San Romero de América

Beyond Polarization

SAN SALVADOR, El Salvador—María Isabel Delario is crying. Her body is bent, her face buried in her arms, her hands rest on the metal cast depicting the face of a murdered archbishop, a man nominated for sainthood by Pope Francis.

Delario is at the tomb of Archbishop Óscar Arnulfo Romero y Galdámez in the basement of the

Catedral Metropolitana de San Salvador. Some people around her wear shirts emblazoned with the words, “San Romero de América.” “For me he’s still alive” she says. Another worshiper, Carlos Martínez, adds, “Romero’s message was that the Church must work to end inequality. And that was a message that people in power did not want hear.”

Reverence for Romero is evident when you land in San Salvador. A massive sign facing the tarmac announces that you’re arriving at an airport named for Romero. As you enter the country, his image is stamped into your passport. This story is about how Romero’s image continues to be manipulated 36 years after his murder.

How it happened that a man murdered by a government-linked death squad and derided for years by the rich and powerful in El Salvador is now so honored is a key to understanding the country today. In 2015, Romero was beatified by Pope Francis, an Argentine and the first Latin American pontiff, a man who understands Romero’s legacy to millions of people across the Americas.

But his nomination for sainthood has not been met with universal acclaim here.

Retired General Mauricio Ernesto Vargas commanded the Third Infantry Brigade and Military Detachment 4. Both units were accused of human rights abuses during the civil war 1980-1992. Vargas denies the allegations. He was listed in a U.S. Congressional document titled, “Barriers to Reform: A Profile of El Salvador’s Military Leaders.” The son of a founder of the country’s Christian Democratic Party, Vargas went on to become one of the signers of the Peace Accords in 1992. He represented the Salvadoran army in negotiations with Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front/FMLN), the coalition of guerrilla forces that became part of the country’s political establishment after the peace deal and whose current leader is now El Salvador’s president. Today Vargas is a member of the Legislative Assembly as a member of the Nationalist Republican Alliance, or ARENA, which governed El Salvador from 1999-2009.

Speaking of Romero, Vargas said, “His homilies and his words were absolutely manipulated by both the left and Liberation Theology priests,” he told me referring to the movement within the church that calls on priests to actively oppose social inequality and that such work is not decoupled from religion and faith. Romero did not publicly portray himself as a liberation theologian although the issues he addressed dovetailed with some of the movement’s ideals.

“The left infused his words with Marxist-Leninist ideals,” Vargas told me, “and that’s what the guerrillas did in the mountains. They used his words for indoctrination. His image should not be used for political ends.” Vargas said that he wanted to make clear his personal reverence for Romero. “There are people who don’t like him today but that is because they don’t understand what he represented. “I have read his words. He was a pastor and nothing more.”

Others in ARENA, including party president Jorge Velado, have accused the FMLN government of former Salvadoran President Mauricio Funes (2009-2014) of blatant “politicization” of Romero. Funes publicly referred to Romero as his “guide” in government; he renamed the San Salvador airport; he gave a piece of Romero’s bloodstained vestment to Pope Francis and he formally apologized on behalf of the state for the killing, saying the death squad that killed the Archbishop “unfortunately acted with the protection, collaboration or participation of state agents.” All are gestures that critics claim demonstrate the FMLN’s co-opting of Romero for political ends.

Of the current government, Velado said, “Some people from the FMLN are all the time saying that Monseñor Romero was a person very close to us, [that] he used to think like we think. That’s not true.” But Velado added the current FMLN government of Salvador Sánchez Cerén is not “over the top” the way he charges Funes was. Velado pointed out that he, along with Roberto d’Aubuisson Arrieta, son of ARENA founder Roberto d’Aubuisson, were in the delegation of dignitaries attending Romero’s beatification ceremony. FMLN supporters heckled the ARENA members and branded them as political opportunists for attending. The younger d’Aubuisson, now the mayor of a San Salvador suburb, wrote the same day on Twitter, “Let’s not politicize the beatification.”

The perception of Romero being linked to the left undoubtedly delayed his canonization.

Stanford political science professor Terry Karl, an advisor to United Nations negotiators who brokered the peace agreement, also served as an expert witness for the U.S. government in trials involving high-ranking Salvadoran military officials. She helped build the case against Álvaro Saravia, a former head of security at the Legislative Assembly. Saravia was living in California in 2003 before he went into hiding after being served in a civil suit for the Romero murder. In 2004, a U.S. federal judge issued a default judgment finding Saravia liable for extrajudicial killing and crimes against humanity. He is the only person convicted of the killing.

“Romero is still divisive in El Salvador today,” said Karl. “He was the voice of human rights in El Salvador and he believed in accountability. All parties want to claim him. The fight over Monseñor Romero is the fight for both justice and memory.”

Romero led the Catholic Church in El Salvador from 1977, when he was appointed Archbishop, until he was murdered March 24, 1980—shot by a sniper with a single bullet through the chest—while saying Mass in the chapel of the Divine Providence Hospital. He had lived an austere life in a casita at the cancer hospital. A 1993 United Nations Truth Commission report concluded that the intellectual author of the crime was Roberto d’Aubuisson. He was 47 when he died of throat cancer in 1992 and some Salvadorans claim that was God’s revenge for the Romero murder.

The day before he was killed, Romero delivered a memorable homily. As the nation listened on the Archdiocese’s radio station, he spoke about a divided Salvadoran society and about repression. He addressed the Salvadoran military, national guard and police directly, exhorting them not to kill their own brothers and sisters, the campesinos. He declared that the law of God prohibits killing and that divine law supersedes human law.

“No soldier is obliged to obey an order to kill if it runs contrary to his conscience.” Romero said. “I implore you, I beg you, I order you in the name of God. Stop the repression!” His words were met by applause from the pews but ultimately cost him his life. Romero’s murder helped propel El Salvador into a civil war between leftist guerrillas and a right-wing military government actively supported by the United States.

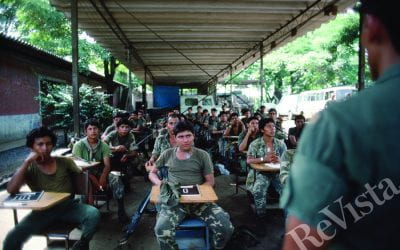

The United States funded the Salvadoran military as a purported buffer against the spread of Communism in the Americas. In 1979 the Sandinistas had toppled the U.S.-backed Somoza dictatorship in neighboring Nicaragua, and newly elected U.S. President Ronald Reagan was loathe to let a similar scenario unfold in El Salvador. Central America was a focus of U.S. foreign policy the way Iraq, Syria and Iran are today. It was against that backdrop that the manipulation of Romero’s image began.

He had been selected as Archbishop because he was deemed to be a conservative, pliable prelate, a man who would not disturb the political status quo in which a few families and the military controlled the vast majority of the country’s resources. Later his image would be co-opted by the leftists, including guerrillas and their supporters who sought to imply Romero was a supporter.

But Romero condemned atrocities on both the left and right. The majority of his criticism was directed at the military and state security forces because, as the U.N. report later concluded, they committed the vast majority of human rights abuses at the time.

Three weeks into his tenure as Archbishop came a turning point that started Romero on a path that ultimately led to his beatification in 2015. Romero’s colleague, Jesuit priest Rutilio Grande, was killed along with an old man and a young boy as the three made their way to a church in the village of El Paisnal.

Romero suspended classes in Catholic schools for three days. He ordered the cancellation of Mass throughout El Salvador. Instead, he gathered all his priests for a single service in the capital attended by 100,000 people. He ignored warnings from the Papal Nuncio not to hold the Mass for fear of offending the government. The Archbishop then refused to attend any state occasions, including the swearing-in of a new president, General Carlos Romero, until the Grande murder was investigated. No such investigation took place.

Now Romero was gaining in popularity, his image transformed into that of an ardent defender of the poor. That same image meant Romero was reviled by the right. The right accused Romero of being a fellow traveler with left-leaning movements that included the FMLN.

OPPOSITION FROM THE OLIGARCHY

José Jorge Simán, affectionately known as “Don Pepé,” is a scion of a prominent and wealthy family in El Salvador. He shuns labels such as “member of the aristocracy” but admits he fits the bill. Simán, a former leader of the Catholic laiety group, Comisión Nacional de Justicia y Paz, is the author of Un Testimonio, a memoir of his friendship with Archbishop Romero. That friendship made him a rare breed among El Salvador’s upper class.

“People with money never understood Romero,” said Simán in a recent interview in his modest office festooned with photographs and images of the slain cleric. “They told me I was crazy, I was a Communist, that I didn’t know what was going on, that I was being deceived.”

“At that time, most of the information you got was completely distorted. So logically, people never knew him,” Simán continued. “And this is our challenge now, that people know him, not through the point-of-view of left or right, but from the point-of-view of Romero.”

When asked what Romero’s perspective was, Simán said it was to oppose oppression, be it military or social. “He followed Jesus and that is the point of reference,” Simán concluded.

OPPOSITION WITHIN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH

Across town, at the Iglesia San Francisco de Asís, the Auxiliary Bishop of San Salvador, Monseñor José Gregorio Rosa Chávez, said the hierarchy of the Catholic Church never liked Romero following his conversion from passive priest to passionate defender of the poor.

“Romero spoke out against violence, structural violence in the country and inequality,” Rosa Chávez said. “The story about the 14 families (controlling the vast majority of the country’s wealth) was true.”

“There was never true freedom here and that was the situation that Romero stepped into when he became Archbishop. But a key point to remember is that this all took place during the Cold War.”

“He confronted violence in the country and he also was involved in geopolitics,” he said, referring to Romero’s letter to U.S. President Jimmy Carter asking him to send food to El Salvador, not military aid.

Rosa Chávez said Romero knew he was a target, that he’d reconciled himself with the notion that he might be killed. “He was aware of what he was getting into. And he spoke out during a brutal fight between east and west that played out here. He was a victim of that confrontation.”

Rosa Chávez met with Pope Francis October 30, 2015 at the Vatican. He watched the Pope make official what had long been common knowledge in El Salvador, that Catholic priests and bishops had defamed Romero before and after his murder.

“I was a young priest then and I was a witness to this,” the Pontiff told a group of Salvadoran bishops and pilgrims. “He was defamed, slandered and had dirt thrown on his name, his martyrdom continued even by his brothers in the priesthood.”

Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia supervised the beatification process at the Vatican. He told reporters in 2015 that he saw proof of that opposition. “Kilos of letters against him arrived in Rome,” he explained. “The accusations were simple. He’s political, he’s a follower of Liberation Theology.” He added that unnamed Salvadoran ambassadors to the Holy See had asked the Church to stop the process.

Romero’s brother Gaspar, in discussing the assassination of the Archbishop, said, “He saw the injustice and poverty that people were living with. The oligarchy hated him. They wanted to silence his voice but they didn’t succeed and they won’t ever succeed.”

EL MOZOTE AND ROMERO

Today, paramilitary death squads and guerrillas have been replaced by organized crime and drug traffickers. The inequality Romero railed against remains. And so does his image. It is omnipresent.

In Arambala, in Morazán Department, a mountainous zone that was the cradle of the guerrilla movement, a mural depicts four images under a banner that reads, “Junto al Pueblo Seguimos Luchando.” (We’re still fighting alongside the people.)

The four images are of Che Guevara, Óscar Romero, Schafik Handal, a deceased FMLN leader, and Farabundo Martí, executed in 1932 after a peasant uprising he helped organized was put down.

Romero’s photo also adorns the wall of the church in the mountain hamlet of El Mozote, site of a massacre December 11, 1982, of hundreds of peasants by the same Atlacatl battalion implicated in the murders of six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her daughter in 1989. Romero’s death, the Jesuit murders and El Mozote are all touchstone events in the story of modern El Salvador. All represent wounds that have not healed.

Every day in the village church, steps away from the village square where men and women were separated before being executed, Romero is mentioned in prayers. “He was a true leader,” said María Delfina Argueta. She guides visitors around one of the massacre sites. “He died for speaking the truth. I tell you right now that Romero still lives with us,” she said. Before he died, Romero wrote that violence would continue to plague the country until structural inequality was addressed.

Former Defense Minister General José Guillermo García was deported from the United States January 8, 2016. The expulsion followed a 2014 ruling in U.S. courts that Guillermo García assisted or otherwise participated in the assassination of Romero, the murders of four American churchwomen, two U.S. labor advisors and the massacre at El Mozote, not to mention thousands of Salvadoran citizens. But it’s unclear if he’ll ever have to answer for the crimes.

In 1993, days after the U.N. declared that Roberto D’Aubuisson planned the Romero killing, the ARENA government passed an amnesty law. The military, the death squads and FMLN would never be held to account. It is within that vacuum of historical responsibility that Romero’s image continues to be manipulated.

Spring 2016, Volume XV, Number 3

Lorne Matalon is a reporter at the Fronteras Desk, a collaboration of National Public Radio stations focused on Mexico and Latin America. He began reporting on Latin America in 2007 from Mexico City for The World, a co-production of the BBC World Service, Public Radio International and WGBH, Boston.

Related Articles

The Boy in the Photo

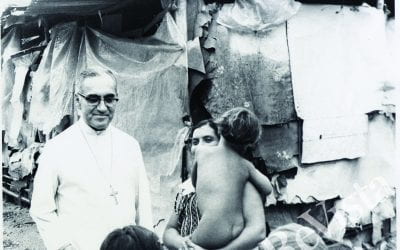

The mangy dogs strolled everywhere along the railroad track. I remembered dogs just like them from the long-ago day in La Chacra in 1979 with Archbishop Óscar Romero, just months before he was killed…

Beyond Polarization in 21st-century El Salvador

My father was a civil engineer who worked for the government during the civil war years. He specialized in roads and had to spend several days a month traveling to remote places in El Salvador. I was 10 in 1986, and I remember my mom asking my dad…

El Salvador: Editor’s Letter

I had forgotten how beautiful El Salvador is. The fragrance of ripening rose apples mixed with the tropical breeze. A mockingbird sang off in the distance. Flowers were everywhere: roses, orchids, sunflowers, bougainvillea and the creamy white izote flower…