About the Author

Verónica Isabella Nutting is a junior at Harvard College studying Computer Science with a secondary in Government from Buenos Aires, Argentina and Wheeling, West Virginia.

Acerca del Autor

Verónica Isabella Nutting está en su tercer año en Harvard donde estudia Informática y Gobierno. Es mitad Argentina y mitad Americana y vive en Buenos Aires, Argentina y Wheeling, West Virginia.

Six-and-a-Half Weeks in Buenos Aires During the Corona Crisis

Argentina has been both applauded and criticized for proactive and severe action amidst the corona crisis. As a dual Argentine-American citizen, I was able to go home to Buenos Aires and remain in quarantine there from March 15 to April 29, only returning to the States with my sister when Argentina suspended all inbound/outbound flights until September 1. It was a very difficult decision to leave Argentina and my mother and brother who stayed there.

I’ll quickly give some demographic, political, and economic context that I think is helpful for understanding Argentina’s response to the corona crisis. Argentina is a country of over 40 millionpeople, nearly 32% of which live in the larger metropolitan area around Buenos Aires. As of 2019, 35.5% of the country lived below the poverty line. This is higher than many of its neighbors–Brazil had a poverty rate of 25.3% in 2018 and Uruguay’s was 8.1% in 2019–as well as the U.S., which had a poverty rate of 11.8% in 2018. Amidst the coronavirus pandemic, experts estimate the Argentine poverty rate has already risen to 45%.

Argentina has a turbulent political history that includes years of Peronism and six coup d’états in the twentieth century, the last which led to a harsh military dictatorship from 1976 to 1983. The current president, left-leaning Alberto Fernández, was elected a few months ago in October 2019. Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who was herself president from 2007-2015 and has faced multiple corruption charges, serves as vice president. Although this regime change fits into the larger “Left Turn,” it also sets Argentina apart from other currently rightwing Latin American neighbors. Amidst the corona crisis, Argentina has withdrawn from future negotiations with the Mercosur trade bloc.

Lastly, I’ll briefly discuss the Argentine economy. From having the seventh highest income per capita in the world in 1908 and a wealth of natural resources including minerals, agriculture, and energy, Argentina presents an interesting economic puzzle. Argentina has defaulted eight times and, amidst the corona crisis and the continued devaluation of the Argentine Peso, there is international concern that the country will default a ninth time soon. With all of this in mind, I will discuss what being home in Buenos Aires was like during the early weeks of the corona crisis, starting from the very beginning.

On Tuesday March 10, 2020, Harvard announced that classes would resume virtually after spring break. I called my parents and we decided that it would be best if I went home to Buenos Aires. That day, Argentina imposed a 14-day home quarantine for travellers returning from the US, so I knew as early as then that going home would be completely different this time.

As that week went on, alongside midterms, moving out, and goodbyes, I kept my eye on Argentina’s response to the corona crisis. On Thursday March 12, Argentina declared a state of health emergency for a year. The country began planning for the closing of universities, museums, restaurants and other public spaces and mass gatherings, as well as fixing hand sanitizer and mask prices.

At that point, mandatory quarantine was expanded to include not only travelers returning from affected areas but also people in close contact with them and suspected cases. Additionally, the decree suspended all international flights coming from areas of risk for thirty days, with some exceptions for repatriation flights. People found to be violating quarantine or other health measures would be faced with serious sanctions, including prison sentences of up to two years.

My younger siblings and I were not quite sure what this meant for us flying back from the States to Buenos Aires that weekend. Officially, flights departing from the U.S. before Monday March 16 would be allowed to land. Still, we were pretty nervous. I felt that destabilizing sense of “What is going on” that weeks later has become the norm. What did the 30-day decree mean for my family sprinkled across the US? And for all my Argentine friends studying abroad in Europe and Australia?

On Saturday March 14, I flew from Boston to Houston. At the airport I met up with my father and brother. As we boarded our overnight flight to Buenos Aires, as we had done countless times before, we remarked that everything seemed normal. Maybe not that much had changed? After all, my sister, who had flown to Argentina the night before, had not had any problems.

However, a few minutes later, the gate agents stopped boarding, announcing that they had just heard that only Argentine citizens and residents would be accepted in Buenos Aires and that all other passengers could no longer fly. About half of the passengers, including us, had already boarded the plane, so they checked our documents one-by-one, making sure we could all enter the country and removing a few passengers who could not.

A bit over twelve hours later, my dad, brother and I were on our way to our apartment in the city. My mom had set everything up such that we could all safely complete our 14-day mandatory quarantines from the confines of our home. Things were looking up. Though the past days had been sobering for each of us, we were tired from midterms and looking forward to settling into our isolated lives.

A few days later, the country entered into a nationwide lockdown, with mandatory strict quarantine for all from March 20th through March 31st. We were not fazed at all at the time. However, this quarantine would eventually extend for weeks, with no clear end in sight. Now looking back, I realize that it makes more sense to think about stages of quarantine rather than end dates. The nationwide, mandatory quarantine would be extended to April 12th, April 26th, and May 10th with limited relaxation and reopening measures. Currently, most expect strict quarantine to continue at least until June.

In total, I spent 45 days under strict home quarantine. Academically, the first week corresponded to spring break and the last five-and-a-half to the second half of the spring semester. During those 45 days, I left my home five times. On March 31st, I went to the pharmacy. On April 10th, I left my house and bought carrot cake. On April 14th, I dropped some supplies off at my grandma’s house. On April 21, I went to the supermarket. Lastly, on April 27, I went to a doctor’s appointment.

During these short visits outside, I saw very few other people on the streets of Palermo, the neighborhood where I live. This was pretty surprising to me as I had not been sure if others were observing the quarantine as strictly as we were in my family. After all, I had read countless scandals in the news of people who had violated quarantine and infected others.

However, it appeared that most people around me were indeed staying inside their homes. Most Argentines surveyed throughout my time in Argentina supported preventative quarantine measures, despite their being significant concern about the toll it was taking on the economy and the most vulnerable Argentines. Indeed, a large proportion of the people I saw outside were homeless, highlighting how the corona crisis is exacerbating socioeconomic inequality.

The only other people I saw outside were police officers, delivery people on bikes and motorcycles, people wearing masks and often gloves carrying reusable supermarket bags, and many people walking their dogs. I noticed a steady decline in the overall density of people outside from the first time I left my apartment to the last. Additionally, there was a steady increase in health measures, with hand sanitizer stations being supplemented with at-the-door temperature checks.

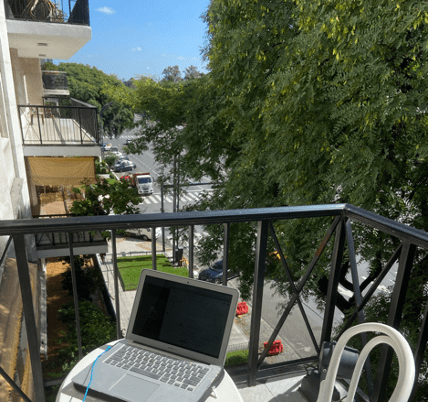

Overall, I cherished my visits outside. They were freeing and refreshing. I tried to make the most of my time inside too. Although virtual classes took up most of my hours in quarantine, I also kept busy with hobbies and other projects. I signed up for the government volunteer program “Mayores Cuidados” but was never matched with anybody. On days when I felt too cooped up, which were most days, I would go to the balcony and read or do stretches. I’d see many of my neighbors there too, on their balconies. Some evenings, we’d all come back out to clap for health-care workers. Other nights, I could hear the loud echoes of cacerolazos, where people would bang on pots and pans in protest of the government releasing prisoners, not lowering politicians’ salaries, and other issues.

As the United States surpasses 1 million confirmed cases while Argentina has fewer than five thousand to date, it becomes less and less clear to me that leaving was the right decision. In this time where I’m reading the news more than ever, I feel simultaneously very connected and very disconnected from the rest of the world.

Semanas y Media en Buenos Aires durante la Crisis del Coronavirus

Foto desde el balcón de cuarto piso en Buenos Aires y la vista desde el cuarto de Verónica.

Ante la crisis del coronavirus, el gobierno argentino ha actuado de forma severa y proactiva, por lo cual ha sido apoyado y criticado por los medios internacionales. Como yo tengo doble ciudadanía de Argentina y Estados Unidos, pude volver a Buenos Aires donde estuve en cuarentena desde el 15 de marzo hasta el 29 de abril, volviendo a EEUU con mi hermana cuando Argentina suspendió todos los vuelos hasta el 1 de septiembre. Fue una decisión muy difícil irme de Argentina y dejar a mi mama y a mi hermano que se quedaron ahí.

El anochecer afuera del Paseo Alcorta en Palermo, abril 2020.

Ahora voy a dar un poco de contexto demográfico, político, y económico que creo que ayuda a aclarar las acciones de la Argentina ante la crisis de corona. Argentina es un país de más de 40 millones de personas, alrededor del 32% de las cuales viven en el Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires. En el 2019, 35,5% del país vivía por debajo de la línea de pobreza. Esta figura es alta en comparación a otros países de la región. En el 2018, Brasil tenía una tasa de pobreza del 25,3% y, en el 2019, la tasa de pobreza era del 8,1% en Uruguay. Y Estados Unidos, por ejemplo, tenía una tasa de pobreza de 11,8% en el 2018. En medio de la pandemia del coronavirus, expertos estiman que la tasa de pobreza argentina ya aumentó al 45%.

Argentina tiene una historia política turbulenta que incluye años de Peronismo y seis golpes de estado en el siglo veinte–el último que resultó en una dictadura militar del 1976 al 1983. El presidente actual, izquierdista Alberto Fernández, fue electo presidente hace unos meses en octubre del 2019. Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, quien fue ella misma presidente del 2007 al 2015 y enfrenta cargos por corrupción, es vicepresidente. Aunque este gobierno encaja en la “marea rosa,” actualmente marca una diferencia entre Argentina y sus vecinos derechistas Latinoamericanos. Recientemente, en medio de la pandemia, Argentina se ha retirado de negociaciones futuras con el bloque comercial Mercosur.

Por último, voy a comentar brevemente sobre la economía argentina. En el 1908, Argentina tenía uno de los ingresos per cápita más altos del mundo. El país también goza de una gran riqueza de recursos naturales, especialmente en los sectores de minería, agricultura, y energía. Al mismo tiempo, ha incumplido ocho pagos de deuda y, en medio de la crisis de corona y la continuada devaluación del peso argentino, hay preocupación internacional que el país incumplirá una novena vez. Con todo esto en mente, voy a contar un poco cómo fue estar de vuelta en Buenos Aires durante las primeras semanas de la corona crisis, empezando desde el principio.

El 10 de marzo, un martes, la universidad de Harvard anunció que las clases se reanudarían virtualmente después de las vacaciones de primavera. Hablé con mis papás y decidimos que sería mejor que yo vuelva a Buenos Aires. Ese día, Argentina anunció que viajeros que volvían de EEUU tendrían que permanecer en cuarentena domiciliaria durante un periodo de 14 días. Ya entonces sabía que volver a casa iba a ser muy diferente.

Esa semana, entre que rendía exámenes parciales, hacía mis valijas, y me despedía de amigos, leía las noticias argentinas todos los días. El jueves 12 de marzo, ví que Argentina declaró una emergencia sanitaria por un año. Entonces, el país empezó a prepararse para el cierre de facultades, museos, restaurantes, y otros espacios públicos y fijó los precios de alcohol en gel y de barbijos.

En ese momento, la cuarenta obligatoria se amplió para incluir no solamente a los viajeros volviendo de áreas afectadas, pero también a las personas en contacto cercano con ellas y también a casos sospechosos. Adicionalmente, el decreto suspendió todos los vuelos internacionales originando de áreas de riesgo por 30 días, con algunas excepciones para vuelos de repatriación. También se agregaron sanciones por incumplimiento de la cuarentena y otras medidas sanitarias que incluían multas y hasta dos años de prisión.

Mis hermanos y yo no estábamos seguros como iba a ser volar desde EEUU a Buenos Aires ese fin de semana. Oficialmente, los vuelos partiendo de EEUU antes del lunes 16 de marzo iban a poder aterrizar en Ezeiza. Igual, estábamos un poco nerviosos. Me preguntaba todo el tiempo a mi misma, ¿qué está pasando? Aún hoy sigo sin una sensación de estabilidad general. ¿Que significaba la prohibición de treinta días para mi familia esparcida por todo EEUU? ¿Y que les iba a pasar a mis amigos argentinos que estaban estudiando en Europa y Australia?

El sábado 14 de marzo, volé de Boston a Houston. Me encontré en el aeropuerto con mi hermano y mi papa. Mientras abordábamos nuestro vuelo a Buenos Aires, como habíamos hecho tantas veces antes, todo parecía normal. ¿Por ahí realmente no había cambiado nada? Después de todo, mi hermana, quien había viajado a Argentina la noche anterior, no había tenido ningún problema al entrar al país.

Sin embargo, algunos minutos después, los agentes de puerta frenaron el embarque, anunciando que acababan de escuchar que solo ciudadanos argentinos y residentes serían aceptados en Buenos Aires y que otros pasajeros no podían viajar. Nosotros y casi mitad de los otros pasajeros ya estábamos sentados en el avión, entonces los azafatos pasaron y nos chequearon los pasaportes uno por uno. Terminaron teniendo que sacar a algunos pasajeros del avión.

Un poco más de doce horas más tarde, mi papá, mi hermano, y yo estábamos en camino a nuestro apartamento en Capital. Mi mamá ya había preparado todo para que podamos cumplir nuestras cuarentenas desde los confines de nuestra casa. Nos sentíamos aliviados de haber llegado bien a casa y teníamos ganas de instalarnos en nuestras vidas aisladas.

Unos días después, el país entró en cuarentena obligatoria nacional para todos los argentinos, del 20 al 31 de marzo. Esto nos sorprendió un poco, pero la verdad es que en ese momento no nos imaginábamos cuánto se iba a terminar extendiendo la cuarentena. Ahora, retrospectivamente, me doy cuenta que en realidad tiene mucho más sentido pensar del fin de la cuarentena en términos de etapas y no fechas exactas. La cuarentena nacional se extendería hasta el 12 de abril, el 26 de abril, y el 10 de mayo, con relajaciones y aperturas limitadas. Actualmente, se espera que la cuarentena durará hasta a lo menos principios de junio.

Calles vacías de Palermo durante la crisis de corona.

En total, pase 45 días bajo cuarentena domiciliaria estricta. Académicamente, la primera semana correspondió a mis vacaciones de primavera mientras que las últimas cinco y medias correspondieron a la segunda mitad del semestre. Durante esos 45 días, salí de mi casa cinco veces. El 31 de marzo, fui a la farmacia. El 10 de abril, salí a comprar budín de zanahoria. El 14 de abril, fuí a la casa de mi abuela a dejarle algunas cosas. El 21 de abril, fuí al supermercado. Y, por último, el 27 de abril, fuí a una clínica a hacerme un estudio médico.

Durante estos viajecitos afuera, ví muy pocas otras personas en las calles de Palermo, el barrio donde vivo. Esto me sorprendió muchísimo porque no tenía idea si otras personas estaban cumpliendo la cuarentena. Aunque en mi familia lo estábamos tomando muy en serio, todo el tiempo aparecían escándalos en los medios sobre personas que violaban la cuarentena e infectaban a otros.

Calles vacías de Palermo durante la crisis de corona.

Sin embargo, me pareció que la mayoría de las personas alrededor mío sí se estaban quedando en sus casas. De hecho, muchos argentinos encuestados en abril apoyaban las medidas preventivas como la cuarentena, a pesar del desastre que eran para la economía y para los argentinos más vulnerables. Efectivamente, una proporción grande de las personas que vi en mis viajecitos afuera estaban en situación de calle, destacando cómo la crisis de corona estaba exacerbando desigualdad socioeconómica en el país.

Las únicas otras personas que ví afuera eran policías, repartidores en bicis y motos, personas con barbijos y a veces guantes con bolsas reutilizables, y personas paseando perros. Note que cada vez que salía, veía menos y menos personas totales afuera. Adicionalmente, vi un aumento general en medidas sanitarias, con más puestos de alcohol en gel y chequeos de temperatura en las entradas de farmacias y supermercados.

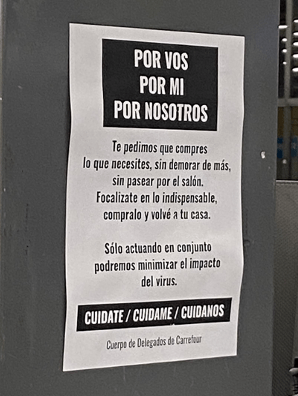

Distanciamiento social y otros protocolos nuevos en el supermercado Carrefour.

En general, apreciaba muchísimo mis mini-viajes afuera. Me ayudaban a sentirme menos atrapada en casa. Al mismo tiempo, hice todo lo posible para disfrutar de mi tiempo adentro. Aunque pasaba muchas horas todos los días en clases virtuales, también me mantenía ocupada con hobbies y otros proyectos. Me anoté en el programa voluntario “Mayores Cuidados” organizado por el gobierno de la Ciudad, pero nunca me emparejaron con nadie. En los días cuando me sentía muy encerrada, que eran casi todos los días, iba al balcón y leía o intentaba hacer yoga. Veía muchos de mis vecinos en sus propios balcones. Algunas noches, volvíamos todos afuera para aplaudir a los médicos, enfermeros, y otros trabajadores de salud. Otras noches, se escuchaba los ecos de cacerolazos en los cuales personas protestaban la excarcelación de presos, reclamaban que los políticos se bajen los sueldos, o por otras razones.

Mientras que Estados Unidos supera 1 millón de casos confirmados de coronavirus, Argentina tiene menos de cinco mil casos hasta el momento. Con el tiempo, se me hace menos y menos claro si tomé la decisión correcta al irme del país. Y en estos momentos en los cuales estoy leyendo las noticias más que nunca, me siento simultáneamente muy conectada y muy desconectada del resto del mundo.

Calles vacías de Palermo durante la crisis de corona.

More Student Views

Weapons of Mass Construction: Building a Puerto Rico for the People

I zip up my raincoat and turn on my headlamp as we tread along a damp trail in El Yunque National Rainforest, Puerto Rico.

Climbing the Tepozteco: Meditations on Mexico

English + Español

With sweat trickling down my forehead, I meditated on the question: What does motivation look like?

Cultivating Resilience in Puerto Rico: Harvesting Fields of Change

As a born and raised Puerto Rican, my journey has always been intertwined with my homeland’s vibrant hues and resilient spirit.