Rethinking Human Rights

Unshackling the Story

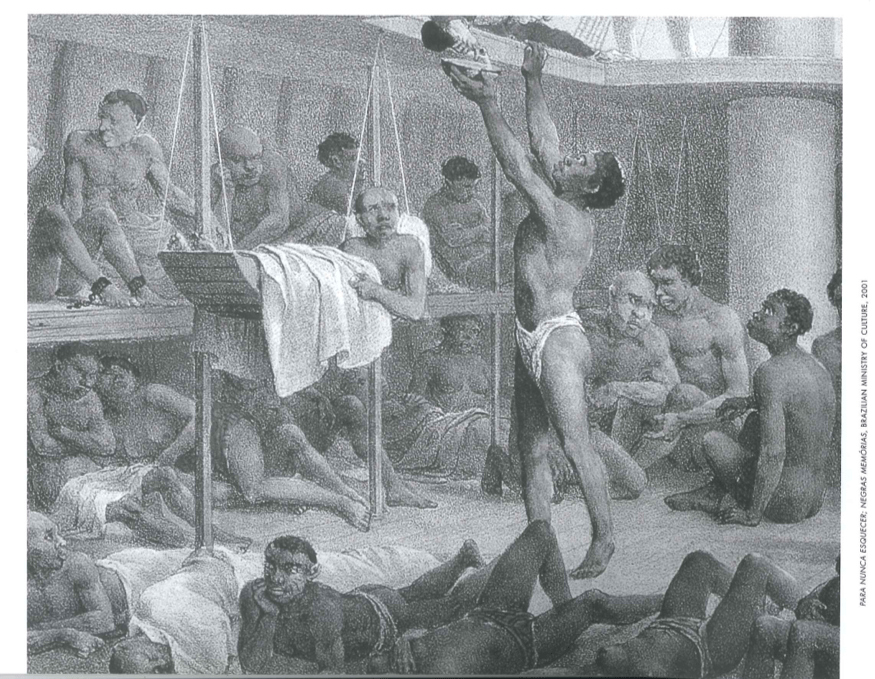

Johan Moritz Rugenda made this lithograph of a slave ship in 1835.

I sit in my Bogotá office, catching up with reading in international law. I sometimes wonder whether to bother. Here in Colombia, reality makes the language of human rights seem useless and stale one day—and absolutely necessary and definitive the next. Obfuscation has reached the point that some students in my international law class end up arguing against human rights because they perceive that it is does not sufficiently address the complexity of the Colombian conflict.

Perusing Harvard Law School professor David Kennedy’s recent article, “The International Human Rights Movement: Part of the Problem?,” I find a series of (polemical) hypothesis that may help evaluate the costs and benefits of using human rights discourse as the main contemporary vocabulary with which to pursue emancipatory objectives. Kennedy suggests that one of the problems of the effectiveness (or lack of) the human rights idea may be the blindness that its too abstract or too constrictive language conveys.

The article makes me wonder if, like Kennedy says, the human rights movement in Latin America requires a reassessment. One starting point might be examining the regional foundational story with its claim that the first “human rights defenders” emerged from a Catholic tradition—disregarding the role that these men played in supporting the conquest and colonization of Spanish America.

It is particularly compelling to revisit the arguments surrounding the legality of slavery authored by 16th- and 17th-century Jesuit, Dominican and Capuchin jurists and theologians. These religious thinkers framed their observations within a unified world-view seeking the “common good” and presupposed that the distinction between good and evil was inherent to human reasoning and that the correct (or just) view could thus be legitimately deduced. On the subject of slavery, the concrete concern was whether a person was detained and enslaved with a “just cause” but not if the institution was unjust or immoral in itself. Therefore, it was difficult to question the legitimacy of slavery since it was authorized by a number of theologians, ratified by the custom of centuries and recognized as part of the law of nations. Nonetheless, a debate on the legality of the enslavement process existed, accompanied by theological, philosophical, historical, economic and even ethnographic arguments.

The Spanish Dominican theologian, Domingo de Soto (1494-1560) produced one of the earliest observations on the dubious legality of African enslavement. Although he accepts the just cause argument for slavery, in Iustitia et lure (1569) de Soto admits that he has heard of the many illicit methods of tricking “Ethiopians” into captivity. “If this is true,” de Soto writes, “neither those who take them nor those who buy them, nor those who own them can have a clear conscience until they set them free…”

Tomás de Mercado (c.1500-1575) questioned the participation of Spain and Portugal in the slave trade though he also accepted the just cause argument for enslavement. In Summa de tratos y contratos (1571) written as a moral and legal guide for merchants, de Mercado states that since the King of Portugal has “dominion and lordship,” then it must be presupposed that he acts with reason and justice. Questioning his authority would be to “enter into a labyrinth.” De Mercado prefers to accept that the Christian tradition recognizes several “causes by which one can be justly captured and sold”: as a loser in a just war, when a crime carries the penalty of enslavement, and when out of poverty or extreme indebtedness an adult (or his creditors) sells himself or his children into slavery. On the one hand, de Mercado considers that these causes were more often accepted by people in Guinea (Africa) because “they are vicious and barbarous” and “… there is no supreme ruler to whom all owe obedience and respect.” On the other, he notes that “the Portuguese and Castilians…in giving it the entitlement of a just war…necessarily mix together…a majority that are unjust…as [they]…go hunting as if they were stalking deer…In this way an infinite number of captives [are taken] against all justice.” Slave traders increased their burden of sin by letting hundreds of Africans die in captivity during the transatlantic crossing or by not offering them any opportunities to be rescued once they arrived in the Caribbean. At least in their land, says Mercado, “although unjustly enslaved … they would have hope of the better remedy of being freed.” Therefore, de Mercado warns that the only way Spanish merchants could avoid sinning would be to avoid trading in slaves. “It is well-known that in taking the Negroes from their land to the Indies or to [Spain], two thousand lies, one thousand thefts … and one thousand abuses are committed.” De Mercado underscores that it was no use for Spanish merchants to try to obtain moral and legal absolution by writing to Lisbon. Visibly annoyed he warns them: “Do you think that we have here another law or a different theology? What is said there [in Lisbon], we say, and it seems to us even worse, as we have more information on the evil that is occurring.” De Mercado’s statement confirms that from very early on, the Atlantic slave trade generated moral and legal debates both in Spain and in Portugal.

In 1555, the Dominican Fernão de Oliveira (c.1507-1585), published Arte de guerra no mar, one of the first Portuguese texts denouncing Christians as inventors of “such an evil trade, never used nor heard of before among brothers.” He argues that wars were being propagated in Africa with the sole aim of justifying the capture of Negroes to enslave them. “To me it seems that their enslavement is very imprudent…because they do us no harm, nor do they owe us anything, nor do we have a just cause for making war on them.”

Some years later, the 16th-century Spanish Dominican priest Bartolomé Frías de Albornoz, the University of Mexico’s first professor of civil law, wrote in Arte de los Contratos, “[certain] sales not prohibited by law are …dangerous to the conscience… such as the contracts referring to [the sale of] Negroes.” Like de Mercado, De Albornoz reasons that if the King of Portugal sanctioned the slave trade, and if priests bought and sold Africans, then it must be presumed that a justification exists. Nevertheless, he seems unsure that the causes widely understood to be legitimate are truly just: “…whoever wishes to see some causes that justify servitude can peruse the ones outlined by de Mercado in his Treatise, though he does not seem to show much satisfaction in them; and I am even less satisfied with the ones he considers just than those he admits are not…” De Albornoz further questions the legitimate causes arguing that “not even Jesus Christ” could justify the enslavement of a human being because all men must be presumed free, and natural law favors the weak, contradicting any justification for the enslavement of women and children or those sold owing to hunger. He adds that to convert Africans to Christianity cannot be a just cause because Jesus would not have preached that to obtain “freedom of spirit it is necessary to pay with bodily bondage.” Therefore, de Albornoz recommends that merchants not continue to invest in such a “bloodthirsty” trade.

Over the period 1594 to 1614, the Jesuit Luis de Molina (1535-1600) published De iustitia et iure in which he uses Aristotle’s premises to argue that slavery is morally acceptable under limited conditions but he employs a historical method to discuss slavery in the American context. De Molina does not venture to pass final judgment on the subject of the legality of the Portuguese slave trade as he believes it was a question that should be resolved by renowned theologians. Nonetheless, de Molina claims to have undertaken extensive research on the slave trade through his conversations with Portuguese slave traders. He concludes that sufficiently strong arguments existed for condemning the trade of Africans as “impious and unjust,” thus those who engaged in it “sin gravely and run the risk of being condemned for eternity.” Since de Molina considers the only benefit of slavery to be the conversion of infidels, he proposes that missionaries first prohibit the slave trade and then go directly to Africa to Christianize. In the end, de Molina exonerates those who bought slaves in good faith.

Other religious men preferred to direct attention to the excessive abuse and mistreatment of slaves. The Jesuits in Brazil—such as Antonio Vieira (1608-1697)—continued with this line of criticism throughout the seventeenth century. Vieira fought the enslavement of indigenous people but accepted that of Africans as an inevitable reality and a necessary economic activity. In his sermons he preached the slaves’ equal humanity, reprimanded the owners for mistreatment and asked that their evangelization be guaranteed. However, he urged blacks to resign themselves to slavery because it was the road to their salvation. Historian Ronaldo Vainfas asserts that the Jesuit’s concern in Brazil began with the slave market boom and the growth of the Palmares runaway slave community. Until then, Jesuits opposed the captivity of indigenous people without exhibiting any indignation over the unjust detention or cruel punishment of African slaves. Vainfas emphasizes that their concern was masked in the project of Christian-slavery because the conversion to Christianity was incompatible with freedom for slaves.

Further north, in Cartagena de Indias, Sevillian Jesuit Alonso de Sandoval (1576-1652)published a treatise in 1627, in which he carries out a detailed ethnological study of Africans in captivity. Though Sandoval condemns the mistreatment of slaves and argues that they are human beings equal before God, his purpose was not abolitionist. His mission was to evangelize and to console suffering slaves, work for which his assistant Pedro Claver (1580-1654) was canonized two centuries later. Like Vieira in Brazil and followers of de Molina, Sandoval and Claver did not agonize over the (un)just cause of captivity. They preferred to accept the legitimacy of slavery as a valid way of bringing Christianity to infidels.

In sum, none of the above religious men denounced the practice for its inherent immorality or called for an end to the slave trade. For this reason, it is extraordinary to find two Capuchin missionaries, Francisco José de Jaca de Aragón (c.1645?-1688) and Epifanio de Moirans de Borgoña (c.1644-1689), who clearly condemned the slave trade as violating all moral, religious and legal arguments. De Jaca and de Moirans preached that slaves were free by nature, called for the abolishment of slavery, and demanded ample economic compensation for all victims. As a result, several slave owners accused them of being seditious missionaries. The documents that give testimony to the Capuchins’ story are the result of a trial that began in Havana in 1681 and finished in Madrid in 1686. The texts remained forgotten for 300 years until José Tomás López García published them in 1982 in a book entitled Dos defensores de los esclavos negros en el siglo XVII.

During their lengthy captivity, de Jaca and de Moirans wrote in their defense that the institution of slavery violates natural law, divine law and the law of nations. By making reference to biblical texts and religious authorities, they carefully refute the arguments that justified slavery and conclude that it was a “manifest robbery of the negroes’ freedom.” Basing their argument on Saint Thomas’ doctrine of restitution, de Jaca and de Moirans demanded compensation as the only way of redeeming—in part—the “terrible sins” committed by all who had participated in the slave trade. De Jaca wrote “these negroes, and their ancestors, are free, not only as Christians, but also in their native land. And as such,…the obligation exists to restore their freedom, but also, in pursuit of justice, to pay them what they would have inherited…, what would have enriched them, the lost time, the labor and the damages that they have suffered… for their enslavement and personal service…”.

De Moirans more fully develops his own arguments: “Slavery being unjust, the sale and purchase unjust, possession iniquitous and being… in bad faith against natural, divine, positive law and the law of nations, it is obvious that their freedom must be restituted and all that which derives from slavery; as well as all that the owners have gained. … Because, in truth, with the blood, sweat and labor of the unjustly enslaved slaves…enrichment has taken place through injury and injustice in the Indies.”

De Moirans explains that restitution derives from something unjustly received or unjustly held, which meant that there is an extended responsibility to any who participated who benefited or did not prevent the slave trade, including all slave-using societies: “… the kings, the Spanish merchants, Portuguese society, the Paris dealers, those who buy blacks and sell them to others, the transporters, the ship owners and the others who are effectively involved in this… in the Indies and in Europe… are obligated to restitute the freedom of the blacks, as well as the damages incurred and the value of their labor.” Both were aware that the damages were so extensive that restitution would be impossible. “The [victims] are not few, furthermore, there are so many blacks who over time have been exported to the Indies, that neither the Indies, nor Spain, would have enough for the restitution of their labor, its fruits and the damages that resulted, or for the liberty unjustly usurped.” De Moirans thus offers a solution in accordance with Saint Thomas doctrine: when the victim is known, his heirs and descendents should be compensated, but if he is not alive or his family is unknown, then all the owner’s money and ill-gotten benefits should be given to the poor, “because these are the fruits of iniquity and … they are obliged to do so under threat of eternal condemnation.”

Most significantly, de Moirans and de Jaca concluded that the tragedy of slavery was not based on an erroneous theological interpretation, nor on the innocent acceptance of a just cause, but rather on the intentional deafness and blindness of all of those who participated in some aspect of the trade, be they as vendors or recipients of slaves. The two Capuchins repeatedly noted that there were enough legitimate arguments against the trade in human beings for all to have rejected it. Aristotle’s just cause theory—it was widely known—did not apply to the case of the enslaved Africans brought to the Indies. The only possible conclusion was that the participants in the slave trade were acting in bad faith or, at a minimum, that so much injustice had blinded those who could otherwise have denounced and impeded it. De Jaca affirms “If the professors, theologians, confessors, religious men had not been silent dogs in the Indies, then iniquity and injustice would not have developed so enormously and without remedy.”

Although de Jaca and de Moirans’ daring was truly extraordinary, their texts update a series of suppositions already implicitly or explicitly formulated in previous work. It is therefore worthwhile to ask why this series of critiques did not prosper and how the 16th- and 17th-century debate on slavery came to be forgotten. We cannot simply suppose that these voices were too marginal, given that their texts circulated widely as later readers, such as de Jaca and de Moirans, demonstrated. Also, during the 17th century the Capuchins, Jesuits, and Dominicans continued protesting some aspect of the slave trade to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in Rome, thus confirming that there was enough debate to consolidate a solid intellectual opposition to slavery.

This context predates modern liberal concepts of human rights. Yet, it underscores how well-intended legal arguments or actions may actually support the status quo while disregarding those dissonant voices that could be shedding light on the core of the problem The emphasis on the need to have a just cause for enslavement or the band-aid of tending to the suffering of slaves only resulted in drawing attention away from the real problem: the enslavement of human beings supported by the economic interests of a colonial system.

In light of Kennedy’s nagging questions, we might re-consider how the sometimes confining language of human rights may not be sufficient to address situations which call for a deeper understanding of local realities and for more radical emancipatory ideas to flourish. Such a reassessment of the human rights discourse may be more effective in influencing the broader public (including students) by linking ideas of human dignity to the actual struggles that local communities have faced.

Fall 2003, Volume III, Number 1

Liliana Obregón holds a doctoral (S.J.D.) degree from Harvard Law School and is currently an assistant professor of law at the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia. She previously worked for the Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL) in Washington D.C. and was a fellow at Harvard’s Law School’s Human Rights Program during 1996-1997. Some of the research used here is based on an article written by the author for Beyond Law – Race, Racism and Law in the Global South, ILSA, March, 2002.

Related Articles

Human Rights and Reconciliation

I feel the strongest of bonds with Cuba. I was born there and left as an 11-year old with my family for the United States shortly after the revolution came to power. We thought our stay here would…

A Violence Called Democracy

It became known as Guatemala’s Black Thursday. Peasant demonstrators swept through the streets of Guatemala City. They smashed windows and burn cars, while some chanted “We want…

My World Is Not of This Kingdom

Gregory Rabassa translated My World Is Not of This Kingdom by João de Melo because it was the most astonishing novel he had read since One Hundred Years of Solitude. He undertook this…