Resistance and Reform

Power to the People?

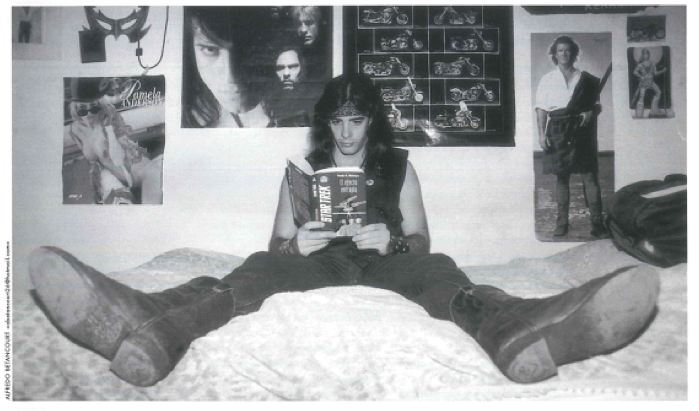

Science fiction writer José Miguel Sánchez “Yoss” is the founder of “Maria’s Patio,” on alternative lifestyle space.

A university chemistry professor in Havana quietly mixes chemicals-paid for by the state- for a local photographer. The photographer in turn sells some of his pictures to a Spanish tourist agency, but bills his client through a friend, who has a licensed publicity firm. His friend, who does some travel on work-related business, in turn uses money left from his last trip’s per diem to fix his kitchen floor with tiles purchased in the black market.

These kind of small-and almost routine- activities in Cuba reflect sometimes ineffective government efforts at control. But they also underline how islanders evade official rules and regulations quietly and often illicitly, in ways that have the effect-although not necessarily the intent-of remaking island socialism.

When the Soviet bloc collapsed nearly ten years ago, many expected Cubans to take to the streets and bring the government down. The economy had shrunk almost overnight by some 40 percent, because the island had depended on the Communist countries for some 85 percent of its trade and most aid. Furthermore, Communism had been delegitimated in the countries that had been the country’s allies for nearly thirty years. Critics say the rebellion did not take place because of government repression, while sympathizers point to the democratic, distributive, and egalitarian nature of Castro’s regime.

Both interpretations contain elements of truth (and non-truth) but neither adequately accounts for why Castro weathered the storm. The answer may lie elsewhere. Islanders disobey aspects of socialism they dislike, not in the abstract but as experienced concretely, and the government has responded with reform. How have people shaped the new Cuba, and what limits are there to government willingness to modify socialism as islanders knew it?

Society and Its Discontents

Experiencing deep cuts in living standards, islanders defied the law and official exhortations. They did so mainly covertly, without attacking state socialism head on.

They did so, for one, in the world of work. They refused state calls to do fulltime or seasonal farmwork, even though urban employment opportunities plummeted with the economic recession. A food crisis arose when the government no longer could afford oil, pesticides, and food imports. Since Castro had massively educated the population, islanders no longer wanted to do back breaking manual labor, even if it offered them work and increased the food supply.

Cubans, whether formally employed or not, instead gravitated to illegal private economic activity, on a full or part-time basis. Despite state regulations, the self-employed sector came to involve an estimated third of the civilian labor force. Even people with secure jobs left to scheme on their own. Some of the independently employed even hired their own staff, also against the law. Under these circumstances, authorities in some provinces found they no longer had enough doctors and nurses, teachers and professors, to keep up the health care and education so fundamental to the revolution and its legitimacy.

Saints on the street

People were not calling for an end to socialism and a capitalist revolution. They were trying to make the best of a bad situation. They turned to private activity because the value of their official salaries plunged with the economic crisis and because they could charge in dollars for their work. The dollar dramatically increased in value as the value of the peso collapsed. Although dollar possession and transactions were illegal, the black market peso/dollar exchange rate rose to over 120:1.The official exchange rate stood at 1:1. The government essentially lost control over an emergent informal dollarized economy.

Cubans similarly sabotaged the distributive system. Because the new scarcities would have priced goods in an open market beyond most Cubans’ means, the government rationed most consumer goods to “equalize sacrifice.” However, a runaway black market in goods also evolved, because scarcities drove up the “real” market value of goods. Nearly everyone came to participate in the black market, often both as buyer and seller. Paradoxically, government control over the distributive system caved just when it officially increased. By 1993, the value of the black market purportedly exceeded the value of official retail trade. Off-the-books sales of foodstuff became the most widespread black market activity, but theft and pilfering of other goods, as well as bribery and corruption, reached record levels as well. With most of the economy state owned, the illegal activity entailed crimes against the state and the appropriation of state resources for private ends.

The formal political system managed to only partially channel grievances. Yet, even in this domain islander disobedience picked up. For example, islander involvement in the official mass organizations tapered off. Older Cubans withdrew their support both because subsistence became more time-consuming and because the groups did not adapt to their changing needs and concerns. The younger generation did not participate to begin with. They had never participated in movements smashing the Old Order and mainly knew only New Regime hardships. The organizations had little appeal to them. Islanders did not overtly challenge the groups (although there was discussion of merging the women’s and block organizations). However, in withdrawing their support they undermined organizational effectiveness. Since local block organizations ceased to function as adequate informal social control mechanisms, authorities had to form Rapid Response Brigades-government-sanctioned mobs- to quell neighborhood dissidence.

Covert electoral dissidence also increased. Although Castro turned national elections into patriotic plebiscites, into “a yes for Cuba” and a “rejection of the Helms Bill,” about 20 percent of the electorate refused to comply with this call for a “show of unity.” According to available evidence, one in five islanders either refused to vote for the entire official slate of candidates or spoiled or cast blank ballots. Occasionally, the protest went from covert to overt. On August 5, 1994, Central Havana became the scene of the first mass protest in Castro’s Cuba. One to two thousand angry citydwellers, young men above all, took the risk of publicly challenging the state. Protesters chanted anti-government slogans and looted stores. The protest occurred when the food supply reached rock-bottom.

Nonetheless, islanders turned more to religion than to politics. The new religiosity entailed cultural resistance, since the regime had become professedly atheistic since the early years of the revolution,. The resistance was all the more marked in that islanders turned to syncretic Afro-Cuban religions and, secondarily, to evangelical Protestantism, more than to orthodox Catholicism favored by the Hierarchy. One in five respondents in a 1994 Gallup poll admitted to attending church the preceding month. Hundreds of thousands of islanders also began to turn out for once-small church celebrations, often with santeria amulets. Santeria, which has a truncated religious hierarchy, is indigenous and national in focus, even if its roots lie in Africa. Evangelical Protestantism, although foreign in origin, also appeals because of its sect-like structure based on strong interpersonal ties. In turning to religion, the populace is contributing to a remaking of the socio-cultural order, more than they typically envisioned.

Government Responses

In response to the mounting covert disobedience that sabotaged state control over production and distribution, that eroded the moral and socio-cultural order, and that challenged regime legitimacy as never before, the government initiated a series of reforms. Many reforms legalized what islanders had taken to doing illegally or without official sanction.

Following the 1994 protest, Castro immediately opened up the possibility to emigrate. Some 33,000 islanders took advantage of the opportunity and left in make-shift boats. If the U.S. and Cuban governments had not agreed within a month to establish procedures and quotas, the number would have been even greater.

Authorities also modified economic policies. They stepped up material incentives to attract labor to agriculture, legalized certain types of self-employment (and gradually expanded the permissible types), decriminalized dollar possession, and set up peso-dollar exchange booths and dollar-only stores. They also transformed most state farms into cooperatives and began to pay a portion of salaries in a new currency that could be spent at new hard currency stores. They also opened private markets. While Castro continued to claim that he found capitalism repugnant, and that the reforms were “born of special needs,” not desire, socialism was broadened in words and deeds to include features of a market economy. He argued that the reforms were designed to defend and save, not transform, socialism.

Political changes took place as well, but they had less structural significance and were less tied to citizen defiance. The government introduced direct elections for provincial and national as well as municipal levels of governance. It brought together large groups of people to debate proposed policies and air grievances. It also oversaw a major shakeup in the commanding heights of key political institutions. Castro replaced old with young cadre to appeal to increasingly apathetic and disaffected youth. Whatever deepening of democracy these measures entailed, they were all within the contours of a Leninist party-state.

Moreover, Castro quite remarkably sought to coopt symbolically the August 5 protest. On the one year anniversary he claimed August 5 a “great revolutionary victory.” To further appropriate and redefine the symbolism of the protest, and transform it into a patriotic cause, he had the government organize a “Cuba Vive” manifestation, involving half a million islanders.

Dissidents overtly opposing the government, in general, met with less success. Their defiance crossed the boundaries of what officials considered permissible. Dissidents faced arrests, imprisonment, and house confinement, though typically for shorter periods than in the early years of the revolution. With no access to the officially controlled media, the dissident movement remains small and fragmented and without a mass base. Though Concilio Cubano dissident groups banned together, authorities prevented them from meeting publicly. Official constraints aside, scores of small illegal groups managed to continue to engage in a flurry of activity, and to meet with visiting dignataries during the November 1999 Ibero-American Summit in Havana. In this more internationally exposed context, the government responded with discreet but stepped-up low intensity repression, and then craftily diverted the popular imagination with Cuban-Venezuelan baseball game led by the respective heads of state.

Covert disobedience challenged regime legitimacy as never before.

Meanwhile, authorities became increasingly tolerant of the new religiosity. They themselves, in growing numbers, sought meaning in sacred beliefs and practices. Government tolerance picked up quite possibly because Castro recognized that Marx’s dictum that “religion is the opiate of the people” did not seem so bad at a time of severe duress.

Government responses followed no blueprint. Authorities responded at times with reform, but on other occasions with cooptation and repression. Indeed, as the pace of economic recovery slowed down at the millennium’s end repression picked up.

Covert forms of institutional noncompliance may be difficult to discern, but if they are not taken into account, the state appears much more powerful and society more passive than history has demonstrated. Islanders who have tried to make the best of the current crisis have contributed to a remaking of island socialism, intentionally and not. But their impact remains more tied to the economic and religious than political realm. Castro views market reforms as tolerable and under current conditions essential, but meaningful political reforms undoubtedly as threatening.

Winter 2000

Susan Eckstein, Professor of Sociology at Boston University, is Past President of the Latin American Studies Association and a DRCLAS Research Associate. She is also the author of Back from the Future: Cuba under Castro (Princeton University Press, 1994).

Related Articles

RFK Professor Roberto Schwarz

Roberto Schwarz, Robert F. Kennedy Visiting Professor this past semester, is one of the foremost Latin American intellectuals whose critical work spans 25 years. Students who took his Romance…

Reminiscences of the Botanical Garden at Central Soledad

The bus-it was Greyhound, I believe-took us all the way from Boston to Key West that summer in 1940. Then we boarded the ferry to Havana and finally the night train to Cienfuegos in the middle…

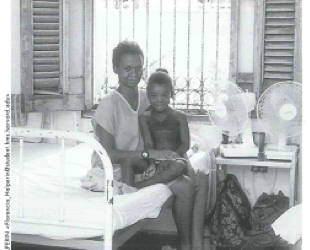

A Medical Student Looks at Cuba

Fresh off the plane, and already my interest was piqued as we drove out of the airport in Havana. I had just finished my first year at Harvard Medical School, and was in Cuba with a group of…