Prospects of Peace

Sharing Historical Memory in Colombia

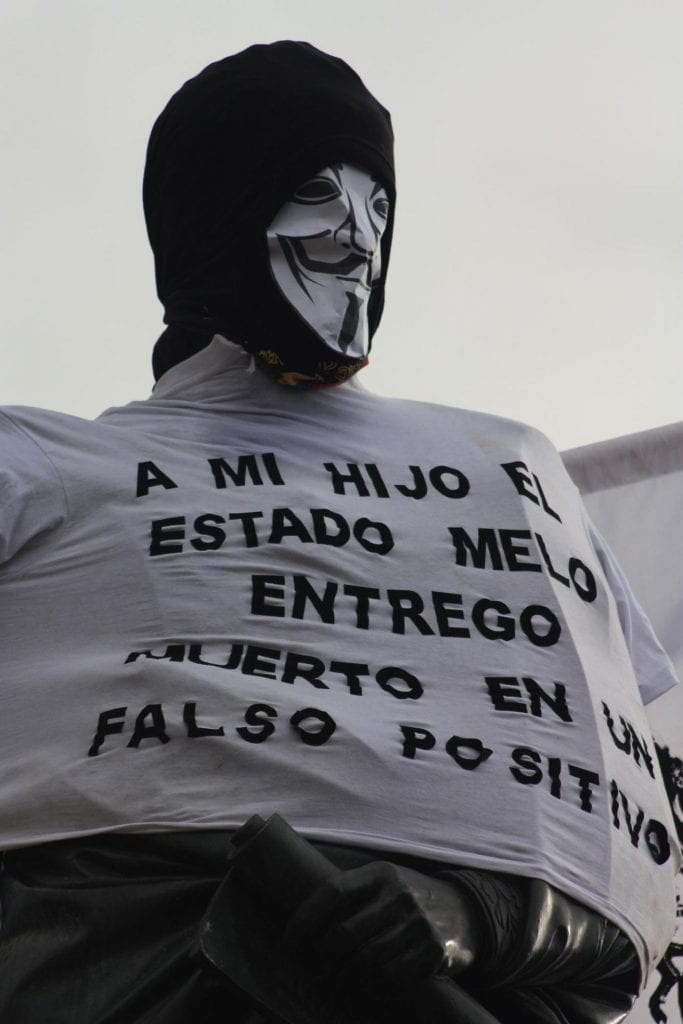

Sign in the April 23, 2012, march, “dress rehearsal” for the April 2, 2013, Marcha Patriótica, reads, “The state returned the body of my dead son, a false positive.” Photo by Fabio Lopez De La Roche

On April 9, 2013, tens of thousands of citizens filled the streets of Bogotá in a massive demonstration “for peace, democracy, and the defense of the public good.” Many of them had traveled from the farthest reaches of rural Colombia to march with poor, working, and middle class city-dwellers in support of the negotiations being held between the government and the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) guerrillas.

These demonstrators—fed up with the militarization of daily life—had been mobilized by a coalition of the government, labor unions and some leftist politicians. Among them could be found the invisible and marginalized face of the country: settlers from the agricultural frontiers, indigenous people defending their traditional form of property, representatives of black communities on the Pacific coast with their own collective property rights, and campesinos from every part of the country.

This event, a new vision of the country’s national memory, promises to be remembered as a turning point when relations among allies and foes entered uncharted territory, opening possibilities theretofore considered unimaginable.

The physical setting chosen for this dress rehearsal for national reconciliation was the Avenida El Dorado, sometimes referred to since the early years of this century as the Avenue of Memory, a reference point from which to recount the country’s past for those of the new millennium. Along the avenue, two memorials have arisen, each representing an opposing vision of the country’s history.

The first is the Monument to the Heroes Fallen in Combat, built by newly-elected President Álvaro Uribe in 2003 and located across the street from the Ministry of Defense. From its beginnings, the grounds of the monument have been used as a staging area for military parades and other commemorative events organized by the armed forces. Over the course of his eight years as president (2002-2010), Uribe insisted that the main problem in Colombia was that groups of criminals, outlaws, and terrorists held the great majority of good people hostage, hindering the country’s social progress and economic development, and that only the courage and dedication of the armed forces could bring about the revival of the fatherland.

A publicity campaign was launched, proclaiming that “Yes, there are heroes in Colombia,” initially referring not only to the police and military, but also implicitly to Uribe, the strongman who would pacify the country at whatever cost by implementing the hardline anti-insurgent policy called “Democratic Security.” Paradoxically, those who supported this aggressive approach also denied the existence of the armed conflict, since to have acknowledged its reality would have required them to recognize that the insurgents had a role to play in the country. It was not surprising that the former president lashed out at the April 9 mobilization as a “march with the terrorists.”

The second memorial is the Center for Memory, Peace, and Reconciliation, built on the grounds of the city’s Central Cemetery, where many victims of political violence are buried. The Center is a monolith that resembles a large gravestone, penetrating into the earth and into the entrails of the city’s past—the very roots of the Colombian conflict, from which its victims may symbolically reemerge.

The Center was established on the initiative of civil society organizations with the support of the city government, to demand the right to memory as an exercise in active citizenship. The goal was to open in 2010, but in 2009 excavators working on the site unexpectedly uncovered the city’s historic Paupers’ Cemetery. The city government then had to decide whether to proceed with construction.

At the same time, it was discovered that between ten to thirty thousand people had been buried in thousands of mass graves around the country in recent years. They were the victims of selective killings, massacres, and extrajudicial executions carried out by paramilitaries, guerrillas and the armed forces.

Terror at the horrific discoveries coexisted with the all too common indifference, and in this climate it was decided that unearthing the largest mass grave in the capital city’s oldest cemetery could not be treated as a routine administrative problem. Construction of the Center was delayed while 3,000 sets of remains dating from 1827-1970 were carefully processed. It turned out to be Latin America’s largest archeological project involving modern urban history.

Thus, the site of the memorial was until recently but a large hole in the ground where engineers and laborers toiled alongside forensic anthropologists working to restore dignity to the anonymous dead of Bogotá, just as their colleagues were doing with the remains of victims of the conflict hastily buried in isolated rural fields all around the country.

A mass grave underlying the Center of Memory was an apt but terrible metaphor that only emphasized the urgent need to come to terms with the past and exorcize the demons of war. The Center finally opened its doors to the public in late 2012.

The institutional events of April 9 were meticulously choreographed to maximize their symbolic value. President Juan Manuel Santos began the day by delivering a highly patriotic speech to an audience of generals and other military and police personnel at the Monument to Fallen Heroes.

Then he walked up the Avenida El Dorado to the Center for Memory, Peace and Reconciliation with a group of top government officials to pay respects to the civilian victims. They were met there by Bogotá’s Mayor Gustavo Petro, Vice-President Angelino Garzón, a group of foreign diplomats and other top city officials.

The event brought together a president who had been minister of defense during some of the most violent years of the conflict, a vice president who was a former union leader and former vice president of the leftist Unión Patriótica, and a mayor who was a former member of the M-19 guerrilla movement. Together they planted a tree of peace in the cemetery where anonymous victims of the Bogotazo lay buried. This remarkable event received the backing of the international community, the blessings of the high command of the ELN (National Liberation Army guerrillas) and the approval of the FARC negotiating team in Havana.

The date chosen by the organizers marked the first-ever official commemoration of the April 9, 1948, assassination of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, a traumatic event which had led to a spontaneous insurrection called the Bogotazo and a civil war known as La Violencia, leaving gaping wounds that remain unhealed to this day.

Until a few months ago it seemed that the Colombian state had nothing to say with respect to the day that had fundamentally changed the country’s destiny. For decades there were no public commemorations or military parades, not even symbolic acts. A systematic policy of forgetting sought to erase any memory of these events from the public sphere.

Grass-roots organizations, however, tried to keep the collective memory alive. On the 60th anniversary of the Bogotazo in 2008, for example, they undertook a multiplicity of independent initiatives, including street theater, mural painting, musical performances and flash-mobs.

This situation took an unexpected turn when Juan Manuel Santos became president. In order to promote large-scale mining, agricultural exports, and infrastructural development, the new governing coalition led by Santos decided to seek a peace agreement with the FARC.

After all, the ravages of an ongoing war would preclude capitalist investment in the many rural areas battered over the previous 20 years by the forced displacement of more than four million people through death threats, selective killings and massacres; the illegal seizure of more than 12 million acres of land by drug traffickers and paramilitaries; political or for-profit kidnappings; the indiscriminate use of anti-personnel mines by the guerrillas, and a chaotic land titling regime. All these obstacles to development had been caused or exacerbated by the armed conflict.

Indeed, the new government’s 2011 Law on Victims and Land Restitution was passed as an important tool to bring about an overall reorganization of rural territory and determine the fate of the beleaguered rural population.

As minister of defense under Uribe, Santos had denied the existence of an armed conflict, despite glaring evidence to the contrary. As president he was forced to alter this position, given the need to implement transitional justice. Remarkably, Colombia transitioned from a non-conflict to a post-conflict scenario without ever coming to terms with the conflict itself. In addition to economic reparation, the need for visible acts of symbolic reparation led to the proclamation of April 9 as National Victims Day, to mention just one example.

The government was not alone in revisiting the traumas of the past with an eye to its current political interests. The opposition also hoped to gain political space by pointing to unresolved crimes committed against it. Some sectors of the left under the leadership of Liberal Party activist Piedad Córdoba came together in a new organization called the Marcha Patriótica (Patriotic March).

The new organization’s name clearly evokes the Unión Patriótica (Patriotic Union), the electoral party that emerged decades ago from a previous set of peace negotiations with the FARC and other guerrilla groups. The Unión Patriótica was virtually exterminated in the 1980s and 1990s when more than 3,000 party candidates and other members were systematically gunned down.

The message is clear: the reference to the Unión Patriótica calls public attention to the specter of a peace process that ended in an exterminationist campaign whose perpetrators enjoy impunity to this day. Peace with the guerrillas will be possible only if the state can provide guaranties that this macabre history will not be repeated.

On April 9, 2013, the Marcha Patriótica took its impressive political and electoral potential to Bogotá streets. Long-deceased victims of unpunished atrocities were vicariously endowed with legal standing and embodied by the demonstrators, raising their voices to demand an end to hostilities.

On the very day of its 65th anniversary, a tragic and forgotten but pivotal event became a reference point for the memory of its immolated victims in a conflict whose existence was officially denied just a few months before. The phantasmagorical presence of a past unacknowledged in official versions of history now has a role in influencing the course of present-day struggles.

The most noteworthy aspect of the April 9 march was the unexpected convergence of antithetical ways of remembering the past, interpreting the present, and imagining the future. Two very different narratives underlie these visions of national life.

One describes a country full of happy, hardworking people who live at peace in a paradise of natural beauty and great natural wealth, defying the vile misdeeds of a handful of criminals. This is the vision promoted by populist neo-nationalists, best encapsulated in the advertising slogan and exercise in national branding Colombia es Pasión (Colombia is Passion).

An alternative narrative emphasizes the pervasive violence, insecurity and corruption that have marked the lives of generations of Colombians: an entirely different kind of passion that recalls Jesus’s suffering on the Vía Dolorosa before his inevitable resurrection.

These alternate visions reflect the two mechanisms used in Colombia today for the public use of history, presenting contending poetics and political orientations. One of these mechanisms makes use primarily of the country’s cultural patrimony and the other its historical memory.

Those who prioritize cultural patrimony seek to produce least common multipliers, focusing exclusively on fragments of the past that generate consensus based on what are assumed to be universal values. Any reference to class, race, or gender-based conflict is suppressed or relegated to a distant place and time.

In contrast, the mnemonic technique engaged by historical memory stresses the greatest common divisors of social life: unameliorated offenses, unresolved conflicts and dreams deferred. This approach emphasizes making conflicts visible but hinders an appreciation of life-affirming projects and the texture of daily life.

The mechanism of cultural patrimony tends to evoke the everlasting glory of the idealized nation and relegate the exotic other to the realm of folklore, while that of historical memory tends to memorialize victims and reify the past. Each operation highlights the rescue of certain legacies to be bequeathed to future generations, at the same time running the risk—if no form of dialogue and accommodation between the two is found—of undermining the potential for the active citizenship and cultural agency required to produce a collective, durable reinterpretation of the past.

By participating in the mass march on April 9 Santos hoped to conciliate antagonistic anniversaries, spaces and narratives and to conciliate these two uses of memory. Hopefully his gesture will help bring into being the much-yearned-for ceasefire with the FARC. If the government fails to come to terms with the many unresolved problems that contribute to the Colombian predicament, on the other hand, the president’s participation may turn out to have been nothing more than a short term maneuver to further his prospects for reelection.

The Colombian situation is one of a kind. First, unlike the Nazi Holocaust, the democratic transition in the Southern Cone or post-apartheid South Africa, the dispute over memory in Colombia is taking place in the middle of an armed conflict with no negotiated solution yet in sight. Any eventual FARC demobilization would not in itself be sufficient to bring about peace, since armed criminal gangs, drug traffickers and ELN guerrillas also operate at this time.

If policies to generate a culture of memory and to turn the page on decades of systemic violence are to bring about true national reconciliation, they must also confront the country’s generalized impunity and its social inequality, which are among the highest in the world and reflect deeply ingrained social oppressions based on race, class and sex.

A second factor that makes Colombia sui generis is that a process of transitional justice cannot be limited to a reparative act by the state to compensate for its own criminal acts, since the state is only one of the actors that have systematically violated human rights. What can be made of historical memory when a conflict is dominated by criminal organizations and illegal armed groups?

A third characteristic also makes Colombia a unique theoretical and practical laboratory for historical memory. For decades, the struggle against forgetting and impunity has been conducted from below by victims’ associations and other grass roots organizations, often at the cost of violent repression.

Only in the last three years have these movements been supported by public institutions, and this has frequently led to cooptation. The participatory practices necessary for decentralized grass roots decision-making must be institutionalized in order to make the distribution of powers more equitable.

A possible solution is to think of the past as a common good that cannot be reduced to an official public history proffered by the state, nor to a collection of private, fragmented, and unconnected personal stories.

Given the extraordinary social energy displayed in massive citizen mobilizations against forgetting, it is possible to imagine the construction of a collective memory that allows for the agency of subjects previously relegated to the margins of national life, in the process reducing the armed actors’ room for maneuver.

This would also require the state’s repressive apparatus to accede to the rule of law, allowing for the viability of a participatory government based on a shared past. In this sense the struggle for memory establishes the conditions for a negotiated peace and a consensual future. This is an enormous challenge, but the events of April 9 allow us to discern it taking shape on the horizon—as a possibility.

Paolo Vignolo, PhD in History and Civilization at the E.H.E.E.S of Paris, is Associate Professor at the Center of Social Studies of the National University of Colombia, Bogotá. He was a DRCLAS 2012-13 Julio M. Santo Domingo Visiting Scholar. Andy Klatt translated this article. <www.andy-klatt.net ><andy.klatt@gmail.com>.

Related Articles

A Search for Justice

In 2004, when I left Harvard and last saw you, I thought I would never learn the truth of what exactly happened to Carlos Horacio in the horrendous holocaust of the Palace of Justice in Bogotá. Yet fate was holding a tremendous surprise for my daughters and me, filled with…

Memory: Editor’s Letter

Editor's Letter Memory Irma Flaquer’s image as a 22-year-old Guatemalan reporter stares from the pages of a 1960 Time magazine, her eyes blackened by a government mob that didn’t like her feisty stance. She never gave up, fighting with her pen against the long...

A Search for Justice in El Salvador: One Legacy of Ignacio Martín-Baró

In the small rural town of Arcatao, Chalatenango, Rosa Rivera clung to the hope that one day she would find the remains of her disappeared mother and father and lay them to rest in peace. Others sought to exhume mass graves hoping to recover bodies of nearly 1,000 relatives massacred in the Río Sumpul. …