Researching Latin America: from Under Informed to Overwhelmed

A Personal Chronology of Changed Communication

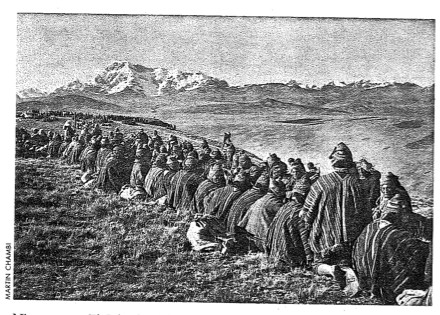

Martin Chambi, the first indigenous pho- tographer in Latin America (1891- 1973), captured this image of peasants on a lunchtime break by the snow-covered Ausangate mountain, Ocongate, Cuzo, Peru, 1934. Chamb’s work can be found at chttp://garnet. berkeley.edu/~ dolorier/Chambidoc. htmls

The instant outpouring of Web information on the Pinochet case got me to thinking about communications on my first trip to Chile during the Allende presidency. I was armed for Ph.D. research with a portable typewriter twice as big as a contemporary laptop and carbon paper. Before the trip it was impossible to keep up with rapidly changing Chilean politics.The New York Times had one reporter covering all of South America. Once in Chile communications with home were either slow and uncertain (mail – a week to ten days) or somewhat faster, exceedingly expensive, and also uncertain (telephone). A small group from the U.S. put out a monthly newsletter in Spanish with information about the antiwar movement in the U.S. We had friends in the U.S. mail clippings, so our “news” was stale. (Ed. Note: The group was portrayed in the film Missing.)

Calls to my girl friend in Boston would take thirty minutes to four hours to go through (if they made it). Our relationship was not going well. Phone fights would lead to mutually enraged silences – a dismal irony. The one who would break the silence was not the peacemaker, but the one paying for the call.

Around 1979, I began to analyze U.S. media coverage of the emerging crisis in Central America. Few U.S. scholars had background in Nicaragua or El Salvador. Though I was hardly one of them, I thought that the rapidly expanding coverage was off base. Alternative sources of information were few and far between. People returning from short trips could be debriefed, journal articles gradually began to emerge, and I began to travel to the region.

But by the standards of a decade earlier media coverage was massive. In 1982 the Times had 613 stories on El Salvador, 149 of them in March during the Constituent Assembly elections crucial to U.S. policy. In 1972 the Times had had 4 tiny stories on the crucial Salvadoran election. From 1970 – 1978 network evening news shows devoted 3 minutes to El Salvador, but eleven hours in 1982 alone, according to a 1996 doctoral dissertation by David Krusé. By then TV stories were beamed by satellite in contrast to shipping films during the 1969 Honduras – El Salvador war. In a dramatic tableau, Tom Brokaw himself could be seen live scooping up shell casings from a firefight the dawn of Salvador’s 1982 election day. (Viewers were not informed that he was a five-minute drive from his luxury hotel.) Around then, I became apprehensive about my spending so many hours watching TV.

I typed articles on media coverage on an IBM Selectric. A major advance over my old portable, the Selectric permitted error correction (backspace, lift black ribbon, lift white ribbon, overstrike, lower ribbons, strike proper key). I bought one of the first VCRs to tape the evening news; it cost $900. By 1983 I had joined the personal computer revolution with a “portable,” Kaypro, the Model T Ford. The keyboard attached to the computer with its 5″ screen, but transporting it was like carrying a suitcase filled with bricks. It had 64K of Ram. With no hard drive programs had to be loaded in, used, and then removed. Sound primitive? It seemed like a miracle.

In May 1989, I helped launch an effort through a new group called Hemisphere Initiatives to monitor the Nicaraguan elections, along with the United Nations, the Carter Center, and the Latin American Studies Association (LASA). Typewriters were obsolete (though not in Nicaragua) and the UN, not an organization that stints on equipment, had radios in their 4X4 Land Cruisers that could reach Managua, New York or South. Fax machines were available, though costly. LASA teams had truly portable laptops with 40 Mg hard drives and could draft and edit reports while together in Managua.

But if our Boston office needed a UN election report it meant a trip to the UN Managua office, one-page-at-a-time photocopying and faxing over fragile phone lines.

In 1989, e-mail was becoming common, but it was virtually non existent in Nicaragua. By 1993 e-mail was ubiquitous in the U.S. and common in Central America. On a Fulbright in El Salvador in 1993-94 I could down load text documents, though at 1200 baud per second they had better be short. Phone lines were much improved. Indeed MCI and AT&T were selling Salvadorans a calling card which would put them in touch (collect!) with their loved ones in LA, enhancing personal contact while also cutting the flow of remittances.

By 1994, Central America had dropped off the mainstream media’s agenda. But back in the U.S., I could now download three dozen pages a week of news on El Salvador posted on e-mail news conferences, and “talk” with friends in Central America (though there could be a twelve hour delay in transmission.) In 1981 one scraped for information, by 1994 managing it was the central problem. Then came Chiapas, a rebellion with a keen sense of the media and which used the internet to circumvent news media blocks in Mexico. Chiapas received major U.S. media attention, but that was small in comparison to an absolute explosion in Chiapas e-mail traffic.

And then came the Web. Here’s a site with 34 Latin America magazines and dailies from 14 countries. Want recent election results? The latest IDB economic data on each country? How about reports on wine production in Argentina? Coffee futures? Need a book on Colombia held only by two libraries in the U.S? A journal article can be searched and faxed within hours (for a hefty fee), though faxing now suddenly seems primitive compared to downloading at 56K. And 56K on my home modem seems tediously slow compared to the new fast wires at the University.

I’ve been doing research on the peace process in Colombia. I can get coverage not just from the Bogotá daily, El Tiempobut from various regional Colombian papers. With a meeting between newly elected President Pastrana and the guerrilla chief “Tirofijo,” a guerrilla before Pastrana was born and then Pastrana’s trip to Cuba events have been hopping. For the January 16-18 weekend, I downloaded 22 news articles just from El Tiempo and the magazine Semana.

Why leave home? Sometimes I even get the feeling that I don’t have time to go to Latin America because I will be missing such a huge flow of graphics and data from my many “book marked” locales and e-mail conferences and communiqués that I could never catch up on my return. Indeed, I may never have to go outdoors again, not even to the library, and I could order groceries from Home Delivery.

But then I discovered this past July in my hotel in Bogotá that it had a “Communications Center” replete with fax machines, computers, e-mail, the web. Caught in the interminable traffic of Bogotá’ on the way to an interview I fretted that I was wasting time not being “plugged in” at my hotel.

Two days later I was in Barrancabermeja, a hot, muggy oil refining center in the mid regions of the Magdalena River, an area being contested by about every armed and unarmed group in Colombia. I’m sure e-mail was around, but I didn’t find it. On the weekend, I was surprised at having great difficulty making an international call from my hotel where the phones, in general, did not work well. At mid morning, I was walking with a Colombia colleague to an interview. I was sweating. I could smell the refinery. I could smell the smells of the outdoor market. We passed a newly painted, old style, hotel on the banks of the river, the former headquarters of Tropical Oil Company my colleague told me. Small boats plied the muddy Magdalena. Some were carrying refugees from downstream fleeing from attacks by rightist paramilitaries on their villages.

We attended a meeting of local political and social service groups preparing for an influx of several thousand refugees. There was a mixture of urgent intensity and banter in the room as several fans roared. At lunch we interviewed a Jesuit economist, Fernando de Roux, who is helping run an internationally funded development project in the Middle Magdalena region. We ate rotisserie chicken at plastic tables with our hands in plastic bags to fend off the grease. He had reams of data in his head ranging from the equivalent of a GDP for the region (approximately that of Spain on a per capita basis, but the money doesn’t stay home); to the rules of life in areas controlled, more or less, by guerrilla groups, to the politics of mediating kidnapping releases. He rapidly sketched on a napkin a map of the municipalities touching on the Magdalena over a 150 mile stretch and which groups were shoving and hauling in which places. We met some of the refugees, then moved on to other interviews. In the evening we met with Archbishop Prieto in the cool sanctuary of his residence and heard his nuanced analysis of the political situation. Afterwards in the mild evening air we saw couples strolling on a Saturday night. The refinery gas jets were flaring in the sky. We made our way to an open-to-the-street restaurant for cold Ãguilas, steaks and fries. You can’t get these things on the Web.

Winter 1999

Jack Spence teaches in the Political Science Department at U Mass Boston and heads Hemisphere Initiatives, a research group that analyzes peace processes. He served as President of the New England Council of Latin American Studies last year.

Related Articles

Linking Latin America

I have captured images of such seemingly disparate subjects as Mennonite immigrants to Mexico, Latina contestants for Selena standings, the Pope in Cuba, and traditional Sunday serenatas…

A Violence Called Democracy

As any journalist or diplomat who has spent time in Guatemala will attest, no group there is more difficult to penetrate than the Guatemalan Armed Forces. As much a caste as an institution, the…

The Public Face of Cyberspace

Imagine a network that spans the world. A network that delivers — invisibly and inexpensively — the myriad bits of information that will undeniably be the key to prosperity in the 21st century…