Social Responsibility in Latin America

Effective involvement in social issues is essential to business, both in the United States and Latin America. In recent years, most-although certainly not everyone-increasingly agree that business concerns should become more “socially conscious.”

Yet there is little agreement on what this means. Confusion is inherent in the term itself: social responsibility, corporate community involvement, corporate citizenship and social investment are only some of the terms used to shed light on behaviors embarked upon that go beyond conventional strategic and profit objectives. “Social responsibility” encompasses a wide variety of attitudes and behaviors within corporations as well as between the corporation and its external stakeholders. Let’s examine these terms more closely with particular emphasis on Latin America.

First, it’s interesting to note that not everyone agrees to whether corporations should think beyond the profit motive at all! Milton Friedman argues rather convincingly that the business of business is to maximize profit, leaving all other activities aside. While executives are certainly welcome to engage in community activities as volunteers or as donors, these activities should be performed outside of the workplace.

However, the predominant argument, perhaps more convincingly, suggests that corporate involvement is in fact good business because it supports and improves core business functions. Tying activities directly to perceived benefits is difficult however–causal relationship can seldom be established.

As competition increases, as technological advances continue to proliferate, and as businesses merge, it becomes more important to examine these concepts of corporate responsibility and to think strategically and systematically about effective community involvement.

Let’s revisit these definitions again and examine them, using both a Latin American and a U.S. lens. Examples abound in this country. Timberland continues to work closely with CityYear, a national youth building organization and has continued and in fact deepened the relationship during a difficult business downturn. Cisco initiated its Corporate Fellows Program which allows some of its highly skilled technology staff to work for a year with a non-profit organization at reduced salary. Monsanto works closely with small farmers to help them increase production; at the same time, the company benefited by learning how best to service this new and large market of farmer-consumers. While U.S. corporations are generally convinced about some tangible benefits, the intriguing question remains whether these efforts are applicable to Latin America. There appears to be a widespread trend for businesspeople in Latin America to keep their philanthropic activity distinct and separate from their core business. At the same time, data suggest that communities in Latin America tend to view large corporations with some element of distrust; therefore, effective corporate involvement might have a positive impact. This artificial separation between what an executive gives on his own and what the corporation does makes it difficult for corporations in Latin America to assess community need, develop plans to strategically address these needs and learn from these ongoing associations. This type of assessment and planning have been key factors for successful and effective collaboration in the United States. This artificial separation also has the unfortunate effect of limiting existing business initiatives. If these efforts are not accepted as strategically important and considered to be superfluous or outside of “normal” business activities, then they are particularly vulnerable to economic down cycles as well as to changes in leadership.

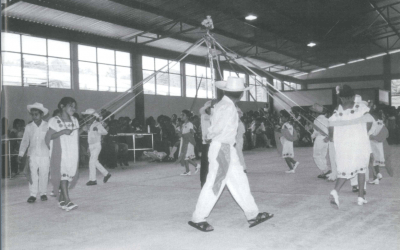

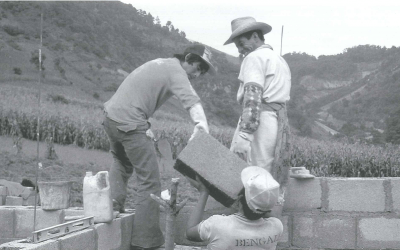

Perhaps it might be helpful to use a simple framework that defines some of the terms presented and uses examples for each. If one thinks of a continuum (see accompanying graphic), on the far left we have corporate social awareness. A corporation has gradually come to understand that its stakeholders go beyond its vendors and customers, that they include employees, families of employees and the community at large. This awareness is by no means automatic and a range of organizations, such as Forum Empresa, a web-based organization for social responsibility in the Americas, and the Abrinq Foundation, a large Brazilian foundation for the improvement of children’s lives of are trying to mobilize corporations around issues of social justice. Moving towards the right, we have corporate social responsibility, initiatives that link business decisions to ethical values and respect for people, communities and the environment. The range of these activities generally exceeds commercial and public expectations. Examples of this might be Natura Cosmeticos in Brazil, recognized as a leader for its commitment to the communities in which it operates, supporting human rights locally. Empresas Interamericana, in Chile is another example, providing ten monthly grants for dental services to impoverished women. Moving again towards the right, we have corporate social involvement, describing corporate activities that make these beliefs concrete, moving beyond the advocacy role, such as forming partnerships with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or acting independently to make changes. A corporation might encourage employees to become more socially active, such as Shell in Chile, where employees manage initiatives to build low income housing. These efforts however, are separate from the core activities of the company. Finally, on the far right, we have corporate citizenship, where social responsibility has become part of business norms and strategy. At this point decisions need to be made about the locus of these activities. Where should they be housed? Who should be in charge? How closely should activities be to corporate strategy? How will careers be affected by attending to this area? Issues of a target audience need to be addressed as well. While U.S. companies have taken on seemingly intractable social problems such as urban schools and employing welfare mothers, traditionally Latin American philanthropy and corporate interests have most often provided support for activities benefiting middle and upper income groups such as fine arts and cultural awards. In Brazil, this situation has begun to change, with many corporations newly involved in activities that benefit the lives of children including housing and education.

Data suggest that Latin American initiatives tend to cluster towards the left of the continuum. Clearly, examples do exist of the corporate sector’s proactive transformational activities. One such example is Pollos Ariztía, a large chicken producer near Santiago, Chile, where company president Manuel Ariztía has taken a lead role in improving education including professional teacher development. Initially a one-person effort, this initiative is now reflected throughout the company and is an intriguing example of a corporate-NGO-municipal collaboration that has gone beyond “philanthropy” to real corporate citizenship.

In general, however, there appears to be more intermediation in Latin America. Foundations or NGOs are often established to encourage corporations to begin moving along the continuum, by raising awareness about poverty or human rights and providing opportunities for more corporate involvement. Numerous examples exist; in Mexico the Centro Méxicano para la Filantropía showcases companies that have a real concern for the lives of their workers, and in El Salvador, eighty two founding members of a new organization, including individuals, companies and foundations have come together to encourage business philanthropy. These intermediaries are playing a key role, raising difficult issues, building community and perhaps changing expectations about possibilities for further involvement.

While the number of companies playing important roles on each point of the continuum is quite different in Latin America, compared to the United States, corporations in both regions will be driven by similar mandates during the next decade. Customers will continue to be drawn to brands and companies considered to have good reputations in areas of social concern. Sophisticated ways of measuring the economic value of these activities will continue to be developed, making it easier for senior managers to introduce these activities as part of the corporate “core” and not “add-ons.”Companies in both regions will find ways to develop new products, test new technologies and enter new markets while also being responsive to external needs and demands. IBM and its initiative on Reinventing Education and Bell Atlantic’s work on wiring a school are good examples of these benefits. Additionally, as more courses become available in business schools in the area of social impact management and as the media plays a stronger role in disseminating new initiatives and successful ventures yet more corporations will move towards the right of the chart. Finally, as we move towards a more global economy, the value of brand image and reputation will become more valued assets. A strong position on the right side of the continuum, in the area of corporate citizenship, whereby employees as well as consumers share concern for social issues and are willing to build long term partnerships around these concerns, will be viewed as beneficial for corporations. Traditional philanthropy will become less important than strategically determined initiatives that will change priorities and improve lives.

Spring 2002, Volume I, Number 3

Diana Barrett teaches in the Social Enterprise Initiative at Harvard Business School and works with a range of philanthropic organizations in the United States, as well as in Latin America.

Related Articles

New directions in Latin American

It was in Amsterdam in the winter of 1978 when I first came into contact with an animal that would later become a monster with multiple heads. It was a time of exile and hundreds of people were …

Latin American Philanthropy in Changing Times

When I first moved to Latin America fresh out of college in 1981, I was filled with ideals about working for human rights and social justice, like many of my generation. If anyone had suggested …

The Societies Of St. Vincent De Paul In Mexico

The Mexican volunteers established institutions such as schools, shelters, soup kitchens, lending libraries, and credit unions for the urban poor. They pioneered adult education and helped …