Suffering That is “Not Appropriate at All”

A Harvard-Haiti Lament

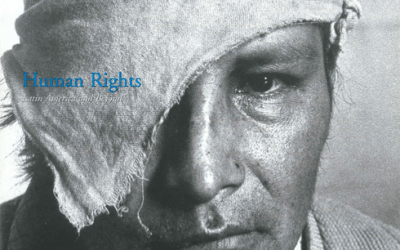

Lorieze: a special kind of human rights issue. Photo by David Walton.

A few weeks ago, a few friends and co-workers from Partners In Health, a small Harvard-affiliated organization concerned with lessening health disparities, put together a photographic exhibit called “Structural Violence: A View From Below.” Most of the pictures were taken in Latin America. The response to the exhibit was very positive, judging from comments in the guest book. Some of these photographs were of my own patients, and all of them were taken by my co-workers and students. Others chose the photographs and the title of the exhibit; others did the hard work of hanging them in the Holyoke Arcade and designing and mailing a simple and elegant invitation. I was either in Haiti or on medical leave after injuring my leg in a fall down a Haitian hillside. I’m ashamed to confess right here that I have not yet seen the exhibit at the time of writing. It is now hanging in a Harvard student residence, Eliot House, the Cambridge home to which I return in a few days.

When I see the exhibit, however, one photograph will have been removed at the request of a visitor who wrote in the guest book “not appropriate at all.” This verdict was underlined twice and also telephoned to the building administration as a formal complaint. To avoid giving offense to this visitor and—presumably—others similarly affected, the photography show’s organizers took the picture down. The offending photo is the one right on this page: an informal portrait, taken by one of her doctors in the course of a home visit, of a Haitian woman struggling to survive both breast cancer and poverty.

Like most women living in dire poverty, Lorieze had been diagnosed tardily. In her case, the tumor had already consumed much of her breast. She had a mastectomy in the Partners In Health hospital based in Cange, here in central Haiti. Afterwards, another colleague carried some of the tissue to Boston in order to find out if Lorieze might benefit from chemotherapy. She would and she did. Surgery and chemotherapy—vanishingly rare in rural Haiti and available, to my knowledge, only in our hospital—have given Lorieze a second lease on life. The photo was taken (during a follow-up home visit) with her blessing, as were the other photographs in the display. Indeed, many of our patients here have asked that their pictures be taken; many have asked for copies of their images.

What about this photograph, I wonder, prompts such extreme reactions? It can’t just be the depiction of a breast (a spectacle to which the general public is no doubt as inured as I, a medical professional). Is it the suggestion of disease, surgery, pain, and other things we prefer not to think about? Or is it the deeper history that the photograph expresses, if we only know how to decipher it?

I did some preliminary checking up on Lorieze. She was doing much better, according to her doctors in Lascahobas, about an hour and a half from here by Jeep. But the disease will still likely kill her. Our interventions were delivered with technical competence and hope and a great deal of love. But nothing will change the fact that this woman wandered around Haiti’s towns for more than a year, looking for someone to diagnose and treat her illness, and found nobody. Breast cancer is awful anywhere. So are AIDS, other malignancies, drug-resistant tuberculosis, and a host of other diseases that afflict the poor disproportionately. But once afflicted, the victims of structural violence are in a very different situation from others diagnosed with the same illnesses. As in Haiti, the poor everywhere rarely have access to even the most mediocre medical care. Partners In Health’s mission is to lessen inequalities of access to care. So this image—of a rural Haitian woman with only one breast—addresses a special kind of human rights issue: the right to health care.

Surely the right to health care, like other social and economic rights, is important. Many of the people Partners In Health is privileged to serve in Haiti, Peru, Roxbury, and Siberia have told us in no uncertain terms that food, housing, jobs, and shelter—freedom from want—are the rights they care most about. Yet these are not the rights discussed often in the affluent world, where civil and political rights have long dominated the rights agenda, itself decidedly flabby in many of the wealthiest countries. But some people who don’t think much about the right to food or housing are sympathetic to the right to health care, since almost anyone, rich or poor, can imagine what it would be like to be sick and without medical care. If the right to health care is so basic, why, exactly, would a photograph rich with lessons for the affluent rankle or offend?

I heard of the photo incident while here in Haiti, where priorities of a completely different order prevail. Here, an hour and a half from Miami, civil and political rights are important but the daily struggle is mostly for survival. And although Haitians do not enjoy the right to health care, they do, in my experience, have systematic and comprehensive notions about such rights. Many are articulate in asserting tout moun se moun—every one is human. The currency of this proverb is striking in Haiti, the very land in which human rights have so long been denied. A rich human rights culture is now emerging, but it is coming from the poor. The subtext of this saying, tout moun se moun, is usually that poor people deserve access to food, school, housing, and medical services. I hear this sort of commentary almost every day in our clinic in central Haiti.

The political and moral culture of affluent universities such as Harvard seems, at times, not to share a planet with rural Haiti. Major campus struggles have sometimes concerned issues of representation. As a graduate student in anthropology, I heard frequent discussion of who has the right to take a photograph and display it. Of course academics have written tomes on photography, and anthropologists have a strange obsession with representation (in both artistic and political senses). But the Partners In Health photographs were not displayed to exploit the suffering of others but to bring people whose lives are different and far less difficult—that is, people like us—into a movement: a human rights movement in which people connected to a research university would have a great deal to offer.

Representation is inherently controversial. I can easily agree with the proposition that the photographer (even the physician-photographer) stands, through luck, privilege, education, and social standing, in an unequal relationship to the person photographed. But the point of the picture is not to reinforce that inequality. It is to testify to deep questions of history and political economy. A look at a photograph of a woman who has received far more medical care than more than 95% of most Haitian women with breast cancer, but far less than most Northern Hemisphere women with breast cancer, offers us all a chance to think about health care as a right. Dismissing such images as “not at all appropriate” is an excellent way of stopping that conversation and of undermining serious studies of why, for example, the likeliest outcome for a woman in rural Haiti so afflicted would be death without even a diagnosis, much less therapy.

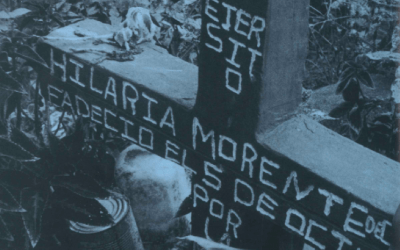

The anonymous visitor’s expression of anger cannot readily be glossed as “political correctness”—the blanket claim, often from conservative corners, that we should not place such images in public spaces. The comment in the guest book speaks, I believe, to a very different malady: a desire to avert our gaze from things that should make us uncomfortable. But regardless of what motivated the objection—after all, personal experience is undeniably valid as such, regardless of provenance—the images chosen were meant to afford us a chance to reflect on the lives of those assailed by both poverty and disease. So too should this second photograph, of a woman and her sleeping baby, make us begin to wonder why it should be so difficult for a young woman to keep her child alive. And why she should fail in her efforts, as she did, again because care came too late.

Of course we should also try, as an exercise, to approach this peremptory comment—“not at all appropriate”—with a hermeneutic of generosity. There is first, as I have said, the universal validity of personal experience. An announcement of discomfort can never be dismissed. But the Partners In Health photo exhibit was not about suffering in Cambridge or Boston, least of all about the suffering that viewing photographs might cause in Harvard-affiliated passersby. It was not shock art, not pornography, not a freak show; it was a report on the suffering of others. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if the comment was meant to tell us that it is “not at all appropriate” that some die of treatable diseases while others are spared that risk? That it is not appropriate that such exhibits, which might awaken the minds and passions of the students and faculty of a great university, do not occur more often?

Reflecting on this matter in Haiti, before I had even seen the photograph, led me to wish devoutly that such images would inspire solidarity and empathy, regardless of the viewers’ personal experiences. Because without such sentiments, we and our children will live in a world divided in an increasingly violent fashion between haves and have-nots.

If we’re going to talk about propriety, we might as well ask the hardest questions. Should poor people have a right to health care? Should the hungry be able to eat? Should there be a right to life? The photographic exhibition went under the title, “structural violence” because it sought to remind those who do not live in poverty just how violent it is to die of AIDS or hunger or breast cancer. When linked to other forms of analysis (in the case of the photographic exhibit, to books and articles and seminars—the traditional products of a university) these photographs do not simply move people to pity or empathy or indignation, useful though those feelings are. The photographs are also meant to take us beyond superficial analyses of deep ills. When health services are for sale and the destitute are not, by definition, capable buyers, what happens to them? Some have said that the term “patient” is demeaning, and there’s a movement afoot in the United States to call the afflicted “clients.” What a slick ruse this is. It’s a subtle part of the commercialization of medical care. When we read on the walls of businesses that “the client is king,” the client is a customer. Someone who pays for services. And this means, of course, that the services in question are defined as commodities, not as rights.

Lest I seem to be going astray, allow me to argue that the commodification of medical care is one of the biggest human rights issues facing the “modern” world today. Why use quotation marks around “modern”? Scare quotes are typically a craven ploy, but I use them here because the woman whose picture offended the viewer, though undeniably our contemporary, lives in a low-medieval hut, with a dirt floor and a thatch roof. Modern health care is available, for a price, in the private clinics of the city, but she received it for free in a rural squatter settlement only after a long time spent knocking fruitlessly on the doors of those modern clinics as a client without money. She was effectively locked out of the modern world with all its shiny laboratories and amazing medications until she wandered into our clinic and hospital.

The experience of a Haitian woman dying with breast cancer, her death delayed by desperate but effective measures, offers lessons about structural violence, itself an effect of the dizzying social inequalities spanned by our lives and work.

Now for disclaimers. Not out of cowardice, I hope, although I am also pained by the negative response written in the guest book.

The offending photograph was removed immediately and I learned that some of those who organized the exhibit were glad to take it down. But that action, comforting as it may have been in Cambridge, did not make this woman’s cancer go away.

I was not involved in the decisions to place or remove the photograph, but sitting here in Haiti, the matter pains me. It pains my colleague who took the photograph (“Do you think I did something wrong?”) as it might the surgeon who had insisted on providing, free of charge, the services. It would likely pain all of those involved in the transnational process of pathologic diagnosis and chemotherapy. These are people who believe they are fighting for the right to health care, as the patients, long denied this right, are quick to agree.

I decided to call the photographer, Dr. David Walton, from Haiti. This is his fifth year coming to Haiti. A recent graduate of Harvard Medical School, he could be paged through the operator at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. After a few minutes, his voice came on the line. He reminded me that he had not made the selection of photographs; he had merely offered up his vast trove of beautiful, often disturbing images (some of which have appeared in past issues of ReVista). Walton and others had worked hard to obtain care for this woman, and knew that his picture of her had been removed from the exhibit. The telephone connection was fuzzy, but I sensed that he felt strongly about the issue: “What is the photograph about if not the violence visited upon poor women, every day? What was the photograph about if not access to care?” He asked me if I thought that many rural Haitian women had received care for breast cancer. I replied that she was one of the few women ever to receive even palliative care for that disease, even though we have no data to suggest that breast cancer is all that rare in Haiti. (As readers will know, breast cancer is a ranking malignancy in the United States, where ribbons and marathons mark a broad and welcome societal concern with its diagnosis and treatment.)

Two weeks later—which is to say, today—I sent an electronic message to Walton. Now he was back in Haiti. Would he send me a paragraph about the photograph and what it meant to him to learn that his photograph had offended people in Cambridge? This is what he wrote:

“There are naysayers that would assert that treating breast cancer is impossible in rural Haiti. But we felt it was not only possible but absolutely necessary. Why should Lorieze be denied a chance at life because of her economic status? She needed a surgeon, so we found one. She needed a pathologist, so we carried the specimen to the States. She needed input from an oncologist, so we asked one of our Brigham colleagues to consult on the case. She needed chemotherapy, so we had some donated and brought it to Haiti. She had a radical mastectomy and four rounds of chemotherapy, all of which were provided free of charge. If she had to pay, she would never have received this care. Lorieze is a rural Haitian peasant farmer with three kids. Her husband left her several years ago, and she is the only provider for her children. Her death would have been more than catastrophic for her children, because such an event would leave them without anyone at all to care for them.

“The equation was simple: treatable breast cancer must be treated, especially in resource-poor settings, where the stakes are even higher and the consequences of losing a parent include, often enough, death for those left behind. I have seen it happen to AIDS orphans. The variables included surgery, chemotherapy, and input from our colleagues in the States. The outcome of this particular equation has been, I believe, a success. To date, Lorieze is doing extremely well. She did not have any major adverse reactions to the chemotherapy and she does not show signs of metastasis or recurrence. She has returned to her daily activities and to caring for her children.

“How did I feel when I heard the photo was taken down? I wasn’t really surprised. But knowing the details of this story, I felt a bit deflated. Not about my photo, mind you. Rather that despite the success of the whole endeavor in a place this poor, the photo, which shows Lorieze at her home, succeeded in offending at least one viewer. That the photo was taken down prematurely strikes me as an unsurprising reflection of our society and our priorities. Placing the sensibilities of viewers over the lives of others is a distortion of one of the most basic values that we all hold dear: the preservation of human life.”

I met Lorieze during her stay in our hospital. She told me she was grateful to have ended up in here and grateful for the efforts of our Cuban surgeon. Since she was slated for chemotherapy, I spoke with her and learned that, unsurprisingly, she’d never known anyone who’d had chemotherapy. Cancer care is almost unknown among the world’s bottom billion, and Lorieze sits on a rung very close to the bottom of that social category.

All those involved in her care agree that it is “not at all appropriate” that only a tiny fraction of the afflicted have access to proper medical care. We join our voices to those of our patients, who, not having visas to come to the United States, cannot be “empowered” to come and tell their stories in Cambridge and so shake our complacency.

A modern research university, and especially one as wealthy and powerful as ours, has certain obligations to the rest of the world. From the days of muscular missionary Christianity to the post-post modern moment, this question—what does the university owe the world?—has always been fraught. But few would say that the answer to this question is “Nothing.” Some answers quiver with scarcely-masked neocolonial ambitions; others seem paralyzed by a weary cynicism fanned by relativism and certain recent academic fashions. No good answer to the question is forthcoming as long as those strolling the groves of academe can neither understand nor “represent” the struggles of people facing the poverty and disease that luckier people are spared.

Are photographs of awful suffering “not at all appropriate” because they break down boundaries erected in order to keep misery out of our grove? I refer not to the misery of breast cancer, which causes much suffering in the United States. I refer to the noxious synergy between sickness and poverty in a world in which health care is not a right but rather a commodity, an unattainable one at that. Are disturbing images of ongoing suffering “inappropriate” because they undermine facile and fashionable notions of “empowerment”—facile because the concept lacks any meaning if not linked to social and economic rights, including the right to health? Are such photographs disturbing because they do not depict “clients” but people who really are both destitute and sick, and would be so whether or not someone took their pictures?

The list of questions goes on and on.

The goal of Partners In Health’s photographic exhibit was to inspire, not offend; to tell the truth about intolerable conditions rather than whitewash them; to bring faculty and students and those who live or visit Harvard into a movement to understand what is happening in the world today and to turn them away from morally flimsy and analytically shallow relativism or “political correctness.”

Writing this essay far from, but for, Harvard, I hear a nagging voice in my head. Why cross swords with those who support you? Why pick a fight with liberal sentiment? But the answer is clear too: because this desire to whitewash or hide real suffering is a perversion of our tasks. To understand the genesis of suffering is to reveal how structural violence is related (in its intimate details) to questions of human rights.

The relationship of poverty to human rights is no mystery to those who live in poverty. Every year for the past decade our Haitian co-workers have sponsored a conference on health and human rights. This year I almost missed it because of my own medical leave. I had returned to Harvard to receive the world’s finest medical care; we do not yet have an orthopedic surgeon here. My first foray out of the hospital was to return to Haiti for the health-and-human-rights conference. Sitting in a church—the area’s biggest building—I was surrounded by a few thousand people, only half of them able to fit in the hall. The rest were outside. The huge crowd included patients—definitely not clients—many of them the only persons with AIDS in Haiti who were actually receiving proper therapy for the disease. Those patients were from central Haiti, where we have been providing AIDS care at no cost to the patient because we believe that health care is a human right. Many more in the audience were dying of untreated or inappropriately treated AIDS. Those individuals—not yet patients, to their dismay—were from the capital city and were there to fight for their right to health care.

I sat in that church and thought about my own good fortune, which I confess had not been my mood upon leaving the Harvard hospital in which I received my care. My thoughts had been: Why did this happen to me? What if I were left unable to walk the hills of Haiti ever again? Would I walk with a limp? Would the pain ever abate fully? But these concerns faded as I sat and heard the comments of people living with both HIV and poverty. And when it was my turn to speak, I abandoned my planned discourse and instead spoke about a fractured leg. Not my own, but that of a young Haitian man, a Partners In Health employee who’d taken a bullet in the leg a few years previously. I had only months ago ended yet another angry book with the question, “Should people have the right to orthopedic hardware?”

Such a question would strike many of my colleagues in the human rights community as absurd. But I meant it then, before I had a titanium plate placed against my own femur, and I mean it now. Should poor women have the right to benefit from early detection of breast cancer? And when it is detected, should they have the right to therapy? Should people dying of AIDS be spared only if they can pay for the antiretroviral therapies that will save them?

What exactly is this all about? For, clearly, David Walton is correct: structural violence and one of its sharpest blades (lack of access to care for poor women) were at the heart of his photograph. So the photograph itself could not be termed “not at all appropriate” to the display. Was it about the politics of representation? Again, this is an often debased debate, since external determinants of disease—poverty, inequalities of all sorts—are considered “off topic” by many seminar-room warriors. We need to ensure that our classrooms and public spaces make room for a discussion of human rights that includes the right to health care, schooling, food, and lodging.

The people living with HIV who spoke in the conference were aware of the long list of reasons marshaled by university-trained experts to show us why we cannot provide “cost-effective” care for AIDS or breast cancer in the world’s poorest communities. The list of reasons is not often overtly racist or sexist and does not include anything approaching frank contempt. The reasons (or excuses) for not addressing these complex diseases are framed more subtly. We’ve heard, for example, the Africans have a “different concept of time” and so cannot adhere to complex therapeutic regimens. Even a “lack of watches” has been advanced as a reason not to treat. The Haitian AIDS sufferers knew these stories and retorted, as they had done in a previous conference on health and human rights, “We may be poor, but we’re not stupid.” They were familiar with the thousand other excuses we dish up to explain the persistence of poverty, the growth of inequality, and the futility of trying to fight diseases as complex as breast cancer and AIDS in places as poor as Haiti.

Relativism is a part of the problem. Why is it impolitic in our grove to argue that dying of never-treated AIDS in a dirt-floored hut is worse than dying of AIDS in a comfortable hospice in Boston, after having failed a decade of therapy? I’ve been present for both kinds of death—at matside and at bedside. And no death of a young person can reasonably be called good. But I’ve seen almost nothing worse than dying of AIDS and poverty, incontinent and dirty and hungry and thirsty and in pain. That’s the fate that structural violence reserves for those living with both poverty and disease.

Whether or not we see these horrible deaths, whether or not we take down the photograph, they are happening every day. We can continue to demand enhanced rights for those who have, already, many rights. But we cannot and should not allow relativism or fear to creep into our analysis or our activism. It may not come as a shock to you to learn that some of those living in great poverty believe you and I have too many rights (as one Haitian said to me, with what I thought was a bitter humor: “I suppose I’ll never fly in a plane”). Those who must face structural violence every day encounter precious little in the way of support for the right to food, water, housing, or medical care. There is no international struggle for the right to chemotherapy or even a mastectomy.

Shouldn’t there be?

For such a movement to come about, we need to rehabilitate a series of sentiments long out of fashion in academic circles: compassion; indignation on behalf not of oneself but of the less fortunate; empathy; and even pity. And is it merely ridiculous to suggest, as Auden did decades ago, that we must learn to love one another or die?

Fall 2003, Volume III, Number 1

Paul Farmer, a physician-anthropologist, has lived and worked between Harvard and Haiti for 20 years. Presley Professor of Medical Anthropology at Harvard Medical School, he divides his clinical time between the Clinique Bon Sauveur in Cange, Haiti, and Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where he serves as Chief of the Division of Social Medicine and Health Inequalities. His most recent book is Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor (University of California Press).

David Walton is in his first year of a residency in internal medicine at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and divides his time between Boston and a public clinic in Central Haiti. Walton has worked in both of rural Haiti’s first AIDS clinics and has already launched a career in infectious disease. Farmer and Walton thank Leslie Fleming and Haun Saussy for their help with this essay.

Related Articles

Human Rights: Editor’s Letter

During the day, I edit story after story on human rights for the Fall issue of ReVista. During the evening, I work on my biography of Irma Flaquer, a courageous Guatemalan journalist who was…

ONGs en América Latina y los derechos humanos

Las ONG ofrecen mil modos de recordar la dignidad humana a los gobiernos y las sociedades. Las dos experiencias que esbozo en esta nota reflejan algunas de las estrategias asumidas por…

Peru’s Human Rights Coordinating Committee

The human rights abuses that devastated Peru from the early 1980s to the mid 1990s are once again an issue of debate in that country with the release of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation’s…