Recover Them from Oblivion. Recover the Community’s Ability to Produce

Cristina Lescano and El Ceibo

Some El Ceibo staffers, with Cristina (far right), transport recycling material. Photo by El Ceibo staff.

Lower-income sectors (LIS) often face tough obstacles and tensions that make it hard to act collectively. But a small group of people, made up of 40 families in a poor Buenos Aires neighborhood, overcame those barriers and organized to change the conscience of residents in Palermo, a trendy Buenos Aires neighborhood. We are talking about a collective of garbage recyclers known as El Ceibo.

THE BEGINNINGS: ORGANIZED TO SURVIVE

In our neighborhood, Palermo, 1989, we used to get together while we tried to buy some groceries for our families, with seven women, all of us with our children; besides we all were outside the law, because each one of us were living illegally in houses that didn’t belong to us: we were okupas [slang for illegal squatters of abandoned houses], young and most of us single mothers, and we hardly had a buck to live… There was hyperinflation those days, the president Alfonsín resigned… We, or me, who cares, needed to make something….

Coming to Buenos Aires from southern Patagonia in the mid 80s, Cristina Lescano got a job at City Hall as a community worker, but lost it a few years later, due to political reasons. Jobless, and in the midst of hyperinflation, that’s how the story of cooperative founder and Palermo inhabitant Cristina Lescano begins. But from that beginning follows the story of a woman who decided to organize people like herself, and fight to improve their situation. Cristina taught women reproductive health and mobilized them to get free contraceptive pills. At the same time, she also started an organization to defend the houses they were occupying illegally, but which had been vacant since the end of the 70s, when the military government evicted its former residents because of a planned highway that was never constructed.

Cristina’s narration contains common elements: the abandoned highway project, the abandoned houses, and the abandoned poor people taking those houses to find some shelter. But always some people try to do something to halt the cycle of neglect. That’s how the story of Cristina and the origin of El Ceibo began.

Throughout the late 80s and early 90s, El Ceibo created a network of grassroots groups to defend the illegal occupants of the otherwise vacant houses, even working with the Buenos Aires city administration to form the network. In the process, the scope of its activities grew, providing social support to single mothers and poor families by giving them a shared place to express their problems, helping them obtain ID cards that would allow them access to social and other services, and helping them get scholarships for their kids.

THE LATE 90S: STRATEGIES TO GENERATE INCOME

As we couldn’t find a job for years, cartonear was the only chance to get some bucks.

In the late 90s, the activities of this loosely institutionalized group continued to evolve as the economic situation in the country became increasingly unstable with increasing rates of unemployment and poverty. Many LIS families and groups began to see garbage collection as a survival strategy to earn some cash. Cartoneros dug through the trash to rescue almost anything that could be recycled and sold to middlemen. This activity was prohibited by law, so the cartoneros or cirujaswere forced to work by night, in small groups or individually, usually paying bribes to local authorities.

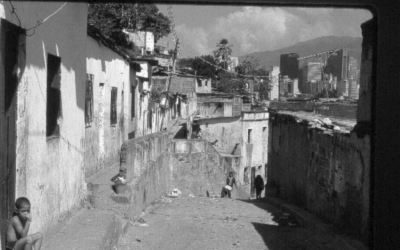

The garbage might be said to be improving the neighborhood. Once a solidly middle class neighborhood with sprawling houses on the outskirts of the city, a large section of Palermo became the trendy Palermo Soho in the late 90s, reminding visitors of the New York Soho, the Barrio Gotico of Barcelona or Boulevard Saint Germain des Prés in Paris. Cristina remembers silence and the singing of the birds as part of the landscape of her childhood Palermo, an area loved by Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges.

As the Argentine economy became nowhere-stagnated-land, with high rates of unemployment and poverty, some people living in Palermo began to notice those changes taking place in their backyards, and became receptive to initiatives like that of El Ceibo. Recycling has now become “cool” and something one should show off to one’s neighbor.

THE VALUE CHAIN: JUST A FEW NUMBERS OF A BIG BUSINESS

The garbage always pays well… There’s a lot of money and interest in the garbage.

But first, let’s examine the business of recycling itself. Cartoneros (also known as cirujas) gather and classify recyclable items such as paper, glass, metals, or clothes from residential and office trash, and then sell it to the depositero, or store man; recycled and processed material is eventually sold as raw materials to companies.

In Buenos Aires, 4500 tons of garbage are produced every day. The six waste collecting corporations that operate in the city take around 85% of it. Most recyclable trash is gathered up by those informal workers, the 10,000 to 25,000 cartoneros of the Buenos Aires metropolitan area, who receive an average of US$ 60 per ton collected. The next step in the value chain (depositero) adds a 15% margin. In a highly concentrated market, processors earn about US $ 400 per ton. According to some estimates, the cirujas as a whole take in US $ 30 million yearly, and the entire business produces US$ 150 million (La Nación, 6-25-2006), only taking into consideration the paper-related market in Buenos Aires.

Needless to say, cartoneros don’t pay taxes and the rest of the actors move in a legal twilight zone, with the acquiescence of some authorities.

THE ORIGINAL IDEA

That’s when I thought ´Why don’t we work together to get a better price for what we sell, while we take care of the environment´?

If the cartoneros could involve neighbors in the cooperative project, teaching them to separate organic from non-organic waste, Cristina explains, “then collecting it from their homes once or twice a week, we wouldn’t break the law, and later, we could put all the garbage together and take that to our galpón [storehouse] so we can clean the waste and have more economy of scale—one thing is the result of one family working; another is the production of 40 people—and sell it at a better price… we also can negotiate better.” That was the starting point for Cristina.

Nevertheless, the idea faced resistance: “As we didn’t know how to organize the work collectively, or didn’t have the money, we had to get in contact with a crowd of people to help us… It was hard because of the law, and because we were cirujas. Then, what to do? We needed to go out and beat the prejudice, both of the rich and the poor people.”

…AND HOW THE LAW LED TO INNOVATION

I realized that the garbage belongs to the one that produces it.

Informal recycling activity in Buenos Aires was illegal because the garbage on the streets belonged to city-contracted waste-collecting companies. Cirujas were pressed both by the law and by those public utilities firms that saw them as competitors. But Cristina thought they could use the legal framework as an opportunity to win potential clients’ loyalty: “We knocked on their doors, and as they saw us in Palermo every day for years, working in the light; thus they could trust in us.”

THE PROJECT

Now that we have the big picture in mind, we’ll see how El Ceibo works: Ten El Ceibo promoters canvass the pilot zone, a hundred block area with some 56.000 residents. They explain the benefits of recycling, the mission of El Ceibo (recycling both people and garbage), how the neighborhood could help the LIS to earn its money productively, and how to separate inorganic from organic waste. Cooperation grew from a hundred clients in 2001 to around 900 clients at present. El Ceibo´s number of providers increased after it began to collaborate with Greenpeace Argentina in a program called Basura 0, intended to promote new legislation in Buenos Aires regarding solid waste management policies. That alliance, which led to the passage of a law in 2005, was a hallmark for El Ceibo’s popularity.

Now, if the neighbor agrees, one of the 15 recuperadores stops by the house on a regular basis with his/her carrito, and takes the waste to El Ceibo gathering point in a storefront. Those recuperadores visit almost fifty clients every working day. As the recuperadores collect the solid waste from the homes and not from the streets, they aren’t breaking the law.

Inorganic waste is brought to a central point and then trucked to the galpón, where eight acopiadores separate, clean, and start the recycling process. After that, the waste is sold to specialized recyclers. The logistic-administrative duties are assigned to six persons, mostly members of the Administrative Council, the cooperative’s governing body. El Ceibo takes in US$ 32,000-36,000 yearly for the recycled materials. Each of the 40 members earns from US$ 1,400 to US$ 2,900 per year, an amount which includes a city government subsidy.

WORKING TOGETHER

We the cirujas aren’t used to work together, we don’t know how to work in a group, we needed to do that if we wanted to survive… It was hard for us to act collectively

Despite the large numbers of cirujas, they weren’t used to working together or presenting a united front in the agenda-setting process with other waste-stakeholders. It is hard, Cristina says, and we believe it: the city government office in charge of solid waste management that monitors the cartoneros says that there are just five cooperatives in Buenos Aires, employing 110 persons (around 1% of the cartoneros), even though there are thousands of individual cartoneros working in the city.

El Ceibo, one of the few cooperatives that has managed to organize, emerged as a collective actor in the first part of the value chain of the garbage collection-disposal process. They could only accomplish this over time, Cristina says when asked about the project’s resilience, “because we know each other from a long time, now our children are working as promoters or recuperadores, and the neighbors know us for a long time.” In this process, cirujas took on a new economic role: recuperadores urbanos, urban recyclers.

ALLIANCES: LEARNING TO WORK TOGETHER, WORKING TO LEARN TOGETHER

I always thought: if we want to make it, we need to open up ourselves…it was strange for us to work with Americans, Europeans, foundations, politicians, but I think it was stranger to them, to see the way we, the poor, work. It was fine because we learned from each other. It is so useful, for us certainly… I think it was useful for them too… but the rich don’t trust in the poor.

The cooperative managed to act with continuity and collectivity, not only because of the strong ties binding its members; its social capital; but, as Cristina concludes, “because we are open to everyone who has something that can be useful to us: whether it is money, experience, networking or political clout.”

Examples of alliances include work with Asociación Conciencia that provided training to El Ceibo on how to build an institutional and unified discourse for negotiating with local authorities; Greenpeace Argentina on how to work with the media and get visibility for the group; CLIBA (a waste collecting company); the World Bank, and more recently, AVINA, with its support for the production of crafts and artwork using recyclable materials. El Ceibo showed openness to alliances, but with two conditions: “as long as you don’t use me politically and we understand how to take advantage of your help, you’re welcome,” Cristina asserts.

FIRST RECOVER THE PEOPLE, THEN RECOVER THE GARBAGE

“How did we start with this project? In the end of the 1990s, laws passed by the dictatorship that governed the country said the garbage on the streets belonged to the firm that collected it. This led us to develop the following strategy: to pick up the garbage in the door of our clients voluntarily, instead of the usual method of the cartoneros: picking up the waste from the garbage bags that neighbors leave on the streets… We are closer to our clients because of our strategy, and despite the laws having changed, our type of relationship with them remains the same… From the very beginning we were driven by the same principle: Recover the people, and then recover the garbage.”

“Society changed after the 2001-2002 economic and political crisis. It is more open to support this kind of initiative. [Also] we opened our minds to working with people outside the cartoneros. In this sense, if the one who has the money wants to give us anything to make corporate social responsibility {sic}, it is welcome because we need the resources… the sole thing that we don’t want when it comes to making an alliance, is to be used politically, or to be eaten by our partners… In the end, a cooperative has to work and plan its strategy as corporations do, regardless of its legal status.”

— Cristina Lescano, President of El Ceibo

“Many of the people working here started the bond because we treated the problem of the okupas [illegal occupants of the houses], but soon we all realized that if we didn’t work, we couldn’t make it. It was so hard to change the minds of the poor people working here, with almost no concept of the duty, with no previous formal work, or not having any formal activities for a long time… We follow Cristina in everything she decides. Some times we discuss about this or that, but in the end, what can I tell you? Cristina la tiene muy clara con esto {has it right},”

— Alfredo Ojeda, El Ceibo promoter, and Valeria Corbalán, in charge of the cooperative’s administrative affairs.

Recover Them from Oblivion. Recover the Community’s Ability to Produce

Cristina Lescano and El Ceibo

By Gabriel Berger and Leopoldo Blugerman

Los sectores de bajos recursos (SBI) a menudo enfrentan severos obstáculos y tensiones para actuar colectivamente. Pero un pequeño grupo conformado por 40 familias de un barrio de Buenos Aires, sobreponiéndose a esas barreras, se organizó para cambiar la conciencia de los residentes de Palermo, un barrio porteño de moda.

LOS INICIOS: ORGANIZÁNDOSE PARA SOBREVIVIR

En Palermo, nuestro barrio, en 1989, solíamos juntarnos mientras tratábamos de hacernos de comida, etc. Éramos siete mujeres, todas con nuestros chicos. Estábamos afuera de la ley porque éramos “okupas”, es decir, que vivíamos en casas que no nos pertenecían legalmente y que estaban abandonadas. Imaginate: jóvenes, y muchas de nosotras además siendo madres solteras, apenas si teníamos para vivir… Era una época de hiperinflación, el presidente Alfonsín acababa de renunciar… Nosotras, o yo—a quién le importa—necesitábamos hacer algo…

Arribando a Buenos Aires desde la sureña Patagonia a mediados de los 80, Cristina Lescano obtuvo un trabajo en el Concejo Deliberante de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, desempeñándose como trabajadora social. Pero perdió ese puesto unos años después por razones políticas. Sin empleo, y con el fantasma hiperinflacionario de fondo, así es como se inicia la historia de la fundadora de la cooperativa y habitante de Palermo. Con este marco comienza la trayectoria de una mujer que decidió organizar a gente como ella y luchar para mejorar su situación, inicialmente, enseñando salud reproductiva y movilizando a las madres para obtener píldoras anticonceptivas. Al mismo tiempo, comenzó a estructurar una organización para defender las casas que ilegalmente estaban ocupando, pero que habían estado vacías desde los 70, cuando el gobierno militar desahució a sus anteriores ocupantes porque por esa zona se tenía planeado construir una autopista que finalmente nunca se erigió.

El abandono parece ser un hilo conductor a través de la historia de Cristina: el proyecto abandonado de la autopista, las casas abandonadas y las personas pobres tomando esos hogares para encontrar algún tipo de refugio. Pero siempre alguien intenta hacer algo para evitar el ciclo del olvido. Así entonces es como comienza la historia de Cristina y el origen de El Ceibo.

A través del final de los 80 y el principio de la década del 90, El Ceibo creó o se integró a una red de grupos de base para defender a los ocupantes ilegales de las casas que de otro modo estarían desocupadas, inclusive trabajando con la administración de la ciudad de Buenos Aires para formar esta red. Durante este proceso, el alcance de sus actividades creció, proveyendo apoyo social a madres solteras y familias pobres, dándoles un lugar compartido para expresar sus problemas, ayudándolos a obtener documentos de identidad que les permitiesen acceder a servicios sociales y otros, y ayudando a sus hijos a obtener becas escolares.

FINES DE LOS 90: ESTRATEGIAS PARA GENERAR INGRESOS

Como no podíamos obtener trabajo desde hace años, cartonear era nuestra única oportunidad para sacar unos mangos.

Al final de la década anterior, las actividades de este grupo débilmente institucionalizado continuaron evolucionando mientras la situación en el país se fue inestabilizando cada vez más, con crecientes tasas de desempleo y pobreza. Muchas familias y grupos de SBI comenzaron a ver a la recolección de basura como una estrategia de sobrevivencia para obtener algún ingreso. Los cartoneros escarbaban en la basura para rescatar lo que sea que se pueda reciclar y vender a intermediarios. Esta actividad estaba prohibida por ley, así que los cartoneros estaban forzados a trabajar por la noche, en pequeños grupos o individualmente, usualmente pagando sobornos a algunas autoridades locales.

Se podría decir que por esas fechas en el barrio la basura parecía estar mejorando. Formando parte de lo que alguna vez había sido un barrio de clase media con casas bajas y amplias lejos del centro, una parte de Palermo se transformó a fines de los 90 en el trendy Palermo Soho, haciendo recordar a los visitantes al Soho de New York, al Barrio Gótico barcelonés o a la zona próxima al Boulevard Saint Germain des Prés en París. Cristina recuerda el silencio y el canto de los pájaros como algo inseparable del viejo Palermo, un área amada por uno de los más prestigiosos escritores argentinos, Jorge Luís Borges.

Mientras la economía argentina se transformaba en una estancada tierra de nadie, con altas tasas de desempleo y pobreza, alguna gente viviendo en Palermo comenzó a darse cuenta de los cambios que se estaban desarrollando en sus calles, y se interesó en iniciativas como la llevada a cabo por El Ceibo. Reciclar ahora era cool, por lo que era algo que debía hacerse para aparentar ante los vecinos.

LA CADENA DE VALOR: SÓLO UNOS POCOS NÚMEROS DE UN GRAN NEGOCIO

La basura siempre paga bien… hay un montón de plata e intereses alrededor de la basura.

Pero, primero, examinemos el negocio del reciclado en sí. Los cartoneros (también conocidos como cirujas) recogen y clasifican elementos reciclables como papel, vidrio, metales o ropa, provenientes de basura residencial y de oficinas, y luego los venden al depositero, que se suele especializar en un tipo de material, quien es el que acapara el producto; la basura reciclada y procesada eventualmente se vende como materia prima a las diversas empresas.

En Buenos Aires son producidas diariamente unas 4.500 toneladas de basura. Las seis empresas recolectoras que operan en la ciudad retiran de las calles el 85% de estos residuos. La mayor parte de la basura reciclable es recolectada por estos cartoneros (unos 10.000 a 25.000 en el área metropolitana de Buenos Aires), que reciben un promedio de US$ 60 por tonelada. El próximo paso en la cadena de valor (depositero) le agrega un margen del 15%. En un mercado altamente concentrado, los procesadores ganan US$ 400 por tonelada. De acuerdo a algunas estimaciones, los cirujas en conjunto ganan US$ 30 millones anuales, mientras que todo el negocio produce US$ 150 millones (La Nación, 25-6-2006), solamente considerando el mercado relacionado al papel en Buenos Aires.

Sin que haga falta aclararlo, los cartoneros no pagan impuestos, y el resto de los actores de la cadena se mueve en un claroscuro legal con la aquiescencia de algunas autoridades.

LA IDEA ORIGINAL

Ahí fue cuando pensé ´¿Por qué no trabajamos juntos para conseguir un mejor precio por lo que vendemos mientras cuidamos el medioambiente?´

Este fue el punto de partida de Cristina: Si los cartoneros podían involucrar a los vecinos en el proyecto cooperativo, enseñándoles a separar en origen la basura orgánica de la inorgánica, explica, “y luego recolectásemos de sus casas la basura inorgánica una o dos veces a la semana, no romperíamos la ley. Y si después de eso acopiásemos toda la basura recolectada y la pudiéramos llevar a nuestro galpón de manera de que podamos limpiarla y lograr más economía de escala –dado que una cosa es el resultado de una familia trabajando, y otra es la producción de 40 personas-, para recién luego venderla a mejor precio,… podríamos, además, negociar mejor”.

De todos modos, la idea enfrentó resistencias: “como no sabíamos cómo organizarnos para trabajar colectivamente, y no teníamos el dinero para hacerlo, teníamos que entrar en contacto con un montón de personas para que nos ayuden… Eso fue difícil por la ley, y porque éramos cirujas. ¿Entonces, qué hacer? Necesitábamos salir a hacerlo y derrotar al prejuicio, tanto de los ricos como de los pobres”.

…Y CÓMO LA LEY LLEVÓ A LA INNOVACIÓN

Me di cuenta que la basura pertenece a quien la produce.

La actividad de reciclado informal era ilegal porque la basura en las calles pertenecía a las compañías de recolección de basura contratadas por la ciudad. Los cirujas estaban presionados, así, tanto por dicha ley como por estas firmas, que los veían a ellos como competidores (dado que se les pagaba por tonelada recolectada). Pero Cristina pensó que podrían usar el marco legal como una oportunidad para ganar la lealtad de los potenciales clientes: “Golpeábamos en sus puertas, y como nos veían todos los días en Palermo desde hacía años, trabajando en la luz, entonces pensamos que podían confiar en nosotros”.

EL PROYECTO

Ahora que tenemos la fotografía mental del contexto, veremos cómo trabaja El Ceibo: Diez promotores de la cooperativa recorren la zona piloto, área de 100 manzanas con unos 56.000 residentes. Dichos promotores explican los beneficios del reciclaje, la misión de El Ceibo (Recuperar las personas para luego recuperar la basura), cómo el vecindario podría ayudar a los SBI a ganar su dinero productivamente, y cómo separar los residuos inorgánicos de los orgánicos en origen. La cooperativa creció de unos 100 clientes en 2001 a los aproximadamente 900 que tiene en la actualidad. El número de los proveedores de El Ceibo aumentó luego de la colaboración con Greenpeace Argentina en un programa llamado Basura 0, cuya intención era promover una nueva legislación en la ciudad de Buenos Aires en lo concerniente a políticas de gestión de residuos sólidos. Dicha alianza tuvo un impacto muy alto a favor de la popularidad de El Ceibo, y además coadyuvó a la aprobación de una ley, en 2005, que cambió el marco legal con el que se había encontrado la cooperativa al inicio de sus actividades.

Luego, si el vecino está de acuerdo, uno de los 15 recuperadores pasa regularmente por su casa con el carrito, y se lleva los residuos al punto de recolección en la puerta del local de El Ceibo. Estos recuperadores visitan alrededor de 50 clientes por día de trabajo. Así, como los recuperadores recolectaban los residuos sólidos de las casas, y no de la calle, no estaban violando la ley.

Finalmente, toda la basura inorgánica es llevada al galpón, en el cual ocho acopiadores separan el material, lo limpian, y comienzan con el proceso de reciclaje. Luego de eso, el residuo es vendido a recicladores especializados en cada producto. Las tareas logístico-administrativas son llevadas a cabo por seis personas, la mayoría de ellas miembros del Consejo de Administración, el cuerpo de gobierno de la cooperativa. Resultante de dichas ventas, los ingresos anuales de El Ceibo oscilan entre los US $ 32.000-36.000. A su vez, cada uno de sus aproximadamente 40 miembros tiene un ingreso anual de entre US$ 1.400 a US$ 2.900, un monto que incluye un subsidio del gobierno de la ciudad de Buenos Aires.

TRABAJANDO JUNTOS

Nosotros, los cirujas no estábamos acostumbrados a trabajar juntos, no sabíamos cómo trabajar en grupo, y necesitábamos hacerlo si queríamos sobrevivir… Fue difícil actuar colectivamente.

A pesar de la enorme cantidad de cirujas, los miembros de este colectivo no estaban acostumbrados a trabajar juntos, o presentar un frente unido en el proceso de fijación de la agenda de la basura junto con otras partes interesadas (stakeholders). Es difícil, dice Cristina, y lo creemos: la oficina del gobierno porteño encargada de la gestión de los residuos sólidos que tiene a su cargo la relación con los cartoneros dice que, con residencia en la ciudad de Buenos Aires, sólo hay cinco cooperativas, empleando unas 110 personas (alrededor del 1% de los cartoneros), aun cuando hay miles de cartoneros individuales trabajando en la ciudad.

El Ceibo, una de esas pocas cooperativas que se las arregló para organizarse, emergió como un actor colectivo en la primera parte de la cadena de valor del proceso de recolección y disposición final de la basura.

ALIANZAS: APRENDIENDO PARA TRABAJAR JUNTOS, TRABAJANDO PARA APRENDER JUNTOS

Siempre pensé: Si queremos avanzar, necesitamos abrirnos… Fue extraño para nosotros trabajar con norteamericanos, europeos, fundaciones, políticos, pero creo que fue más extraño para ellos el ver la manera en que los pobres trabajamos. Estuvo muy bien porque aprendimos uno del otro. Fue muy útil, al menos para nosotros… aunque pienso que para ellos también… pero el rico no confía en el pobre.

La cooperativa se las ingenió para actuar con continuidad y colectivamente, no sólo por los fuertes lazos que unen a sus miembros, su capital social, sino también, como concluye Cristina, “porque estamos abiertos a cualquiera que tiene algo que nos pueda ser útil, sea dinero, experiencia, capacidad de establecer redes o contactos políticos”.

Entre los ejemplos de alianzas que estableció la cooperativa podemos mencionar su trabajo con Asociación Conciencia, que les proveyó entrenamiento en cómo construir un discurso institucional y unificado para negociar con las autoridades locales, con Greenpeace Argentina, sobre cómo trabajar con los medios de comunicación y darle visibilidad al grupo, con CLIBA (una empresa recolectora de residuos), el Banco Mundial y, más recientemente, con AVINA, que los apoya en la producción de materiales y artesanías usando materiales reciclables. En definitiva, El Ceibo ha demostrado apertura a las alianzas, pero con dos condiciones, afirma Cristina: “en tanto no nos uses políticamente, y entendamos cómo sacar provecho de tu ayuda, sos bienvenido”.

PRIMERO RECUPERAR A LA GENTE, LUEGO RECUPERAR LA BASURA

“¿Cómo comenzamos con este proyecto? Todavía a fines de los 90 las leyes que había de la época de la dictadura militar decían que la basura en las calles pertenecía a la empresa que la recolectaba. Esto nos llevó a desarrollar la siguiente estrategia: recoger la basura en la puerta de nuestros clientes voluntariamente, en vez del método usual de los cartoneros, que es recolectar los materiales reciclables revolviendo las bolsas de basura que el vecino deja en la calle… Estamos más cerca de nuestros clientes a causa de la estrategia que tenemos, y a pesar de que las leyes sobre la basura han cambiado, las características de nuestra relación con ellos se han mantenido igual… Desde el inicio nos guió el mismo principio: Recuperar a la gente y luego recuperar la basura.”

“La sociedad cambió luego de la crisis política y económica de 2001-2002. Está más abierta a apoyar este tipo de iniciativa. [Además] abrimos nuestra cabeza para trabajar con gente que está fuera del ámbito de los cartoneros. En este sentido, si el que tiene dinero quiere darnos algo para hacer responsabilidad social corporativa [sic], es bienvenido porque necesitamos los recursos… lo único que no queremos en todo lo que sea formar una alianza es ser usados políticamente o ser comidos por nuestros socios… En definitiva, a pesar de su estatuto legal, creo que una cooperativa tiene que trabajar y planificar su estrategia como hacen las empresas.”

— Cristina Lescano, Presidenta de El Ceibo.

“Mucha de la gente que está trabajando acá comenzó el vínculo porque tratábamos el tema de los ´okupas´ [ocupantes ilegales de casas], pero enseguida nos dimos cuenta que si no trabajábamos productivamente no íbamos a poder salir adelante. Fue difícil cambiar las ideas de la gente pobre trabajando en El Ceibo, que no tenía casi experiencia de un trabajo formal previo, o estaban desempleados formalmente desde hacía mucho tiempo… Seguimos a Cristina en todo lo que decide. Algunas veces discutimos sobre tal o cual cosa, pero al final, ¿qué te puedo decir? Cristina la tiene muy clara con esto.”

— Alfredo Ojeda, Promotor de El Ceibo, y Valeria Corbalán, A cargo de tareas administrativas.

Gabriel Berger is a professor at Universidad de San Andrés in Buenos Aires (UdeSA) and director of the Graduate Program in Nonprofit Organizations. He leads the SEKN team at UdeSA.

Leopoldo Blugerman is a research assistant on the SEKN team at UdeSA. He holds an M.A. in International Relations from Bologna University, Italy.

Related Articles

NGOs and Socially Inclusive Businesses

In the nonprofit world, social mission and market-based operations and financing are seen much too often as a contradiction in terms. Relating and aligning both dimensions of organizational performance …

The Role of Government

In current discussions of market initiatives oriented towards low-income populations around the world, the government is often like the empty chair around a table. We all know its occupant exists …

Market Initiative with Low-Income Sectors

Angela, a power inspection crew member at AES-Electricidad de Caracas (AES-EDC), was inspecting an energy tower installed near a Caracas barrio. Nearby dwellers tapped the tower to get free power. …