Patchwork Memories

Arpilleras and Reflections on Disappearance

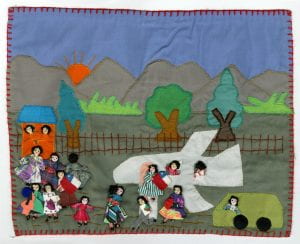

This detailed arpillera entitled Exilio 1974-1984-exile-depicts a sad airport scene as families and individuals were forced to flee Chile because of political persecution. Pidee Linares, Chile. Fondo Pidee. Courtesy of The Mudeo De La Memoria Y Los Derechos Humanos, Chile.

In every season of the year, Violeta Morales would dress exactly the same: a jacket, black skirt and a pair of worn-down shoes. A leader of an artisans’ group engaged in making intricate patchwork memory tapestries, Morales talked and created when others dared not.

Practically the moment I arrived back in Chile, she became my safe haven, my refuge, my anchor in a country in which no one was talking about anything relevant to human rights. Where silence reigned together with fear. Every single day.

I’d ask her over and over again, “Violeta, aren’t you hot? I always see you wearing the same clothes.” She would look at me with her olive-colored, always sparkling eyes, answering, “No, Marjorie, both I and my clothes have been frozen in time. Even my worn-down shoes accompany me on this perpetual journey.”

She taught me what it means to disappear, be forcefully disappeared, desaparecer. This extremely complex concept is almost impossibly untranslatable, causing us to reflect on this sinister condition invented by the military dictatorships of Latin America. To disappear is to be neither dead nor alive. It is to enter into a state of shadows. An act of violence, altered destinies, loss of lives, loss of illusions: a borderline state. And we seem to feel that the disappeared are evaporating bodies, ghosts that can only return to us through memory. To disappear is to be part of the history of absence. To search for the disappeared is to recover them so they do not dissolve into the forgetting that the repressive forces so cruelly intended.

Since 1973, I’ve worked very closely with the original group of women who make these arpilleras. This memorial patchwork honors the life of the relatives of friends who have disappeared. Working with all sorts of delicate materials often donated by charity organizations, the women cut out pieces of cloth and then these artists of memory recreate life through cloth, evoking the life of the home and hearth, the empty seat at the table, the first steps ever taken, the first day of school….

The arpilleras are true compositions and works of memory. The process of making them is a healing process, as well as a memorializing one. From the scraps of fabric that are sewn together emerge disappeared lives that materialize once again.

For these brave women, to disappear is to not cease to exist; it is not only to search for a body, but to reclaim the memory of a daily life. The arpilleras are sent to many parts of the world. They form part of a collective memory of a lost generation with its many who disappeared; other people will hang the patchwork tributes on the walls of their homes. The women will manage to always live with their pain and the memories—and to reconstruct those memories.

The patchwork art is similar to memorializing texts about the disappeared. Both have the ability to dredge up memories, to awaken the conscience, to make the absent present and in this fashion attempt to make the awful horror that disappearance implies transformed into the possibility of remembering what it means to exist. Fully human and not truncated lives, frozen at such an early age.

I frequently remember my encounters with the arpillera makers and our conversations about their disappeared relatives. These disappeared ones had names and fruitful lives. Irma Muller, mother of a disappeared son, observed that the tactile experience of the arpilleras reminded her of a soft caress. The arpillera maker who shows us a large window and a woman who looks out over the horizon, Violeta Morales would say to me, represents hope and the possibility of return.

With the arrival of democracy in the Southern Cone, the names of the disappeared indeed appeared on lists and in reports such as the well-known Rettig Report, officially the National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation Report, but even before then, relatives and community groups in support of human rights were remembering these names constantly; memory transformed into a demand to know the truth.

The crime of disappearance, considered a crime against humanity, affects entire societies and more than anything destroys the family fabric in a slash. Newborns never knew their parents. And they, those who disappeared, never watched their children grow up or their parents get old.

To remember them and to keep them from just becoming names relegated to official lists compiled by the human rights community, the arpillera makers, with nimble hands, create wall hangings with images embodied with gestures of solidarity, fruit-filled trees, rivers flowing with deep waters. They honor the memory of them, the disappeared, with images of life.

After the wars and the catastrophes that followed, the dead, the wounded and the disappeared in combat appeared on list after list. Relatives flocked to human services offices to ask about their loved ones and they congregated in those places united in grief and in a common history. However, the victims of forced disappearances in Latin America and particularly in the area I know the best, the Southern Cone, do not appear on any lists. Exactly the opposite. Military authorities deny their very existence. Many mothers of the disappeared from the harsh years of the 70s and 80s told me that they were told at military headquarters that their children had gone over the mountains and abandoned them. Sometimes, as Irma Muller recounted about her son Jorge who disappeared off a Santiago street in 1974, the military would charge, “Your son went to Cuba. He is a terrorist.”

Argentine writer Julio Cortázar once said that to disappear in Latin America was a “diabolical invention” of its own countries’ citizens. The disappeared simply do not appear anywhere except in the memory of those who so stubbornly look for them.

The frozen memory, the memory suspended forever and ever, the exhausting search, are all part of the daily experience of those whose loved ones disappeared. At first, the search is solitary, but later acquires a collective force when groups of desperate women encounter each other in places like jails and morgues to inquire for their family members.

In simple words—clear yet profound: Where are they? These three words convey the power of language to clamor for the lives of thousands of people whose existence was truncated, suspended. The moment that they disappeared was the moment they began to be looked for, and that search has not ended.

So many times, I’ve asked myself what kind of language to use in talking about the disappeared so they do not turn into mere legal statistics or a mere name on a list, at the petition of family members.

To talk about the disappeared, it is necessary to dwell in memory. To live and to feel, to imagine the disappeared in the spaces of the present, not in the void. In the coffee house, the concert halls, in schools, in the spaces of daily life, every day, every moment, and to maintain the memory of those disappeared as vibrant and fully there. And to try above all to create communities in which they are remembered, such as the movements that emerged in that period and continue on: the Mothers of the Plaza del Mayo and Active Memory (Memoria Activa), both in Argentina, and Women for Life (Mujeres Por la Vida) in Chile.

These movements are essentially activities in which the memory of the disappeared does not conflict with the official memories of history (some spell this “history” with a capital “H”), but works in a dialogue with that history; in the process of reconstructing through memory, witnesses and art in its various forms, ranging from music to the Chilean arpilleras—patchwork testimonies.

The memory of those lives transforms into presence, writing that recalls them is an act of conscience, and the mothers who embroider their stories and their names with fragments of cloth convert them into luminous memories that journey from one place to another.

We, the witnesses of these fabrics and these memorializing gestures, also contribute with our gaze in solidarity by not forgetting, in denouncing this sinister and diabolical crime.

I learned from these arpillera makers that with the love and the delicacy of the handiwork with which they craft these histories of them, the disappeared, and of us, that in this fashion perhaps they can negate the terrible plan of the Southern Cone dictatorships and others who wished to wipe out an entire generation, a generation for the most part of dreamers and of believers in solidarity. They did not achieve their evil goal.

An arpillera accompanies me above my desk. I feel its presence always nearby. Every day I look at it and I sense that the disappeared are not ghosts hidden in the shadows, but they are there, accompanying us in all our actions and in our active memory, seeking justice and light.

Related Articles

El Salvador Could Be Like That: A Memoir of War, Politics, and Journalism from the Front Row of the Last Bloody Conflict of the U.S.-Soviet Cold War

“There are no just wars. There are only just causes.” I was sitting in the modest home of a former FMLN guerrilla woman in a rural village in the northeastern corner of El Salvador. It was 2001, and I was nearing the end of my second year-long stint in this small Central American nation, interviewing more than 200 Salvadorans, mostly from rural areas, about their experiences during the civil conflict of the 1980s. …

First Take: Memories and Their Consequences

I visited the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos in Santiago, Chile, two years ago. It was a heart-rending experience. To enter the museum, I moved through a stark and subterranean passage and found myself in a somber space of transition. There, a wall of photographs transported me back in time—long ago in a messy graduate student lounge in Cambridge, Massachusetts, four of us stood in shock …

An Exploration of the Mexican Health Care System

The recent creation of Seguro Popular—a governmental program granting basic health services to millions of Mexicans previously uninsured—has newly enabled thousands of Mexican women afflicted with breast cancer to access treatment. With the growing prevalence of breast cancer survivors, the question now arises of how best to maintain their health and address their needs. …