Review of Connecting Lines: New Poetry from Mexico

Connecting Lines: New Poetry from Mexico Luis Cortez Bargalla, editor, Forrest Gander, translation editor Louisville, KY: Sarabande Press

Líneas Connectadas: Nueva Poesía de los Estados Unidos

April Linder, editor

Louisville, KY: Sarabande Press

Lou Dobbs and other talk show hosts want us to believe that a so-called Mexican invasion is denying “true” Americans their jobs, democracy and destiny. Few among them comment on a peaceful, more subtle Mexican “invasion” that will help us see why fears of blending Mexican and U.S. culture are misplaced. One by one, since the turn of the century, anthologies of a Mexican poetry trumpeting innovation and diversity have been sneaking into the country. Watch out! If you read one you will realize that Mexico is a rich and complex country and its culture will only enrich you and yours.

Before 2002, the most recent comprehensive Mexican poetry anthology in English had been published in 1970. Since then there have been three, and Connecting Lines is the broadest sample of Mexican poetry to date. That 1970 anthology, New Poetry from Mexico, was a masterpiece that whispered through U.S. poetry louder than whisper campaigns on talk radio today about migrants stealing our jobs. New Poetry from Mexico, edited by the U.S. poet Mark Strand, was an abridged version of the landmark Poesía de Movimiento (1966), edited by literary luminaries Octavio Paz, Ali Chumacero, Jose Emilio Pacheco and Homero Aridjis. These books collected and canonized Mexican poetry’s turn to modernism and opened the door to their international acclaim.

In his introduction, Paz argues that Mexican poetry is one of a broader history:

The poetry of Mexicans is part of a larger tradition: that of the poetry of the Spanish language written in Spanish America in the modern epoch. This tradition is not the same as that of Spain. Our tradition is also and above all a polemical style, at war constantly with the Spanish tradition and with itself: Spanish purism against cosmopolitanism; its own cosmopolitanism against a will to be American. As soon as this desire for style asserted itself, to part with “modernism,” it set up a dialogue between Spain and Spanish America.

Why then did it take until 2002 to get another dose of contemporary Mexican poetry? Part of the reason is that poetry in the United States took a provincial turn for a spell. Another reason is that the immense popularity of Paz among poetry readers here took up the “room” for a Mexican poet. After all, if you were versed in world poetry in the 1980s and 1990s you had to be reading Joseph Brodsky (Russia), Zbigniew Herbert (Poland), Bei Dao (China), Ernesto Cardenal and Daisy Zamora (Nicaragua), Kamau Brathwaite (Barbados), Denis Brutus (South Africa) and Seamus Heaney (Ireland) to be able to hold your own.

Paz passed away in 1998 and will go down in history as one of the 20th Century’s greatest modern poets. Ironically, his death has opened a window to a new generation of Mexican poets. Shortly after his death Copper Canyon Press published Reversible Monuments: Contemporary Mexican Poetry, edited by Monica de la Torre and Michael Wiegers. The volume is the broadest yet in scope and gives the deepest treatment of poets born after World War II. The book features 31 male and female (women were excluded from New Poetry of Mexico number) poets over a (bilingual) span of 675 pages. What’s more, one can find translations of indigenous Mexicans as well. Natalia Toledo, for instance, is from Oaxaca and writes in Zapotec.

Connecting Lines provides much broader coverage than Reversible Monuments, including more than fifty poets from a variety of threads in Mexican poetry. It is the place to start for Mexican poetry in English, while individual poets may be covered in more depth in Reversible Monuments. (Some, such as Pura Lopez-Colome and Coral Bracho, now have book-length collections in English.)

Kenneth Rexroth, one of the best translators of his time, said of the process of translation, “The first question must be: is this as much of Homer, or whomever, as can be conveyed on these terms to an audience? Second, of course, is it good in itself?” In other words, the second test is that the work in English has to rank among solid poetry by U.S. poets.

In many ways the recent wave of anthologies is cursed by the first. New Poetry of Mexico had some of the best poets of the time as translators, W.S. Merwin, Philip Levine, Mark Strand, and Donald Justice. Yet the new poetry anthologies, and Connecting Lines in particular, also include some greats. Carolyn Forche and Forrest Gander (former Briggs-Copeland Poet at Harvard) are the most accomplished and best known. Translations by Monica de la Torre and Jen Hofer (poet and editor of a 2003 anthology by University of Pittsburgh Press titled Sin Puertas Visibles: An Anthology of Contemporary Poetry by Mexican Women) and Don Share (poetry editor of Harvard Review) stand out as well. Others are more uneven.

It is hard to characterize the poets in Connecting Lines or Mexican poetry in general. Like poetry in the United States, Mexican poetry has splintered into political, formal, personal and historical in rich ways. However, it is striking—in stark contrast with U.S. poetry—that the vast majority of the poets are translators themselves. Quite a few U.S. poets do not read foreign languages well enough to translate them, leading them to an insular set of (worked over but endlessly rich) influences in the English tradition. Mexicans are much more internationalist and thus can draw on more history and style for innovation and perception in language.

Francisco Segovia is one such poet. He works as a researcher at El Colegio de Mexico putting together a “Mexican Dictionary” and treats Mexican Spanish very much as William Carlos Williams treated American English as its own language. Like Williams, Segovia’s poetry is imbued with knowledge of the great metaphors of Spanish and Asian literature and the particulars of Mexican reality—Pemex and the city together in a poem translated by Harvard’s Don Share with César Pérez:

Pigeons eat bread on the

sidewalk,

blindly hammer crumbs

on the hard street,

nail their beaks to the cement, poke

the ground

like flocks of derricks

in the oil fields.

This Mexican poetry “invasion” is comparable to the British invasion of rock and roll over thirty years ago. British musicians “discovered” African-American blues, absorbed it, and breathed a different life into it that was then rediscovered such that it “took over” the U.S. music scene. Mexican poetry has also absorbed the best of U.S. and world poetry and is now coming back into the country with a set of gifts from the deepest core of Mexico to the far out reaches of the world. It will be a treat to those who read Spanish or English and some of its certainly more fun than The Hollies!

A final note on the companion volume, Líneas Conectadas: Nueva Poesia de los Estados Unidos. The publisher decided on a two-volume bilingual set: one of Mexican poets for a U.S. audience, one of U.S. poets for Mexico. Interestingly, there is actually no other anthology of U.S. poetry like Líneas Conectadas. Most anthologies of poetry in this country are from a particular “school” that is trying to distinguish itself. This volume is an amazing representation of the breadth of poetry in the United States today. Followers of U.S. poetry will be refreshingly surprised to find Sherman Alexie and Gjertrud Schnackenberg in the same book. Thus, it does great service to the craft for Mexicans, but also readers of English who don’t read poetry much might start there for poetry in their own language.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Dance!

We were little black cats with white whiskers and long tails. One musical number from my one and only dance performance—in the fifth grade—has always stuck in my head. It was called “Hernando’s Hideaway,” a rhythm I was told was a tango from a faraway place called Argentina.

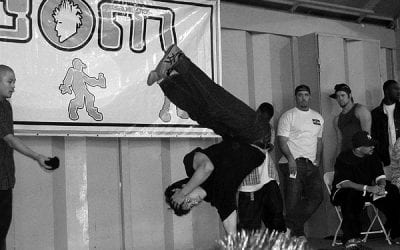

Brazilian Breakdancing

When you think about breakdancing, images of kids popping, locking, and wind-milling, hand- standing, shoulder-rolling, and hand-jumping, might come to mind. And those kids might be city kids dancing in vacant lots and playgrounds. Now, New England kids of all classes and cultures are getting a chance to practice break-dancing in their school gyms and then go learn about it in a teaching unit designed by Veronica …

Dance Revolution: Creating Global Citizens in the Favelas of Rio

Yolanda Demétrio stares out the window of our public bus in Rio de Janeiro, on our way to visit her dance colleagues at Rio’s avant-garde cultural center, Fundição Progresso. Yolanda is a 37-year-old dance teacher, homeowner, social entrepreneur and former favela (Brazilian urban shantytown) resident. She is the founder and director of Espaço Aberto (Open Space), an organization through which Yolanda has nearly …