Society and Education

Latin America’s Challenge for the Twenty-First Century

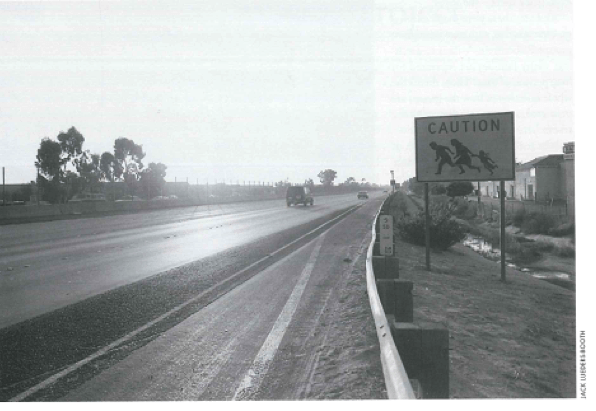

Education: children at the crossroads, a sign at the US Mexican border.

As a member of UNESCO’s International Commission on Education for the Twenty-First Century, I’ve come to realize that education is about much more than books. It’s about the “four pillars of learning” directly to the major challenges facing education: Learning to live together in this new interrelated world, with its massive migrations and ethnic conflicts;Learning to know, the development of students’ competence in interpreting and explaining facts, of rational thinking in order to acquire not only knowledge, but also wisdom, about the world we live in; learning to do, acquiring the competence to face changing technologies and shifting labor markets, and learning to be, developing one’s full potential as a free individual and as a responsible member of a larger society.

Achieving this goal involves building partnerships, whether those partnerships are with businesses, labor unions, or rural cooperatives. Above all, it means building effective links with local communities.

Building partnerships for quality improvement in education requires more than an administrative decision at some governmental level. It involves research and dialogue with potential partners about the different needs and possibilities of everyone involved. For example, in most Latin American countries rural schools lag well behind urban schools in every respect, and among the former, schools in areas with indigenous populations are even less better off.

Inadequate resources and lack of trained teachers are, of course, factors, but I consider inadequate understanding by educational officials of the social and cultural needs of the local communities to be the primary problem. Although serious efforts are underway in a number of countries to develop a truly bilingual and intercultural education for indigenous children, only very few well-trained teachers speak the indigenous languages. Local officials or even teachers coming from other areas quite often hold indigenous traditions in contempt. For decades, official educational policy in Latin American countries aimed to assimilate the indigenous population and disdained their languages and cultures. Consequently, educational levels and outcomes among indigenous children were poor, whereas school desertion rates were high. (As a matter of fact, a similar situation prevails among Hispanic children in many parts of the United States).

In situations such as these, partnerships with the local community mandate knowledge of and respect for local culture and vernacular languages. Before imposing a new curriculum or educational agenda on rural school systems, education officials need to establish trust and mutual respect with local communities. This takes time and cultural sensitivity, something which bureaucrats on the run do not always possess in sufficient quantity. But beyond that, it sometimes means redefining the concept of the nation and the national culture, an issue that elected or appointed officials are not always eager to take on.

The Principal Project of Education

In 1979 the Ministers of Education of Latin America and the Caribbean established the Principal Project of Education (PPE), a major coordinated regional effort. The Project aimed to achieve universal school access and to eliminate illiteracy by the end of the century. It also sought to improve educational systems’ quality and efficiency through adequate reforms. At the end of the nineties, the first two objectives appear to have been achieved, whereas there is still a way to go regarding the improvement of quality and efficiency of education systems.

In Latin America, as in other parts of the so-called “developing world”, international cooperation can play a significant role in educational development. The Commission identifies a number of common themes in international cooperation, such as the need to see education systems as a whole and to conceive reform as a democratic, consultative process related to an overall social policy.

The North-South imbalance must be offset with increasing North-South and South-South cooperation. From debt-for-education swaps, to regional exchanges of teachers, researchers and students, to the establishment of regional research and training centers (as the United Nations University has done), to facilitating poorer countries’ access to the new information technologies, to the building-up of basic educational infrastructure and teaching capacity: the possibilities for international cooperation in education are vast. The Commission believes such new partnerships can be built with UNESCO’s involvement and among member states directly.

International cooperation in education in the region takes many forms. The Inter-American Development Bank financed 32 educational projects for a total of $ 1.7 billion during 1994 and 1995 alone. Many of these projects involve educational reform efforts, including administrative decentralization at local levels, increasing autonomy of schools and parental involvement and higher incentives for teachers, as well as more traditional aspects of educational reform such as curriculum development.

The World Bank, a major partner of Latin American efforts to improve education, has increased its investments in education from less than $200 million before 1991, to more than $800 million in recent years, which represents nearly 14% of the total regional budget for education. Eighty per cent of World Bank loans go to basic education, a policy reflecting priorities determined by the region’s countries. A major concern is to raise the average of 5.2 years of schooling of the population-two years lower than the average in the countries of East Asia; as well as to improve academic efficiency, which is also lower in Latin America than in other areas with similar income levels. The World Bank has agreed to support such educational reforms as extending pre-school education and improving the quality of basic resources in schools, from textbooks to teacher training.

Another regional effort is coordinated by the Organization of American States (OAS), with particular emphasis on basic education, education for work, and in 12 countries, middle and higher education. Participating states have committed almost $15 million to these three regional cooperative projects. A preliminary evaluation of the projects concludes that their results have been positive, pending a more careful study of their impact on the improvement of the quality and efficiency of education.

The Organization of Iberoamerican States for Education, Science and Culture (OEI) is yet another regional effort (including Spain and Portugal) to help improve education. It is involved in prospective studies, the teaching of science and mathematics, educational research, the building of data bases and publications.

UNESCO’s Principal Project of Education recognizes the important role of international cooperation in achieving its strategic objectives. Between 1990 and 1994 external financial cooperation for educational purposes reached a level of more than $ 1 billion per year, a small fraction of total need, but a significant contribution to flexible expenditures for educational innovation and the improvement of quality.

One example of community partnerships is EDUCO in El Salvador. In 1991, the Salvadoran government decided to improve rural education by transferring funds from the Ministry of Education and delegating management of new rural preschools and primary schools to parents and community groups through a special Program called EDUCO. A locally elected Community Association for Basic Education (ACE), whose members are drawn from the parents of the school’s students, hires and fires teachers and closely monitors their attendance and performance, while ensuring direct feedback about pupils’ progress. It also receives funds to buy limited school supplies. The role of the Ministry of Education’s role is to help organize the ACEs and to train teachers and supervise their performance, The ministry also establishes the criteria for teacher selection: all teachers in EDUCO must be college graduates. By 1992 the program had expanded to 958 schools in all fourteen departments of the country, and over 45,000 pupils, 10% of all rural students in grades one to three were enrolled in it.

The program has faced opposition, particularly from teacher unions and leaders in the zones formerly in conflict, during El Salvador’s twelve-year long civil war which ended in 1989, where it is perceived as a strategy of political co-optation. In these areas an alternative form of teaching emerged during the war– the popular teachers (maestros populares), supported by the political opposition. These now see EDUCO as a strategy of the central state to neutralize the network of popular teachers who identified with the opposition during the war. Teachers unions also opposed being hired by community associations, which fragmented the relationship of the trade union with a single employer: the education ministry.

An evaluation of teacher performance indicates that teachers in community-managed schools use more innovative practices and expose their students to more group work and pedagogical games than teachers in traditional schools. However, many rural communities were not able to provide a local college graduate as teacher, thus requiring teachers to come in from the outside, sometimes having to travel long distances.

Harvard’s Fernando Reimers found in a 1997 study that standardized tests and evaluations showed that EDUCO has not made a difference in the number of class days or in the length of instruction students receive, findings inconsistent with the expected effect of the program. The study concludes that while students in EDUCO schools perform at levels comparable to those of students in other schools, there is no indication that this innovation has substantially increased school quality, internal efficiency, or even community participation. EDUCO shows that school autonomy and local participation are not panaceas, and require a long time to mature and produce their expected beneficial effects.

Communities are the building-blocks of a healthy society; in today’s multicultural and multiethnic world, it is at the community level that tensions, frictions and uncertainties must be resolved. Educational systems will flounder without community support, and they will flourish with community involvement. A successful educational system is the one that is able to draw upon the strengths and resources of the underlying community and it will, in turn, contribute to that community’s vitality. This is a window of opportunity for the educational systems of the twenty-first century. The four pillars of learning, referred to in the Commission’s report, must be solidly anchored in the life of the community, a task in which many social actors can cooperate. I believe the challenge is to find models in which these partnerships can function effectively.

Teachers as Partners

Dialogue between officials and teachers is crucial to this relationship. Teachers often feel that they are not involved in major decisions concerning educational programs. Their view of education seen from the classroom may be quite different from that of an educational planner negotiating budget approvals in ministerial offices. Educational needs do not always coincide with political imperatives. A case in point: in the middle ’70s, responding to criticisms about the content of the official primary school textbooks used in the country, the President of Mexico decided to create a task force of social and natural scientists and other academics to rewrite the manuals. This ambitious objective had to be carried out in a few months, due to a specific political timetable. The Commission set about its task with great enthusiasm, and the books were published on time and distributed to millions of elementary school students at the beginning of the new school year. There had been no time to test them in practice, evaluate their effectiveness and correct their errors and defects. School teachers, who had hardly been informed of these curricular changes, were asked to use the new textbooks in class immediately. They became the program’s strongest critics, and demanded a return to the earlier system. Within a few years, under a new government administration, the books were scrapped and the old system was restored (still in place twenty years afterwards). The Regional Committee of the Principal Project in the Field of Education in Latin America and the Caribbean, supported by UNESCO, considers that the first and foremost challenge in order to overcome the key causes of low quality education in the region, is to create public support for personalized and group learning. Once this is achieved, other challenges can also be met. But how is public support created? Will the ministries take the initiative? The teachers unions? What role will there be for the media? Do national parliaments have a role to play?

Educational systems cannot flourish and achieve their main objective in society in isolation from other sectors. How to develop constructive dialogue with these other sectors and their various actors (local communities, social interest organizations, economic agents, ethnic and cultural groups) is one of the major challenges as we enter the twenty-first century. The Commission has high hopes that these challenges will be met successfully. Jacques Delors, the Commission’s president, affirms that there is “every reason to place renewed emphasis on the moral and cultural dimension of education, enabling each person to grasp the individuality of other people and to understand the world’s erratic progression towards a certain unity…” In this context, cooperation and dialogue are essential, because, as Delors points out, “..after so many failures and so much waste, experience militates in favor of partnership, [and] globalization makes it inescapable…”

Spring 1999

Rodolfo Stavenhagen is a research professor at El Colegio de Mexico and a member of the International Commission on Education for the twenty-first century, UNESCO. He has been named the Robert F Kennedy visiting professor of Latin American studies at Harvard University for the year 2000. He will teach in the Harvard anthropology department, his article is based on his presentation at the biennial meeting of the association for the development of education in Africa (ADEA) Dakar, Senegal, October 1997.

Related Articles

Editor’s Notes: Booknotes

On March 10, 1999, President Clinton apologized to the people of Guatemala for the support provided by the U.S. government to that country’s repressive military-backed governments…

Noel McGinn’s Life of Learning

Noel McGinn, professor of education, had a normal American childhood in a small, sleepy town directly south of Miami-but 1200 miles south and across the Caribbean, in the Panama Canal Zone…

Latino Families and the Educational Dream

Insisting that we do our interview in English, Ricardo Robles reluctantly recalls the dreams he had for his children when first arriving nine years ago to the U.S. from Zacatecas, Mexico.” They…