Skin Color and Educational Exclusion in Brazil

Affirmative-action programs in Brazilian higher education

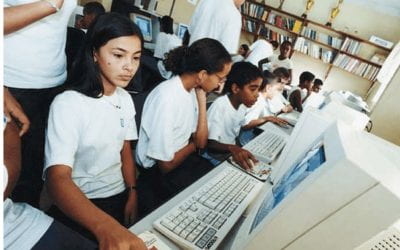

Questions of identity and race have recently given brazilians a lot to mull over. Photo by Cristina Costales

Worldwide, the black population in Brazil is second only to that in Nigeria. Brazil’s black citizens account for the largest number of people of the African Diaspora in the Americas. Historically, both within and outside its borders, Brazil has been described as a racial democracy, a society that avoided the state-sponsored segregation of South Africa and the U.S. South and where miscigenação among blacks, whites, and all other racial categories is highly celebrated. Yet, racial stratification does exist and the white population occupies a superior position. Blacks (pretos and pardos), on the other hand, have lived under a cumulative cycle of disadvantages, proving the country to be confronted with discriminatory and racist practices based on an individual’s race or skin color. In 2001, right after the Durban Conference on Racism and Xenophobia, the government officially acknowledged that there is racism in Brazil, making it clear that the concept of “racial democracy” does not reflect Brazilian reality. As a result, a form of affirmative action—quotas—was endorsed to address racial inequalities. Government sponsored programs were created, along with the implementation of quotas in various Ministries and a few public universities.

The pressure to implement affirmative action has stemmed from some sectors that have become increasingly aware of Brazil’s racial inequalities: the black movements, the academic community in the public universities, a few lonely voices within the leftist and center-leftist political parties, all of which stirred some polarizing views among public opinion. These sectors argue that the ideology promoted by Gilberto Freyre, who characterized racial relations in Brazil as democratic, has collapsed, and that a social reform focused on multiculturalism is indispensable in the modernization process of the Brazilian society.

In 2005, I began to collect data to examine the process of implementation of affirmative action through the quota system in three Brazilian public universities: Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), the Universidade de Brasilia (UnB) and Universidade do Estado da Bahia (UNEB). These universities reflect a broader concern with affirmative action policies that seek to achieve equality of educational opportunity in higher education. The three universities have been mobilizing different groups, social movements and non-governmental organizations based in Brazil and abroad, with the explicit support of the Brazilian government.

My main goal was to examine how the implementation of a system of quotas for Afro-descendents in the public system of higher education in Brazil could bring about changes in the way Brazilians deal with concepts such as social inclusion, reparations, diversity and “race” identity. My study focused on how the universities view the process of determining racial identity through a skin color categorization in the admissions process.

These three universities are among the first public institutions of higher education to adopt a form of affirmative action—quotas—for blacks in Brazil. In each case, proponents of affirmative action have highlighted that without race-sensitive policies it would be impossible to ensure a diverse student body. With that in mind, each one of these institutions created its own formula to guarantee the presence of minorities on their highly selective campuses.

I decided to focus on these three particular universities because of their very distinct profiles regarding the adoption of quotas and ways of proposing solutions for the problem of racial categorization. UERJ and UnB have encountered much publicity and controversy as well. The self-identification policy at UERJ paved the way to a series of frauds, detected when a great number of students applying to its programs claimed to be black when the university said they actually were not. The University of Brasilia has decided to take pictures of candidates who wanted to be included in the quota, establishing a panel of ”specialists” to decide who could be considered black. The Universidade do Estado da Bahia (UNEB) has adopted quotas only for students from public schools, following both a “class-based” criteria and the system of self-identification. With a very unique set of characteristics, the state of Bahia is the only one in Brazil where three fourths of the population is black. Quotas have been established at 40% and have left many wondering whether such a policy represents a measure for inclusion or exclusion for its population. The fact is that the institutional and regional variation between these universities might have consequences for the definition of who is “white” and who is “black.”

THE NATIONAL DEBATE OVER QUOTAS

In Brazil, the debate about affirmative action has been reduced to a debate about quotas and this has provoked lively exchanges in society and in the press. Quotas are said to be impossible to implement because of the difficulty of identifying who is black in Brazil. The deep cleavages in the aftermath of the adoption of quotas for Afro-descents in Brazil exposed a reality in which divergent viewpoints and perspectives surrounding policies that aimed at fostering equality of educational opportunity for the “disadvantaged.”Students provoked some heated debates on issues of access, equality, equity, exclusion, racism, discrimination, and the legitimacy of any form of race-based policy in the country. By challenging the foundation of Brazilian national identity that Edward Telles described as the one that sees Brazilians as one mixed people and where all different cultures and “races” have all contributed to the formation of the country, the quota system in higher education forced people to recognize differences in race and ethnicity and made the policy even more contentious.

Part of the reason behind this is that both proponents and opponents of affirmative action use the concepts of fairness and justice to defend their arguments, which makes it difficult to find a consensus. From higher education admissions to employment practices, affirmative action has the potential to affect everyone. Since its inception, affirmative action has been a widely debated topic. Throughout society, people have discussed the question of whether or not the policy fairly addresses inequalities that minorities may face. On one side are affirmative action supporters who argue that the policy should be maintained because it addresses discrimination in an equitable manner. On the other side, affirmative action opponents contend that it disproportionately considers minority interests over the majority. This controversy over affirmative action embodies the on-going difficulty of addressing racial inequality.

Elected officials have attempted to legislate the issue by passing constitutional amendments and laws. Brazilian lawmakers took action on the problem of racial prejudice for the first time after the United Nations Conference in Durban, South Africa, in 2001. Despite the government’s support of affirmative action in federal agencies and higher education, many questions continued to surround the issue, such as: does the policy provide an unfair advantage for minorities? Is affirmative action an important policy that helps close the economic gap between whites and blacks? In seeking answers to such vital questions I have observed that it would likely depend on whether or not one supports affirmative action. In general, arguments from the left tend to defend the use of affirmative action in higher education while those from the right argue against the policy. By looking at arguments from the left and the right, one can see why affirmative action in higher education remains such a divisive policy.

Borrowing from a functionalist point of view, opponents to affirmative action argue that selection of individuals in higher education should be based on merit and talent. This view is aligned with a functionalist stance that believes that certain needs in society can only be served by the special talents of a relatively few people. Supporters of affirmative action, on the other hand, assert that unequal social and economic conditions play an important and decisive role in inhibiting minority students’ access to higher education.

The latter view aligns with the conflict theorists’ belief that schools serve the dominant privileged class by providing for the social reproduction of the economic and political status quo in a way that gives the illusion of opportunity. Moreover, schools contribute to the continuation of the system of domination by the privileged class.

Afro-Brazilians are faced with a series of complex problems. Statistics show that blacks and browns comprise the majority of those who are at the bottom of the socio-economic scale. Poverty and racial concentration are mutually reinforcing and cumulative, leading directly to the creation of underclass communities typified by high rates of educational failure, among other factors. Essentially, this type of social condition creates a vicious cycle that makes it difficult to escape (Henales and Edwards, 2000). This disproportionate reality provides evidence to affirmative action advocates that social and economic conditions are the equivalent to racial inequality because the differences in opportunities are divided by race. Supporters who use this argument advocate that affirmative action in higher education is needed to increase educational opportunities so that minorities have the ability to improve their social and economic conditions.

THE DYNAMICS OF RACE IN BRAZIL

An analysis of issues of race and ethnicity in Brazil demonstrates very strongly that ethnic identity is a social construction that differs from context to context. As we agree that racial and ethnic identities are considered a resource of power, some scholars have shown that depending on specific circumstances, people tend to mobilize certain social identities because they might deem them more rewarding (Sansone, 2003). The main color line in Brazil has always been between whites and non-whites. According to the 2000 census, the population in Brazil is divided among blacks, browns and whites (6.2%, 38.4%, and 53.7%, respectively) based on color or race self-classification. The distribution among these groups has changed through time due to high rates of miscegenation and intermarriage or simply by change in self-classification, making racial boundaries much more blurred than those of countries like the United States or South Africa. Since the end of slavery in 1888, all state policies have been color-blind—Brazil never had any equivalent to apartheid or Jim Crow segregation—and educational systems have never used race as a criterion of exclusion. Certainly, discrimination does exist, although the “myth of racial democracy” can be prevalent in popular culture and some academic works. Blacks in Brazil are overrepresented among the less privileged groups in society and underrepresented in professional occupations and in higher education.

In most Brazilian racial relation studies blacks (pretos) and browns (pardos) are joined and classified as blacks (negros). This is justified by the similar socioeconomic characteristics of these two groups, especially when compared to whites. In addition, there are small numbers of indigenous groups and Asians in Brazil, which together represent less than one percent of the population. Although they are not discussed in this article, it is important to note that indigenous groups are included in racial quotas in certain states.

Hopefully, the discussion over quotas regarding race, ethnicity, and skin color in Brazil will be a never-ending story. Through this debate we gain a deeper understanding about the impact of race in Brazilian citizens’ conceptualization of their own identity and their level of engagement in the affirmative action process, as well as their expectations regarding the role of the state in guaranteeing social equality through education. We are also able to assess how individuals and institutions of higher education isolate the number of different identities and the diverse notions of ethnicity and race that exist in Brazil for the purpose of entering the university.

Historically, although the university system has never officially excluded blacks, general access to higher education has always been highly elitist. In the past decade, the higher education system has expanded through the private system, keeping the prestigious public universities (free of tuition, federal and state institutions) very selective and elitist. Ironically, even with the lack of a segregated system (or the inexistence of historically black universities), the underrepresentation of black university graduates is higher in Brazil than in countries like the United States and South Africa. This has been the main argument for pushing race-targeted affirmative action in Brazilian public universities.

These new race-based policies in the country have emphasized a new understanding of how race and ethnicity are constructed and they go to the core of a discussion that revolves around the question of being “black” in Brazil.

Spring 2007, Volume VI, Number 3

Paulo Sergio Da Silva is a doctoral candidate in the International Education Development program at Teachers College, Columbia University, where he came as a Fulbright fellow. With a grant by the Institute of Latin America Studies at SIPA he started collecting data and examining the process of implementation of quotas and its consequences regarding granting access and guaranteeing the permanence of Afro-Brazilians in the country’s public colleges and universities. He is part of the committee and an active member of the Association of Latin American Scholars (ALAS), a student organization at Teachers College.

Related Articles

Becoming Brazuca? A Tale of Two Teens

Prior to arriving in the boston area almost five years ago, I had heard anecdotally that a significant Brazilian immigrant population had been arriving en masse to the region since…

Education: The Role of the Private Sector

I remember walking into the room for my last interview for the scholarship from Fundação Estudar. As soon as the other five candidates and I found our assigned seats, we realized that our…

Biomedical Spending

I have traveled a lot in recent months, from Phoenix and Salt Lake City to Budapest and Amsterdam. I even purchased a world map, one of those for putting up on your wall…