Roald Dahl, the Caribbean, and a Warning from His Chocolate Factory

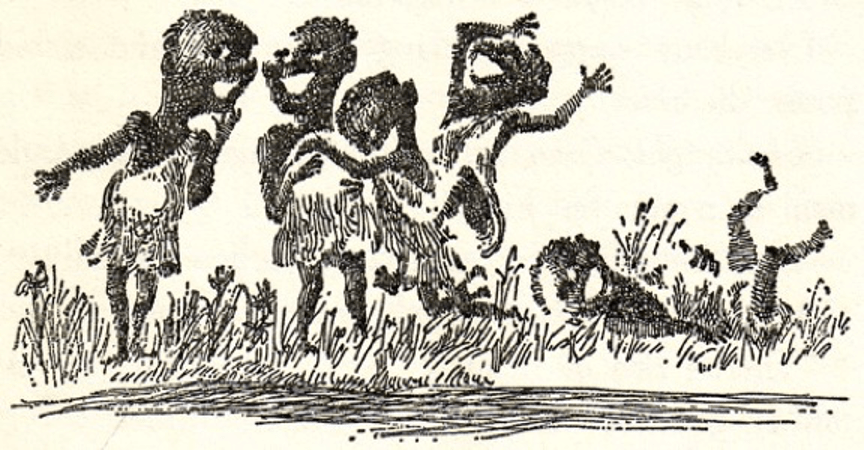

Oompa-Loompa illustration by Joseph Schindelman, copyright © 1964 and renewed 1992 by Joseph Schindelman, from CHARLIE AND THE CHOCOLATE FACTORY by Roald Dahl. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

People in the United States love chocolate, but history—not so much. For generations, we manufactured blatantly racist textbooks that taught young readers about the inferiority of African Americans. Since the 1980s, if not earlier, public schools began dropping history from their curriculums or assigned athletic coaches the task of teaching such classes. But history is far from a dead thing. “We carry it within us,” African American novelist James Baldwin memorably remarked in his essay, “The White Man’s Guilt.” We “are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do. It could scarcely be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations.”

Chocolate also has a history and, despite its sweetness to many Americans, it has a bitter legacy. Like sugar, it became the business of colonial—and slave trade—powers, and Great Britain, since the mid-17th century, sought to be in the thick of it. As British literature professor Kate Loveman wrote in Journal of Social History in 2013, the Earl of Sandwich tried to entice the English government into cultivating new harvests, including cacao, in the West Indies, and especially Jamaica. While initial English efforts to produce Jamaican cacao—highly prized today—proved successful, exporting “quite large quantities,” as one imperial historian wrote, the crop soon fell victim to hurricanes and disease and competition from sugar as the more profitable (slave-produced) investment.

The very idea of chocolate is inextricably linked to slavery. Indeed, as early as the 1850s, U.S. abolitionists had protested the cocoa trade, and the cotton trade, pledging themselves to buy only free-labor products. In this way, the antislavery newspaper the National Era wrote in 1856, “the sweet may be obtained without the bitter.”

The first cocoa shipments to Europe began in 1585 and ever since the commodity has been identified with the colonial world of Central America and the Caribbean, but especially with West Africa. World’s cocoa production shifted to West Africa (about 70% today), specifically because of Britain’s interests there, especially Cadbury, the famed British chocolatier. Yet, as Jill Lane wrote in her 2007 essay “Becoming Chocolate, A Tale of Racial Translation,” the industry there offers an important warning for Caribbean nations. African cocoa production remains “fraught with social problems, including child and slave labor. . . .” Today, millions of West African children, especially in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire, are caught up in the cocoa trade. Many survive “on little food, little or no pay, and endure regular beatings.” By one estimate, roughly half of the world’s chocolate comes from the labor of exploited children.

As Daphne Ewing-Chow of Forbes magazine pointed out in 2019, Trinidad and Tobago are experiencing a steady increase in cocoa production after a century of progressive decline—from 30,000 tons per year to less than 500 tons. Cocoa orchards have been revived in Jamaica and thousands of farmers have become involved in production. Moreover, women in St. Lucia are increasingly becoming involved in cocoa production and have formed a network of rural female producers. Is this new Caribbean production free of the exploitation still found in Africa? What does cocoa production mean for today’s world? Do producers understand the contexts of their business?

Roald Dahl, one of the world’s most successful writers of children’s books, grew up with chocolate—and white supremacy—in his veins. Born of Norwegian parents in Wales, a World War II fighter pilot, and British intelligence officer, Dahl became part of the lives of millions of children around the world, especially through two of his works, James and the Giant Peach (1961) and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964). His fame only increased when he married the U.S. actress Patricia Neal.

His adult career began in 1938 with the Asiatic Petroleum Company, soon to become a part of Royal Dutch Shell, in the former German East Africa, then known as Tanganyika. His adventure—and his later career as a writer—were nourished by the imperialism and racism he had grown up with. While in prep school, Dahl dreamed about the gold and adventurous life that might await him in Africa, where he remarked, “there is a great advantage in traveling to hot countries where niggers dwell.”

Moreover, his prep school resided very near the Cadbury plant. He and other students served as test subjects, passing judgment on various chocolate products—and giving him a life-long addiction to the candy and additional inspiration for his famous book. Thus, when he began his literary career after the war, one of the first stories he wrote—employing typical “colored” dialect—revolved around a sleazy and dangerous, brown-skinned Jamaican gambler who owned a Cadillac.

Magical, marvelous and imaginative is how virtually everyone understood Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, a story about a poor child, Charlie Bucket, who by chance received a golden ticket to a glowing future. No one can deny the genius of the book or its author. Looking at the whole of his children’s writings, one analyst even saw in them Dahl’s quest for a father, whom he lost as a child, a man who “made a world that was fair and wonderful.” What reviewers and readers around the world did not see, however, was how slavery underpinned his writing and how white supremacy fortified it. The power of a positive imagination, and what (white) readers desired to see, simply overwhelmed the obvious.

The depiction of the Oompa-Loompas in Charlie and Chocolate Factory is so brazen that Dahl might have had a copy of Thomas Clarkson’s 1829 description of slavery in the British West Indies by his side when he crafted the book. When Charlie, the four other golden ticket holders, and their parents first spied the Oompa-Loompas they cried out: “What are they doing? Where do they come from? Who are they? “Aren’t they fantastic! No higher than my knee! Their skin is almost black!”

Willy Wonka tamped down speculation that he made them of chocolate. “They are real people! They are some of my workers!” He advised the group that these tiny black people had been “Imported direct from Africa!” They belonged to “a tribe of tiny miniature pygmies known as Oompa-Loompas. I discovered them myself. I brought them over from Africa myself—the whole tribe of them, three thousand in all. I found them in the very deepest and darkest part of the African jungle where no white man had ever been before.”

Wonka explained that the tribe had been starving, subsisting on green caterpillars, but longing for cacao beans, “oh how they craved them.” He bargained with the tribe and promised that if they agreed to “live in my factory” they could have all the cacao beans they wanted: “I’ll even pay your wages in cacao beans if you wish!” So, the black pygmies traded their freedom for permanent enslavement and all the cacao beans they could eat. After the tribal leader agreed to stop eating green caterpillars and work for “beans,” Wonka “shipped them over here, every man, woman, and child in the Oompa-Loompa tribe. It was easy. I smuggled them over in large packing cases with holes in them, and they all got here safely.” As Britain had outlawed the slave trade in 1807, Wonka had to smuggle them to England in packing cases, in conditions that sounded almost as horrific as the Middle Passage.

Dahl’s descriptions clearly exploited the demeaning ways whites conceived of the slave experience and treated the Oompa-Loompas as things to own. One of the lucky white children who gained admission to the factory, Veruca Salt, the girl who got everything she wanted, wanted an Oompa-Loompa. “I want an Oompa-Loompa right away!” Ok, her exasperated father said. “I’ll see you have one before the day is out.”

Willy Wonka embraced the role of master. If he clicked his fingers three times an Oompa-Loompa would appear and quiver at his loin. He “bowed and smiled, showing beautiful white teeth. His skin was almost pure black, and the top of his fuzzy head came just above the height of Mr. Wonka’s knee. He wore the usual deerskin slung over his shoulder.” A slave galley even made an appearance in the book, one powered by pygmies who rowed on a river of chocolate. Just to further highlight the slave analogy, Dahl deviously introduced whips, “WHIPS—ALL SHAPES AND SIZES.” And why whips? Well, “For whipping cream, of course!” Riveting the idea that these black pygmies were Wonka’s property, to which he could do whatever he wanted, he subjected Oompa-Loompas to hair-growing medical experiments and product testing that turned some into blueberries.

Eleven years after he had written Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Dahl confessed to being “mildly ashamed” about his attitude toward those Africans that had worked with him in Tanganyika. His imperial adventure, he confessed, seemed “not right.” He admitted that he had unconsciously fallen into an imperial frame of mind, something that could not be helped: “You can’t buck the tide,” he remarked. “It was the last days of the British Empire.”

Yet, at almost the exact same time, he became outraged when anyone found racial prejudice in the wonderful fantasy tale that he had crafted and dedicated to his brain-damaged son. “It didn’t occur to me that my depiction of the Oompa-Loompas was racist,” he remarked when the new edition of the book emerged in 1973, “but it did occur to the NAACP and others . . . which is why I revised the book.” Dahl hated criticism, especially when it pointed to his deepest flaws. His bewilderment, if any, came not from embarrassment or regret, but from the fact that his racism had been exposed to public view, threatening his reputation and, perhaps, his profits.

Dahl learned nothing from the controversy. When finishing another successful children’s book, The BFG, his first draft of the friendly giant at the center of that book emerged as the very worst imitation of a Zip Coon figure, a black, flat-nosed, giant with “thick rubbery lips . . . like two gigantic purple frankfurters lying on top of the other.” For once, an editor spoke up and his new publisher, Farrar Straus Giroux, denounced Dahl’s characterization as a “derisive stereotype.” Dahl conceded the point, responding: “the negro lips thing is taken care of.” Yet, Dahl’s inability to conceive of people of African descent as anything other than caricature remained, despite denials, as did the fact that his legendary book’s stimulating imagination about poverty, chocolate and unexpected salvation had been built on racially toxic assumptions, illusions and images.

Dahl’s book did not exist in a vacuum. Far worse white supremacism appeared in school history and geography textbooks, in pamphlets and newspapers. They were buttressed by exponents of eugenics, especially the Harvard Ph.D. Lothrop Stoddard and Yale’s Madison Grant, who represented a movement with intensely racist and anti-immigrant ideologies that proved immensely popular in the United States prior to World War II and became models for Hitler’s Germany. Nonetheless, Dahl’s work played an important role in perpetuating supremacist ideology and with ingenious imagination depicted Africans as an ignorant, savage people, best suited for enslavement, and whose lives were improved by subordination to white people.

Astonishingly, the 2005 film remake of Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory returned to the original 1964 text for inspiration. Director Tim Burton declared that Dahl’s “politically incorrect” views attracted him to the project, and Gurdeep “Deep” Roy, an Anglo-Indian actor became the dark-skinned stand-in for the Oompa-Loompas.

That so many commentators missed or refused to comment on the book’s depictions of dark-skinned people is testament to the enthralling power of Dahl’s language and imagery. It played as much to the subconscious as to the unconcealed, and given its enduring popularity offers Caribbean nations an important lesson concerning the depth and endurance of racism in the United States. It also affirms James Baldwin’s observation that “white people, with scarcely any pangs of conscience whatever,” are determined “to create, in every generation, only the Negro they wished to see.”

Fall 2020, Volume XX, Number 1

Donald Yacovone is an Associate at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center. The full version of this essay can be read at http://www.processhistory.org/yacovone-dahl-racism/. It is the outgrowth of the larger study he is writing, Teaching White Supremacy: The Textbook Battle Over Race in American History.

Related Articles

A Food for the Goddesses

Maya women were the artisans who invented a panoply of ancient beverages and sauces containing cacao. This association between cacao and women extended to an association with certain Maya goddesses. While originally introduced from South American, the…

Discovering the Taste of Molecules in Chocolate

English + Español

I’m a chemist. And you generally don’t think about chemistry when you have a delicious cup of chocolate. But I have studied the chemical composition of chocolate for 20 years and I would like to share what I have learned with you. For more than three decades…

Keeping the Heritage through a Museum

English + Español

As an architect, I’ve been fascinated by museums and how the design of spaces can influence the experience of the visitor and the meaning of the objects within. Museums are not only repositories of valuable pieces preserved for posterity, but cultural elements…