Pleasure is Power

Invading, Conquering and Dominating through Celebration

They approached, singing:

“Yo vivo en el agua, (I live in the water,)

como el camarón, (like a shrimp.)

Y a nadie le importa (And no one cares OR It’s nobody’s business)

como vivo yo” (how I’m living.)”

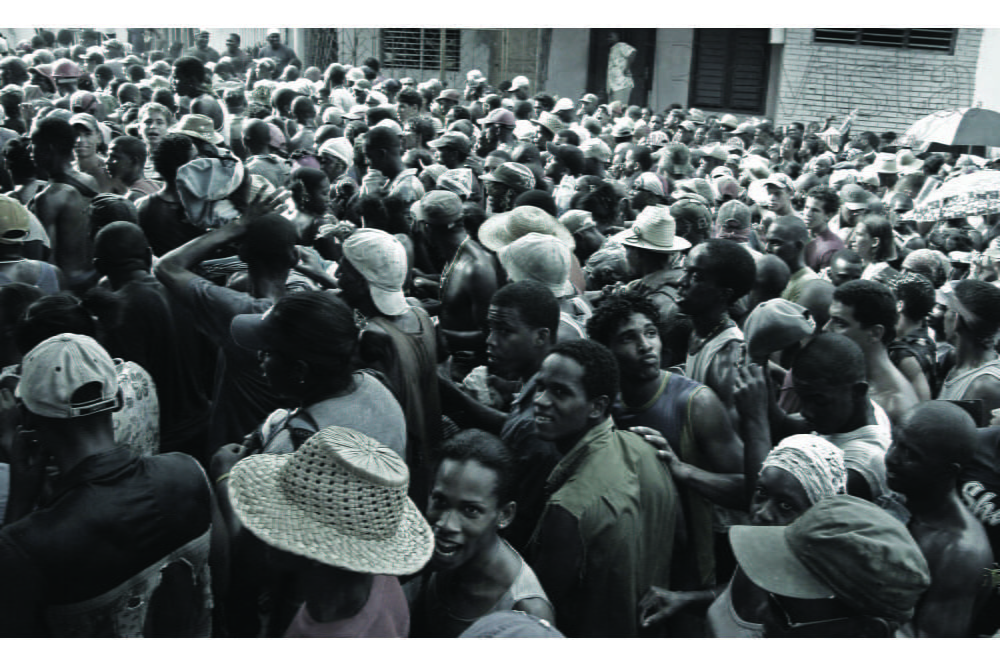

I was a little late to the parade called La Invasión (the invasion)—the largest street parade in the conga tradition of Santiago, Cuba. Then I heard this simple song and was overcome by pleasure in it and in the thrill of witnessing two unlikely lovers—partying and authority—on a date. It was just past noon on December 28, 2002. It was hot—really hot!—but the thousands of people along Martí Avenue were ready and willing to rebel against not only the heat, but also against anything with any semblance, real or symbolic, of power; “it’s nobody’s business how I’m living,” they sang, watching and dancing. The joyous individuals that day were free, having conquered the here and now. The procession, amid shouts of enjoyment, somewhere between pleasure and violence, was the climax of a community; its very name suggests it: this conga is “por la Victoria” or “for Victory.”

The idea for this parade came from the First Secretary of the Communist Party in the province of Santiago, Juan Carlos Robinson, in 1996. He wanted to commemorate the anniversary of the Cuban Revolution (the actual date was January 1) with an Invasión of the conga each December. It also, however, served to alleviate some of the effects of the crisis that hung thick over the city at the time, the special period of austerity that battered Cuba after the collapse of the Soviet Union. This new celebration, for those who live “in the water like a shrimp,” has turned into an offshoot from the traditional and well-known Invasión parade that is a prelude to Carnival.

Traditionally, La Invasión takes place a few days before the beginning of carnival every July, which honors Santiago the Apostle, the city’s patron saint. La Invasión lasts about five hours, leaving from the largely Afro-Cuban Los Hoyos neighborhood, and winds through a large portion of the city, “invading,” quite literally diverse ethnic and class zones of many differing ethnic and class makeups. Throughout the route it typically encounters other congas from different parts of the city.

This forms a constantly shifting reality, especially because of a type of inverse gentrification in which poor people flooded into the cities after the Revolution. It becomes a literal invasion by the others as they enter the Sueño (Dream) neighborhood, which is a mostly white, middle-class area, in stark contrast with Los Hoyos (the Holes), a mostly black and mixed-race neighborhood, where the parade begins.

We climb the hill on Martí Avenue. A young woman rubs her buttocks against a policeman’s fly, moving it to the rhythm of the music, with her head and torso inclined forward. The movement is sexual without a doubt! He attempts, quite poorly, to repress a smile. Gently, he taps his riot stick, tool of repression, on her rear. Are these taps his way of symbolically caressing this girl’s body? She shouldn’t be right up against him. The policeman seems to debate between fulfilling his duty to bring order and ignoring it to enjoy himself. The young woman has succeeded in dominating him—at least for the moment—but then people begin to push, a fight breaks out, the police begin to strike the crowd, and the power shifts. The game has changed… but she’ll be back!

Women in the conga parades often play the role of easing tensions and maintaining a relatively safe space. They sensually dissuade the police from acting aggressively toward the crowd, taking advantage of the benefits of being close to the structural dominator. While the police form a circle around the musicians of the conga, shielding them from the crowd, the women in turn surround the police, offering them both closer enjoyment of the music and better protection from crowd violence, which is fundamentally masculine. But since this parade is, above all, a way to expose oneself, to play with our masks, everyone is a potential victim or victimizer, and end up being both, de facto. The police don’t act against women with as much force as they do against men, so this arrangement creates a slightly more peaceful zone; it isolates the police, giving the crowd a temporary shield, easing the pressure. The ladies conquer, and as a consequence, so does the crowd.

The invasion continues to move—and I move along with it. In Sueño, the Conga passes the old Moncada Barracks, an icon of the revolution, now ignored as the energy of the celebration rises to the next level. The rum and collective fervor accompany the growing intensity of the music. The corneta china, an Asian instrument brought to the island by Chinese immigrants, urges on new songs. In front of the barracks a fight breaks out, the police intervene with blows in all directions, people run, total chaos. Suddenly a song begins—“cógele la nalga al guardia” (grab the policeman’s butt)—everyone repeats it, each time louder and in unison, euphoria, the police are helpless, always helpless against the songs, which are public domain. Nothing is sacred; the laws of freedom inherent to celebrations take over and in practice police action against transgressions is simply not viable.

The police protecting the musicians begin to make a space for them in a narrow stretch of the street. I see a policeman hit a young man. The young man looks at him and with a very theatrical gesture says “conmigo no, con los americanos” (forget me, go after the Americans) and a group near him begins to sing:

“Conmigo noooo (Forget meeeee)

Con los americanos (Go after the Americans)

Con los americanos (Go after the Americans)

Con los americanos (Go after the Americans”)

Don’t attack me, do that to the Americans, to those in power. As the singer Rubestier, who created this chant some ten years ago, put it, “I made a chorus saying (to the police): why are you gonna mess with me, if we’re just partying? Go over to America, where the real problem is!” These songs reflect events that affect the community: they are an acted chronicle. Rubestier also gives us an idea of how these parallel discourses arise in public places of celebration, where the people say—or rather sing—things which are far from the official discourse: “…it is different from a theatre…in the conga, on the streets, feelings are expressed more… it is like a release of tension… the police look the other way because once the conga is over, it’s over. It was just the conga, and now it’s done!”

Of course, feelings are expressed differently on the streets in any carnival, but in the Cuban case, taking into consideration the well-known government control over public opinion, it is very interesting that the community is given this open door for self-expression during these public celebrations.

In each neighborhood the amount of people, and the amount of alcohol, increases. There’s no conga without percussion, but without rum? Forget it! People begin to drop leaves in the street. The leaves of various plants are used to clean the body and spirit of negative energy—a common practice in the Afro-Cuban religious tradition, especially Santería. The leaves of different plants are used, and each plant has its own specific meaning. Once the revelers have used them to strip themselves of negativity, they throw them to the ground, to the past. Shoes also begin to appear in the wake of the parade: shoes that have fallen off, or broken, mostly sandals, of poor quality or simply no longer wanted. Some people just go the whole way barefoot.

People appear in doorways and windows; some dance and sing; others watch and judge, but from a distance. Some stay out of it because of racial or class prejudices; others simply shy away from the excesses. They are just spectators; the actorshere have an audience, and these singers, dancers and musicians aim their play towards these spectators. They are conscious of being observed, and need to release what they produce to an audience.

Not everyone is enchanted by congas and carnivals. For comments against the conga, look up what rum magnate Emilio Bacardí said about carnival, even though his company benefited from the tradition greatly, or the statements of the former mayor of Santiago, Desiderio Arnaz. In an ironic twist of fate, his son, Desi, who starred in the popular U.S. television program I Love Lucy, actually helped popularize the stylized version of the conga, which has since become universal. (See N. Pérez Rodríguez, El Carnaval Santiaguero [Santiago de Cuba: Editorial Oriente, 1987] and R. D. Moore, Música y mestizaje. Revolución artística y cambio social en La Habana. 1920-1940. [Madrid: Editorial Colibrí, 1997]).

But my mind right now is not on the theoretical aspects of carnival. Crossing Madre Vieja Street, we arrive at Aguilera. Santiago is dilapidated but nonetheless beautiful. The city is mountainous and plunges downward towards its bay, so from the top of the hill on Aguilera you can see the summit of another hill, sometimes more than one; now what we see are hills covered with people. It is a magnificent spectacle.

We are now close to the intersection of San Miguel Street. This is my neighborhood. I can remember the excitement during my childhood when the Invasión approached and we children impatiently awaited its arrival, the pungent aroma of heat and bodies, a subterranean rumble that alerted us that they were near, the invading hordes were coming to occupy. I remember my mother and her warnings not to leave her side—it was dangerous, people took little children and ate them—but the temptation was stronger than her words. Although we were all black and mulato, in my family I had the lightest skin. My cousin warned me—they’re gonna f*** you up in there, blanquito (whitey), so don’t you come with me—but I went. Either I would escape or my neighbor Maida would rescue me. She loved the conga. A white woman whose father was a former official in the government of the dictator overthrown by Castro, she lived in a beautiful spacious house next to ours, which was the exact opposite. And her daughter was my secret girlfriend. Maida, my angel!

The Invasión pauses for a bit. In some areas people begin to argue, in others people dance and sing in small groups, they create a beat with glass bottles, drums, claves, any object that can produce sound. Some just clap their hands. It’s time to enjoy a live concert. I hear a group singing:

“Yo no quiero Panda (I don’t want a Panda TV)

Ni quiero teléfono (I don’t want a phone)

Yo no quiero na’ (I don’t want nothin’)”

Another guy improvises:

“Lo que quiero es un celular (What I want is a cell phone)

Pa’ llamar al yuma (To call the US)

Coro: rinng, rinng, pa’ llamar al yuma(Chorus: ring, ring, to call the US)”

To put this in context: the Cuban government authorizes the distribution of Chinese “Panda” brand televisions and telephones. As there were not enough for the entire population, they were given out to a selection of the “best neighbors” in every neighborhood. This practice resulted in frustrations and problems in the communities and in this popular carnival chant.

Laughter. Laughter and celebrating are our tools of vengeance: sarcasm, irony, dark humor, or as it’s called in Cuba,choteo—but way beyond what J. Mañach described in 1955 in Indagación al Choteo (La Habana: Editorial Letras Cubanas, 2nd ed.).These are not temporary rituals, as theorized by Victor W. Turner in “Pasos, márgenes y pobreza: símbolos religiosos de la communitas,” in P. B. Glazer and P. Bohannan (eds.), Antropología, Lecturas (La Habana: Editorial Félix Varela, 2nd ed., 2003).

We play, use, allow ourselves to be used by, negotiate and taunt authority on a day-to-day basis. Cubans know this, our spirits slip through the epistemological framework of the other; this is our best weapon in this bitter fight for survival.

It’s true that our carnival is not a “pristine” example of resistance: the means of control, use and domination by the state over the celebrations are undeniable—in Cuba today they are easy to see. But we can affirm, without a doubt, that Santiago’s conga parade is an example, albeit not pristine, but nonetheless powerful, of social resistance. I would say that these street parties are a specific type of struggle against the forces of domination.

We are on Trocha Avenue, where a trio of young gay men can be seen dancing with female friends. They are not trying to look like transvestites, but they are decked out—cross-dressing is a tradition with a long history in the congas and carnivals. Though this tradition is being lost, you can still see men with feminine masks, wigs and clothing. It is also true that in the last, say, 20 years the presence of openly gay men has increased in these parades, showing a tendency towards newtransgressions. Historically, this play had been reserved for “real men,” men who may simply have fun by dressing up like women.

A group of singers accompanied by a single conga drum grabs my attention:

“Maní maní (Peanuts, peanuts)

que yo no vendo avellana (But I’m not selling hazelnuts)

que yo no vendo avellana (But I’m not selling hazelnuts)

yo vendo mariguana” (I’m selling marijuana)

The group responded at the top of their lungs, unabashedly repeating what this singer put forward. For now, let’s leave this singer unnamed, because to say something like this in public, in the middle of the street in Santiago de Cuba, is far from advisable. Marijuana is not only taboo: in our community it is harshly penalized by law. Just a month after this parade the Cuban Ministry of the Interior carried out a police operation called “Coraza” and an unknown but very visible amount of drug traffickers were sent to prison on long sentences.

This same group starts another interesting song:

“Para el nuevo año yo quiero mi lancha (For the new year I want a boat)

yo quiero mi lancha (I want a boat)

yo quiero mi lancha (I want a boat)

que éstas no me alcanzan” (Cause these aren’t enough for me here.)”

In Santiago de Cuba? To mention boats on the island, as ironic as it may sound considering it is an island, is like calling for the devil, especially since the 1994 balseros crisis, in which thousands of rafters took to the sea when the Cuban government authorized the departure of anyone who wished to leave for the United States. Boats are symbolic of fleeing, betrayal, breaking the law. As a matter of fact, a few months later, in April 2003 the Cuban government would execute three young men, after a quick investigation and trial, for attempting to hijack a passenger ferry in Havana; but right now this group of young people not only asks for boats, they laugh about it!

In contrast, as we approach the San Agustín Pizzeria, others sing:

“que le pasa a Bu’ (Bush) con mi Comandante (What’s Bush’s problem with my Commander [Fidel Castro])

que le pasa a Bu’ (What’s Bush’s problem)

con mi Comandante?” (With my Commander?)”

That’s just how it is! Right in front of the Pizzeria we face the Conga de San Agustín, which represents the neighborhood we are in. In every neighborhood the congas greet each other by playing, or they challenge each other, sizing up the competition, because they are rivals and compete for a prize during the carnival.

We are now descending the hill on Trocha, while more people join in; the march has gone on now for about three hours. A policeman gets temporarily isolated in a dispute. A few men come at him, he defends himself as best he can but they surround him—bad sign—but more police soon come to his aid and the balance of power shifts. They arrest one man. They hit him. The crowd, in a frenzy, starts a chant aimed at the police. It is direct:

“abusador (abuser)

abusador (abuser)

abusador (abuser)”

I decide to enter once more the police circle that protects the musicians, now that things are getting crazy on the outside. I am a friend of the band, I’m wearing the t-shirt that identifies them and the police allow me to pass. I am one of the privileged ones. The musicians manage to have their friends there with them, along with certain tourists, friends from abroad and girlfriends; it is their moment of negotiation of power. I can hear the music well now, drums, bells, and cornetacreate a unique and magical polyrhythm. From here I can also be, for a moment, both spectator and spectacle, I can see more or less what is happening on the outside and those on the outside can see me well, it’s the eye of the storm.

It is getting dark by the time we get to La Alameda Street, which is right on the bay, and from a certain point you can see the ocean. This is enough to inspire a song:

“tamo en la Alameda (Short for “estamos”. The letter “s” is often left out of speech in Santiago, and the word fits into the song better this way.) (We are on Alameda)

¿dónde está mi lancha? (Where is my boat?)

¿dónde está mi lancha? (Where is my boat?)

¿dónde está mi lancha? (Where is my boat?)”

There is fun all around, there are fights, explicit demonstrations of sexuality, but the party is nearing its end. It’s already night when we return to Martí Avenue, to the home of the Los Hoyos conga. I am tired but happy. My friends and I share a few final sips of bad rum, which at that moment helps me to remember the poet Virgilio Piñera.

“..Y gritaré con ese amor que puede (And I will scream with this powerful love)

gritar su nombre hacia los cuatro vientos, (scream its name at the top of my lungs)

lo que el pueblo dice en cada instante: (what people say at every moment)

“me están matando pero estoy gozando”. (“they’re killing me, but I’m having a ball.)”

Spring 2014, Volume XIII, Number 3

Tomás Montoya González is a native of Cuba and resident in New Orleans, Louisiana. He is currently finishing his doctoral degree at Universidad de Oriente in Santiago de Cuba, and working on a documentary examining the role of popular celebrations and the power relationship in Santiago’s community. He is a photographer (finalist of NOPA’s Michael P. Smith Fund for Documentary Photography 2012 Grant), poet and arts organizer (He has organized several trips for CubaNola Collective to examine culture in Cuba). He teaches at Tulane University in the Spanish and Portuguese Dept., 2007-2014.

Related Articles

Festival and Massacre

Festivals are privileged spaces to help us understand the meaning of community. They are a special way of presenting historical narratives, bringing…

Fiesta and Identity

English + Español

In Barranquilla the days of Carnival begin early. From the first hours of the day—already confused with the last hours of the night—the smells of celebration are in the air. The streets…

Fiestas: Editor’s Letter

At the Oruro Carnival, a few hours from La Paz, the heavy-set blue-skirted women swirl past me in a dizzying burst of color and enviable grace. The trumpeters, some with exotically dyed hair, blare not too far behind. I remember that as a young man President Evo Morales had been a trumpeter in this very carnival.