Salsa Dancers from Cali, Colombia Hop Onto the World Stage

“David and Paulina – 2013 Colombia Salsa Festival” by David and Paulina / CC by 2.0

Once, people of the ocean, from the coast, moved to the valley, hoping to put the Andes between them and Colombia’s decades of killing.

Now, 28 of their grandchildren stood on the cusp of history.

No, they danced on it.

Their $2-a-week-salsa dance classes and rehearsals at Luis Carlos Caicedo’s Nueva Dimension academy on the gritty outskirts of Cali had paid off. The group of grade-schoolers and teens had scored an invitation to participate in the 9th annual West Coast Salsa Congress in Los Angeles this spring.

Without knowing it, they were characters in a chapter still being written into the annals of dance. It’s a story of a culture’s global currents, as hard to follow as the flights of some migratory birds.

The piston-footed, below-the-waist style of dancing salsa developed during the last 40 years in Cali, Colombia’s southwestern city of two million-plus, has been dropping jaws since 2005, from Wellington, New Zealand, to Salt Lake City.

The first two years of the World Salsa Championships, held in Las Vegas, aired on ESPN International and organized by a group called the Salsa Seven, produced two first-place and two top-three finishers from Cali.

Judges at those events were more than impressed.

They were beginning to grouse about how to score the caleños, since their style was completely different from the Cuban and Puerto Rican-influenced steps they had seen.

The same thing has been happening at qualifying rounds for the 2007 championships, slated for Dec. 12-16 at Walt Disney World Resort in Orlando, Fla.

How did this rhythm, sprung from 1970s ferment among Caribbean populations in urban barrios, land in an Andean country’s tropical valley crisscrossed by sugar cane fields? The answer is in the very legs of those kids, a pair of whom wound up qualifying for the 2007 championship based on their L.A. performance. Or better, it’s in the legs of their grandfathers and grandmothers.

The forerunners of today’s acrobatic cadences were actually U.S. sailors who landed on Colombian shores in the 1940s, showing the Charleston and other steps to black Colombian bar-hoppers in Buenaventura, the country’s Pacific port city. The porteños adapted those hops, leaps and flips to Caribbean music, particularly Cuban sounds.

Three decades later, violence pushed the children of those dancers to Cali. The migration from Buenaventura and surrounding areas never stopped, producing one of the largest urban slums in Latin America—Aguablanca.

New York and Puerto Rican salsa also hit Cali in the 1970s, and the city moved to the sound of timbales, congas and brass. With drug cartel financial backing in the 1980s, the music became homegrown. Up to 100 salsa orchestras were formed, seemingly on every corner.

Cali dubbed itself “The Salsa Capital of the World.” The annual December fair became the city’s signature event, as well as a place to pass down steps from generation to generation. Tens of thousands still meet during the week-long bacchanal, trading salsa records and dancing to local and international bands.

If a dance historian was to look for clues about how Cali’s frenetic dance style developed during these decades, he or she would also find that someone at some point discovered that boogaloo, a fusion of rock and Latin percussion, was a real blast to move your feet to if you put the record player on 45 r.p.m. instead of 33 1/3. Add that to the steps originally brought ashore via the feet of sailors, and you have today’s salsa cadence.

Now it’s the children of the urban slum Aguablanca who keep alive Cali’s particular style of salsa dancing, athletic below the waist, seemingly twice as fast as the styles practiced in New York, Los Angeles and the Caribbean, and lacking in twirls and flourishes.

Dancers worldwide are taking notes, says Albert Torres, a member of the Salsa Seven and the driving force behind the world championships. He shows videos of caleños from the first two years at qualifying rounds from Sydney, Australia to Goteborg, Sweden, and everywhere sees the same “What the heck is this?” look on the faces of dancers waiting to compete. The success caleños have seen, combined with the growth of the championships, is leading thousands in Cali to dream of hopping and stepping out of misery.

Riding the wave of popularity that dance competitions have enjoyed worldwide, the event’s third year promises to field competitors from more than 35 countries, after launching in 2005 with 12. The Salsa Seven has picked up contracts with ESPN and its parent company, Disney, along the way.

Still, it’s the dancers from Cali, says Torres, who are “the future of salsa.”

In a phone interview days before his group’s trip to L.A., Caicedo said that community raffles, local performance benefits and family loans provided travel funds. He observed that many of the kids had never seen the ocean, even though their parents or grandparents were from the coast. Decades later, salsa dancing was returning 28 boys and girls to the Pacific Ocean, following the flow of global cultural currents, in reverse.

Related Articles

Review of Going Local: Decentralization, Democratization, and the Promise of Good Governance

This methodologically rigorous and carefully crafted book is an exercise in good scholarship. Like its subject of good governance, it is an embodiment of leadership, performance, accountability and a commitment to constructive policymaking. Merilee Grindl has already made her reputation as a painstaking scholar of governance, bureaucracy and policymaking in Latin America and across the developing world, but Going Local …

Making A Difference: Connecting the Diaspora with Caribbean NGOs

E.One.Caribbean, an initiative based at LASPAU, seeks to engage the Caribbean diaspora in reinvigorating their home countries by providing financial, volunteer, and capacity-building resources to NGOs whose work addresses the social problems that threaten long-term economic and cultural viability. The program was developed by Norris Prevost—a longtime member of the Parliament of Dominica and recent graduate of the …

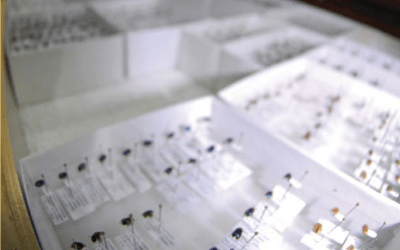

Making A Difference: Insects and Internet: Saving a National Treasure in Hispaniola

On July 11, 2007, the oldest university in the Americas, the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo (UASD), marked the first anniversary of the entry of its natural history collections into the digital global community. These priceless collections record the changing abundances of species over the 20th century, including many species new to science and some that are perhaps already extinct. The collections of insects alone are …