Reverse Urbanism

Lima: A Topsy-Turvy City

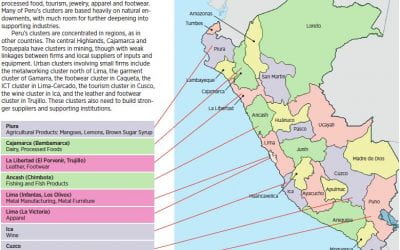

Before and after comparison of Ciudad de Dios, south of Lima, 55 years later (1955-2010). Image source: Servicio Aerofotográfico Nacional and Google Earth.

In 1973, eleven-year-old Rita arrived to Lima from Caraz, a town high in the Andes. Her mother used to work at my grandparents’ house in Caraz but sent Rita to stay with my family in Lima. Rita lived in our house for almost 20 years. She raised my brothers and me while finishing high school and then studying at the university. In 1991, she married her boyfriend Rogelio and they both started to look for somewhere to live.

Given the humble economic conditions in which they started their married life, they could not afford traditional housing options. Instead, they decided to follow a common practice in Lima for those of similar socioeconomic conditions: to informally occupy lands in a barriada (shanty town). It was actually my mom’s idea, after she heard some rumors at her job at the Ministry of Education about some colleagues occupying agricultural lands in the north of Lima. In April 1991, Rogelio and Rita joined around 2,000 other families and settled in the arid periphery of Lima, hoping that the land they were sleeping on that night would become theirs in the future.

Police came into the barriada. Authorities tried to evict the settlers. But after a series of fights, they managed to remain. Rita and Rogelio knew that the police had only a small window of time to forcefully evict them, and after that interval they could only be evicted by judicial and legal means. Furthermore, they knew that the government almost always ended up granting amnesty, legalizing the settlement and granting land titles. At the beginning, the informal settlers managed and organized everything by themselves. They laid out and built the streets and walkways, and obtained water, electricity, security and garbage removal.

Twenty-three years later, that place of sand and dust is now a vibrant sector of Lima, full of small local businesses and services such as banks, universities and malls. Rita and Rogelio live in the third house they have built. Their house is no longer the first reed hut they built to occupy the land, nor is it the second temporary adobe construction they built when the exact location of their plot was fixed. This third house is a two-story brick building that they built themselves with the aid of their neighbors. Rita and Rogelio have not only managed to build a house for their family, but they have also helped shape a vibrant community for themselves and their neighbors.

Like Rita, millions of people migrated to Lima during the second half of the 20th century. They all came for their own reasons, but they shared the quest for better opportunities for themselves and their families. They are the founders of the shape of contemporary Lima, a massive example of reverse urbanism that started with informal settlements and evolved into the construction of more structured settlements that enabled a better quality of life for its residents. Urbanism usually starts the other way, constructing the infrastructure and the streets first, and occupying them afterwards.

In part due to this topsy-turvy process of reverse urbanism, Lima with its nine million inhabitants has become the second largest desert city in the world. As the result of fifty years of intense internal migration and a population increase of almost 500 percent since 1950, Lima is the biggest city in Peru, holding one-third of the country’s population. It is also the largest coastal, Andean and Amazonian city in terms of population concentration. Lima is metaphorically the new genetic code for Peru, as it is a multicultural city where 87.3 percent of its population has immigrant roots—domestic and international.

It is the history of how Lima, a city in which 62 percent of its population lives in originally informal areas around the periphery, became the city that is today reflected in its inhabitants’ economic progress and its socio-cultural background. Moreover, it is also important to understand contemporary Lima in relation to its general history. Architects and urbanists are fond of saying that there were several Limas within Lima’s current footprint.

Traditional Lima

Lima, founded as the capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru on January 18th of 1535, was a city mainly designed for Spaniards. Indigenous people were excluded from the city itself, and forced to live outside the city, in reductos (indigenous towns). Traditional Lima was composed of rational square urban grids and Spanish-style colonial houses. It was a small city that maintained commercial and trade networks with nearby towns such as Magdalena, Chorillos and the port of Callao. The grid, size, layout and footprint of the city remained relatively unchanged until years after Peru’s independence in 1821, mainly because of the existence of the city wall. This wall, built in 1684 to protect the city from pirates, was torn down 185 years later in 1869.

The marginalization and exclusion of native Peruvians from traditional Lima and other important coastal cities persisted even after Peru’s independence, mainly because of the nature of the Independence War, which mainly pitted the Spanish against the Criollos (the Peruvian-born descendants of Spaniards). This conflict mostly excluded the native Peruvians, who continued to be marginalized.

In his new book Perú: Estado desbordado y sociedad nacional emergente, the well-known anthropologist José Matos Mar addresses the coexistence of two Perus: the official Peru, made up by the relatively wealthy traditional families, with Spanish or foreign roots, living primarily in Lima and coastal cities; and the other Peru, whose uneducated and poor indigenous Andean and Amazonian families were outsiders to any kind of nationally inclusive vision.

Modern Lima

At the beginning of the 20th century, traditional Lima started to look ahead and to think big in terms of urban planning and expansion. Lima and Peru in general were facing two milestone occasions: the reconstruction period after the 1879-1883 Peruvian-Chilean war and the preparation for the celebration of the first 100 years of independence.

Modern Lima emerged around the 1920s with the construction of some large parks and wide avenues, borrowing such Anglo-Saxon urban ideals as the Garden City. Then, in 1948, Lima started its first Pilot Plan, heavily influenced by Josep Lluis Sert, urban designer and later dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, during his visits that year to the country.

Modern Lima began trying to do the right thing with important housing, parks and transportation projects such as the Unidad Vecinal #3, Parque de la Exposición or Arequipa Avenue. Nonetheless, modern Lima ended up absolutely overwhelmed by the complexity of the reality of the heavy influx of people from the countryside, beginning in the 1940s but really bursting in the 1960s.

Modern urban planning was a matter of buildings and roads, largely conceived in terms of infrastructure. Little thought was given about how to manage the political, social, economic, legal and sanitary complexity of millions of people spontaneously inhabiting and urbanizing Lima. However, in an effort to deal with sanitary conditions and violence, the government started to legalize some of these informal settlements. This reaction can be conceived as the beginning of contemporary Lima and the end of what could have been modern Lima.

Contemporary Lima

The second half of the 20th century shows the real history of today’s contemporary Lima, as well as providing a perfect example of reverse urbanism, since barriadas in Lima started in reverse: the land was first occupied and settled, and then public services, utilities and facilities for living were obtained through collective work, participation of the community, as well as negotiation with the government. The story of how contemporary Lima became the city it is today can be summarized in three moments:

The first moment is one of growth and expansion, marked by early mass migrations from the provinces and rural areas to Lima during the 1940s. People came because of “pull” factors such as better opportunities, education and jobs and because of “push” factors such as loss of land, economic crisis and natural disasters. Starting in the 1970s, this migration increased dramatically, triggered by events such as the Agrarian Reform and the subsequent breakdown of important rural economies, and the presence of the terrorist group Shining Path in rural areas.

The decades from the 1940s to the 1990s have been described by anthropologist Matos Mar as the years of desborde popular (popular overflow), represented by the mass migration of the people of the “other Peru” towards the city that until then had belonged to the people of the “official Peru.” The millions of people who arrived to Lima during these years created barriadas such as Villa el Salvador, Ciudad de Dios and Ventanilla on the periphery of the traditional city, a process which continued until the 1990s.

Development

Throughout the 1990s, under the Alberto Fujimori presidency, drastic public reforms stabilized and liberalized the economy. Several public services were privatized. Generalized lack of public control and regulation enabled the growth of an informal parallel economy totally overlooked by the traditional society. Informal markets, grocery stores, transportation companies, food trading, clothes manufacturing and other services boomed alongside the privatized economy.

The government also adopted radical policies for dealing with the barriadas issue in Lima. During the early 1990s, more than a million families informally occupying state lands were granted land tenure and titles. This policy stemmed from the hope that families with legal ownership would start investing more money in their own houses and neighborhoods. In other words, along with the reforms that brought prosperity and money to the population, both formally and informally, the idea was also to create a platform that enabled citizens to self-invest in the city and therefore to “build city.”

These reforms, which stimulated the immigrants’ already strong sense of organization and community work, transformed the neighborhoods of Lima’s periphery. Their originally flimsy appearance evolved into a more robust brick-residential urbanization filled with small local businesses. Nonetheless, major private services such as banks, schools, universities, clinics and shopping centers were still not interested in investing in these areas of the city, considering them too risky in terms of profitability.

Consolidation

As a consequence of the political reforms started in the 1990s and the strategic macroeconomic decisions of the early 2000s, Peru’s macroeconomic performance started to improve noticeably in relation to the Latin America region from 2005 on. Financial stability, low inflation rates and private and state investment contributed to create an environment of sustained economic progress easily noticed by the population. Between 2005 and 2011, the average GDP per capita increased annually by 7.9 percent, giving birth to the so-called emergent middle class, those with immigrant roots.

These emergent middle class families represent more than a quarter (28 percent) of the total urban population of Peru today, accounting for nearly 40 percent of the country’s total income. Their strong economic presence is no longer overlooked by private and formal enterprises which have now radically transformed their business strategies and are finally investing in the “emergent districts” of Lima.

Today’s contemporary Lima is finally entering into a process of consolidation that has brought more equality to its citizens. It is perceived as an optimistic city that is slowly acquiring its own flavor and identity. In the words of Matos Mar, today’s Lima is finally a better representation of Peru, its mestizaje (racial mixing) and cultural diversity.

Contemporary Lima has shown how reverse urbanism became a way of making city, bringing prosperity to citizens at moments when the official plans lost direction and were totally overwhelmed by reality. Nonetheless, reverse urbanism was a painful way of making city. It was done at a cost of thousands of hours of hard work of its citizens in a context of huge inequality, segregation and fragmentation. Contemporary Lima was developed throughout the accumulation of small neighborhood patches that collectively became a fragmented city that today struggles to find its identity.

Much work is still needed to articulate policies and services that guarantee justice, equity and accessibility for all residents of Lima. However, in a world in which close to one billion people live in slums—the rapidly urbanizing product of rural-urban migration—Lima’s fifty years of intense reverse urbanism offer invaluable lessons that the rest of the world could use in other contexts.

Related Articles

Towards a National Value Proposition

Peru has been one of the most remarkable economic growth stories of the last decade, both compared to its own historic record and to its peers in Latin America and beyond. A combination of sound macroeconomic policies since the mid-1990s and a benevolent international economic environment with growing demand for Peru’s natural resources has allowed the country to prosper.

A Taste of Lima

Each one of us has a grandmother or mother, grandfather or father whose dish—humble or elaborate—transports us back in time or space, surrounds us with people, places, images, languages, and even fragrances of the past. The dish—or the memory of the dish—evokes a smile, or perhaps a tear, and generally seems inimitable by those who share the memory.

Seeking Progress in Twentieth-Century Peru

The year was 1993. My wife Barbara and I had just arrived in Lima, with the intention of working there for two or three years. I had a job in a USAID project, while my wife was part of a World Bank planning group in the Ministry of Education. Peru was just recovering from staggering blows, both economic and political.