before we leave:

“Can you give us some pill that would help us walk?” one asks.

“There is no magic pill,” I tell them. I explain that they have to drink water, that headaches are caused by dehydration and that drinking enough water will prevent them. I also instruct the men to drink clean water because the water from the cattle tanks will make them sick. They listen, even though we all know that it is impossible to carry out my advice. To survive in the Sonoran Desert an average person needs to drink more than a gallon of water a day—that’s more than migrants can carry for a trip that takes at least three times longer.

I give them several tablets of ibuprofen for minor aches and pains. As I glance at the nearly empty bottle in my hand, I am relieved that no more patients are waiting to see us.

By now most of the migrants have left. Many are on their way to the offices of the local Grupo Beta, a government service dedicated to assisting migrants in Mexico; there, they can take a shower and get help finding shelter. We will probably not see them again when we return to the comedor next week—others will take their seats at the long tables, eat a warm meal, call their relatives, swallow some pills to cope with pain and be on their way out. Recycling displaced lives.

Winter 2017, Volume XVI, Number 2

Ieva Jusionyte is Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Social Studies at Harvard University. She is working on a book titled Threshold: Emergency and Rescue on the U.S.-Mexico Border. Field research for her project was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Wenner-Gren Foundation.

Related Articles

Displacements: Editor’s Letter

The sweet pure tones of a violin emanated through my grade school auditorium. Ten-year- old Florika, a refugee after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, was turning the warmth of once- living wood into a powerful source of communication. Florika spoke no English…

36 Hours (and More) in Cartagena

I arrived in Colombia in August 2014 on a Fulbright grant to research La Liga de Mujeres Desplazadas (The League of Displaced Women), an organization formed in the late 90s in…

Voices from the Atrato River

A traditional panga boat with thirty passengers cruises the mighty waters of the Atrato River in the Pacific region of Colombia, doing a 142-mile route from Quibdó to…