Port City-Scapes

“Malecón, Havana” by neiljs is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Ports, for a kid raised hundred of miles away from the sea, were just holiday spots where we could see fishing boats come in with their catch. On special days, my family would buy fresh fish from the boats for our dinner. Docks, quays and piers were but the promenades of sojourners eager to rest after busy mornings at the beach and the site of dramatic sunsets. There also were other ports, just as smelly and equally as puzzling to me. Huge cranes rested beside enormous ships whose functions were as mysterious to me as the flags on their masts. These ports were surprisingly placed in the very center of cities without nice sea views. They were surrounded by derelict buildings and neighborhoods that later on I would learn were actually quite picturesque.

At home, once again far from the sea, ports appeared to me in adventure books. Smugglers, pirates, and old sailors with stories aplenty resided in alluring taverns that I had never managed to find in my teenage wandering days. Bars, lodging houses, cheap hotels and old shops did not attain the charm that was described in Pio Baroja’s novels. Indeed, the fish ports retained romantic traits that the port cities did not have. The port cities that I visited were generally industrial and the workers hardly resembled Stevenson’s characters.

A few years ago, I was again intrigued by the thought of ports and their cities. Port cities were, according to others, non-fiction literature, spaces of cosmopolitanism, a crucible of ingenuity and a melting pot of diverse ethnic groups. Yet, as an anthropologist who dealt with society and cultures from a temporal perspective, I was struck by quite a different perception: ports could be dynamic human artifacts promoting people’s interaction and ingenuity, spaces of hope and human growth, though they could simultaneously be areas of segregation and exploitation, human nests of deprivation and moral decay.

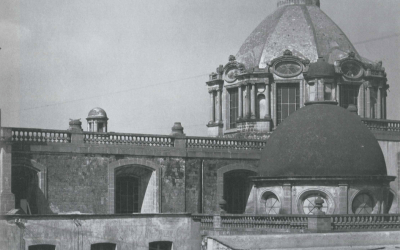

Ports not only shared other cities’ qualities of a social and culturally constructed urban milieu. In many cases, they were gateways to the future. In the Americas, ports were the first beach heads of colonization and where many immigrants landed, hoping for a better future. By studying the remains of port cities we can ascertain much about the lives of those people who did not make it into history books but whose stories knitted greater narratives. Ellis Island in New York, the impressive fortresses of Havana, and the Buenos Aires waterfront in the Boca neighborhood all tell us important stories.

The various aspects of ports are good to ponder for they reflect many qualities of citizenship. Their past evolution gives us a glimpse of how the most stubbornly human built structures, the ones that tended to require more planning and cunning, provide social scientists and historians great case studies to analyze.

Nowadays, Latin American ports are following the wave of port and waterfront renewal that many other decayed port marinas have experienced during the last three decades in the United States, Canada, Western Europe and South Africa. These renewals are great reflections of new ideas about how the interface of city and the old port should be: environmentally friendly and more consumer-oriented than public venues of non-structured citizen activity. The new waterfronts house aquariums, malls, exhibition halls, movie theaters and, though keeping past roots intact, are a radical departure from the way ports were. Latin American port and city authorities as well as citizens and entrepreneurs have the chance, as do many other port cities interested in their urban renewal, of showing alternative modernities and visions of postindustrial progress.

Related Articles

Bogotá: A City (Almost) Transformed

The sleek red bus zooms out of the station in northern Bogota, a futuristic symbol of an (almost) transformed city. Nearby, thousands of cyclists of all ages enjoy a sunny morning on Latin America’s largest bike-path network.

Editor’s Letter: Cityscapes

I have to confess. I fell passionately, madly, in love at first sight. I was standing on the edge of Bogotá’s National Park, breathing in the rain-washed air laden with the heavy fragrance of eucalyptus trees. I looked up towards the mountains over the red-tiled roofs. And then it happened.

Social Spaces in San Juan

My city, San Juan, is a social city. Its character and virtue are best illustrated and defined by the collective and individual memories of its people and those places where we go to spend time in idleness….