Seeds of Gold, Local Entrepreneurs

Ecuador’s Cacao Boom of the Late 1800s and Early 1900s

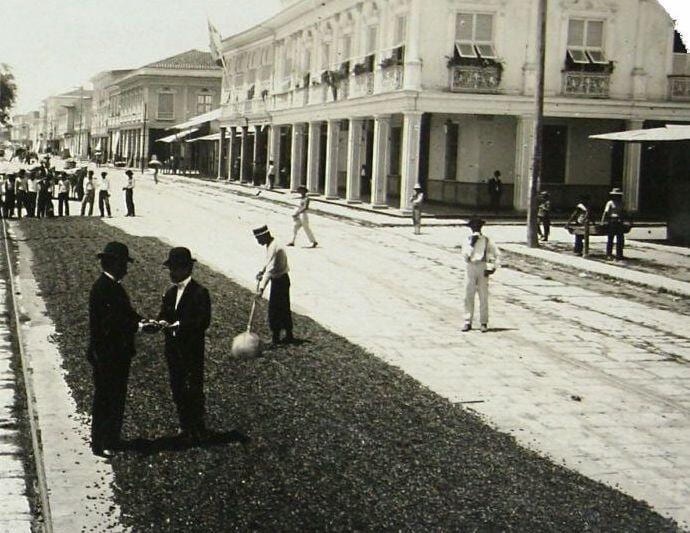

Cacao drying on Guayaquil’s malecón (or waterfront), early 1900s. Photo courtesy of Cecilia Estrada de Icaza, Guía Histórica de Guayaquil

Approaching Guayaquil in 1879 to assume his duties as French vice consul, Charles Wiener assessed the port city and nearby farms. “A tropical Holland,” he later declared.

Guayaquileños have always taken Wiener’s remark as a well-deserved compliment, even if it might have been subtly ironic. But regardless of what the diplomat meant to say, any seasoned traveler 141 years ago was aware that the Frenchman’s new posting differed sharply from coastal areas to the north and to the south. Owing to torrential rainfall, northwestern Ecuador, western Colombia and points beyond were thickly forested. On the other side of Guayaquil were the Peruvian littoral and northern Chile, past which Wiener had just sailed. That segment of South America is a desert, both because the cold-water Humboldt Current is just offshore and because the Andes Mountains block the passage of moisture-laden clouds out of the Amazon Basin.

Neither arid nor a jungle, the watershed of the Río Guayas (which empties into the Pacific Ocean a few miles south of Guayaquil) is an ideal setting for agriculture. Soils are fertile and precipitation during the wet season, which begins in December and lasts four to five months, is in line with farmers’ needs. Also, a major advantage exists over the Caribbean Basin, which produces the same crops. Aside from inclement weather during El Niño years, western Ecuador is free of hurricanes, which are an annual threat in places such as Central America and Cuba.

In addition to underscoring the agricultural potential of the Río Guayas watershed, which happens to be nearly as large as the Netherlands, Wiener could have had the hustle and bustle of Guayaquil’s businessmen in mind when he stated there was a tropical Holland in western Ecuador. This commercial activity related to the long-time remoteness of the city from seats of government. During the colonial era, southern Ecuador was ruled from Lima, hundreds of miles down the coast. And through the early 1900s, when a railroad was extended up into the mountains, a grueling journey on foot or horseback was required to reach Quito, Ecuador’s Andean capital. Thus, Guayaquil was an unpromising location for the pursuit of governmental favors. Instead, the port city became what it remains today: a haven for entrepreneurs.

With timber extracted from nearby forests, Guayaquil’s entrepreneurs constructed more ships from the 1500s through the early 1800s than anyone else between the Bering Strait and Cape Horn. Starting in the late 1840s, businessmen from western Ecuador organized the production of tightly woven straw hats, which they sold to gold miners crossing the Panamanian Isthmus on their way to California. Those Forty-Niners having mistaken the origin of their purchases, the headgear is still made in Ecuador yet marketed as Panama hats.

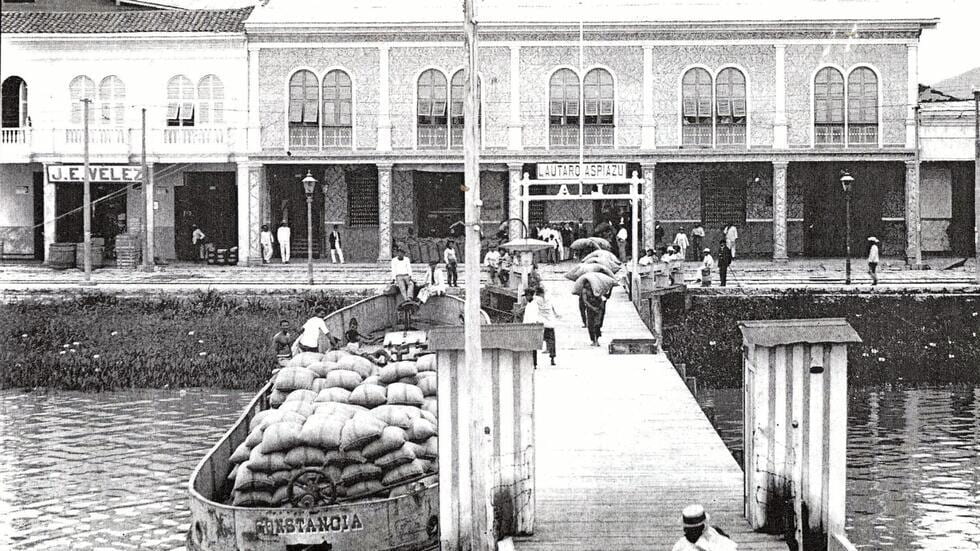

- Office, warehouse and dock on Guayaquil’s malecón (or waterfront) belonging to Lautaro Aspiazu, a leading cacao exporter in the early 1900s. Photos courtesy of Cecilia Estrada de Icaza, Guía Histórica de Guayaquil.

- Cacao being spread to dry on Calle Panama in Guayaquil, early 1900s. Photos courtesy of Cecilia Estrada de Icaza, Guía Histórica de Guayaquil

The achievements of local entrepreneurs notwithstanding, Guayaquil was not an easy place to strike it rich. La perla del Pacífico, as the city’s residents called it, was a notorious hotbed of yellow fever and other mortal diseases. Additionally, western Ecuador was far from its most important customers. Prior to the completion of the Panama Canal in 1914, a vessel heading for Europe or the eastern United States first had to traverse half the length of the Pacific Ocean before doubling Cape Horn, often in the teeth of raging winds and waves, then travel nearly the entire length of the Atlantic Ocean before docking in, say, Liverpool or New York.

Not many years before Wiener’s arrival, undertaking this journey for the sake of commerce, alone, was rarely worth the time, expense and risk.

The Cacao Boom

The quickening of business in western Ecuador during the late 19th century stemmed from the development of novel products made from a pre-Columbian staple, called xocoatl by the Aztecs and pepa de oro (seed of gold) by Ecuadorians. The Dutch pioneered chocolate candy in 1828. In 1875, Daniel Peter, a Swiss confectioner, created a solid milk chocolate by combining powder extracted from the seeds (or beans) of cacao trees with condensed milk, which his neighbor, Henri Nestlé, had invented. Within a few years, chocolate bars and soda fountains were fixtures of popular culture, not least in the United States.

Demand for cacao beans skyrocketed. Between 1870 and 1897, global per-capita consumption of coffee and tea increased by 25 percent and 100 percent, respectively. Meanwhile, per-capita consumption of cacao went up nine-fold. Global exports doubled between 1895 and 1905 before doubling again between 1905 and 1915.

Among European manufacturers, arriba (meaning up-river) cacao was especially prized for its strong, bitter flavor. Different from permanent crops such as coffee, another long-time Ecuadorian export, the cacao shipped overseas during the 1800s and early 1900s was for most intents and purposes a non-timber forest product, like fruit collected to this day from moriche palms in eastern Peru and other parts of the Amazon Basin. Trees bearing arriba cacao regenerated naturally and flourished with little management in deep soils close to the Río Guayas and its tributaries. On average, a hired hand could tend 12½ acres of these trees; this absence of labor intensity was an advantage as long as yellow fever, malaria and other diseases were rampant. Moreover, cacao destined for chocolate factories on the far side of the world could withstand a year or more of rough handling—in canoes and other watercraft used to ferry cargo to Guayaquil, while spread out to dry on streets and sidewalks in the port city, and by stevedores hoisting 100-pound bags of beans on their backs.

Consisting at first mostly of the arriba variety, annual cacao shipments out of Guayaquil and the smaller port of Bahía de Caráquez rose from 12,000 tons during the 1880s to 18,500 tons during the 1890s. By 1900, Ecuador was the world’s leading exporter and sales to international customers were still growing. Those sales peaked at nearly 41,000 tons a year during the second decade of the 20th century.

Just as ship building in Guayaquil and the Panama hat business had been in Ecuadorian hands, producing and exporting the pepa de oro were national ventures. Large plantations owned by elite coastal families were the source of four-fifths of the total harvest, which allowed some of those families to live well and entertain lavishly at times in Paris. However, a nascent middle class also emerged during the cacao boom, thanks to the brokering of cargo space, financing and other services offered to exporters in Guayaquil.

The Boom Ends

Before the turn of the 20th century, plantation owners in the Río Guayas watershed were finding it impossible to keep pace with the escalating global demand for cacao, so different varieties were brought in from Trinidad and Venezuela. These varieties thrived away from riverbanks, in places where trees yielding arriba cacao did not do well. Aggregate output consequently increased, though at the expense of a deterioration in quality.

Industrial buyers in Europe and North America immediately detected this deterioration. As arriba cacao accounted for ever-smaller shares of Ecuadorian output, those buyers gradually turned to other sources of supply, where inferior cacao could be had more cheaply. Worse, varieties introduced from the Caribbean Basin proved to be susceptible to a local fungus, Moniliophthora roreri, responsible for Frosty (or Monilia) Pod Rot, which started to take a toll on production in 1916.

This article’s coauthor with Juan X. Marcos – her husband’s employer as well as the business partner of the greatest of Guayaquil’s entrepreneurs, Luís Noboa. Noboa was an independent street-vendor before being hired at 12 years of age by Marcos’s father in 1928. Photos courtesy of personal collection of Lois Roberts

Following World War I, competition intensified from plantations in Africa and elsewhere and the market value of cacao declined along with other commodity prices. In 1922, Witches’ Broom caused by another fungus, Crinipellis perniciosa, started damaging trees that were the source of arriba cacao. No counter-measures were found either for Witches’ Broom or for Frosty Pod Rot, so average annual production from 1921 through 1924, 36,000 tons, was 12 percent below the levels registered during the previous decade.

Lower export volumes and sliding cacao prices reduced taxes levied on exports, which had always been a mainstay of public finance. Unwilling to cut spending, the authorities in Quito borrowed heavily from the Banco Comercial y Agrícola (BCA)—a lending institution in Guayaquil that had been authorized since 1915 to print the currency it lent the government. This monetization of fiscal deficits caused inflation to accelerate and the Ecuadorian sucre to devalue. In 1922, rising food prices sparked civil unrest, which the military suppressed violently. Young officers who seized power in 1925 repudiated debts to the BCA, which brought down the bank. As the downward spiral continued, Ecuadorians who had borrowed internationally, including the owners of a few cacao estates, were ruined.

Green Gold and Beyond

By the late 1930s, Ecuador’s share of global cacao supplies had all but disappeared. Still, a network of capable entrepreneurs remained in Guayaquil, together with businesses specializing in export-related services. As a result, new opportunities for trade were seized. During World War II, merchants based in the port city exported rice harvested from nearby farms. After hostilities ceased in 1945, those same merchants played a pivotal role as their country quickly became the world’s top supplier of bananas—oro verde (green gold), as Ecuadorians described the fruit.

- Banana stems on the Guayaquil’s waterfront, early 1950s. Photos courtesy of personal collection of Lois Roberts

- Stevedores loading banana stems in Guayaquil, early 1950s. Photo courtesy of personal collection of Lois Roberts

The national government supported banana development at critical times – especially from 1948 to 1952, when the democratic administration of President Galo Plaza improved rural infrastructure and provided farm credit. And as various growers recognized, United Fruit introduced essential agricultural technology during the post-war period, when the company never possessed more than 3 percent of the acreage planted to bananas in and around the Río Guayas watershed. But the most distinctive feature of Ecuador’s tropical fruit industry has been and continues to be a banana market worthy of the name. The supply side of that market comprises hundreds of independent planters, the vast majority of whom have holdings of 50 to 1,000 acres. On the demand side are dozens of exporting firms, few of which are foreign and none of which accounts for more than 10 percent of total shipments.

Ecuadorian exporters learned long ago how to move perishable goods from inland farms to buyers thousands of miles across the sea and to crack markets where multinational firms rarely ventured. Thus, the country’s tropical fruit bonanza, which began 75 years ago, shows no sign of ending. Furthermore, Ecuador has never been a banana republic, under the thumb of an enterprise such as United Fruit. Instead, its growers and exporters undermined the near-monopoly United Fruit enjoyed as long as it dominated banana production in the Caribbean Basin—ultimately benefiting consumers around the world in the form of lower banana prices.

Experience gained in the tropical fruit business has been harnessed in the marketing of other perishable goods overseas. During the 1980s, Ecuador became the leading exporter of farm-raised shrimp in the Western Hemisphere. The country is also a major supplier of cut flowers, most of which are produced in Andean valleys within reach of Quito’s international airport.

Ecuador has a future in cacao as well, though not as a source of undifferentiated bulk commodities. Competing head to head against the world’s leading suppliers of “ordinary” cacao in West Africa is unappealing, given that rural wages are extraordinarily low in that region. As an alternative, the South American nation specializes in “fine” product, which comprises about 5 percent of the world market by volume and which fetches higher prices.

- An open cacao pod and its seeds held by Don Fabian. Photo by Hannah Levit

- Seed-bearing pods growing on young cacao trees. Photo by Oliver Rich

Competing on the basis of quality likewise makes sense in chocolate manufacturing, which is a new development in Ecuador. So that overall transportation costs can be minimized, the industrial-scale mixing of cacao products with milk usually happens in dairying regions close to millions of sweet-toothed consumers—as Milton Hershey demonstrated at the turn of the 20th century when he began making chocolate bars amidst the green pastures of southeastern Pennsylvania. Reluctant to take on the Hershey Company and other giants of the industry directly, Ecuador’s chocolatiers specialize in high-end goods marketed as gourmet, organic or both.

These businessmen and women are following a path blazed by their entrepreneurial forebears, who more than a century ago made sure that their tropical Holland was an early beneficiary of the worldwide craze for milk chocolate.

Fall 2020, Volume XX, Number 1

Douglas Southgate is emeritus professor of Agricultural, Environmental and Development Economics at Ohio State University. Lois Roberts formerly taught Latin American history and culture in the Department of National Security Affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School. This article is based on the doctoral dissertation Roberts completed at the University of California at Los Angeles and on Southgate’s and her book: Globalized Fruit, Local Entrepreneurs (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

Related Articles

Between America and Europe

On Tuesday, September 9, 1645, at 12 noon, the cocoa trader Antonio Méndez Chillón was arrested at his home in Veracruz (New Spain) by the Inquisition commissioner and charged with Jewish heresy. This episode, which was far from being isolated, helps shed…

Divine Decadence or Business Turnaround?

English + Español

Back in 2006, we became intrigued about a chocolate company in Venezuela. Rohit had done quite a bit of work on companies that were integrating country of origin into their product branding. He called it the Provenance Paradox. As Director of HBS’s Latin America…

Small (Labor) Truths

In 2005, a company named Taza debuted a new way to do chocolate. The disc-shaped bars produced in their Somerville, Massachusetts factory were minimally processed from from ethically-sourced cacao and contained only ingredients that might…