A Review of Sustaining Life: How Human Health Depends on Biodiversity

Rx for Human (and Planetary) Health

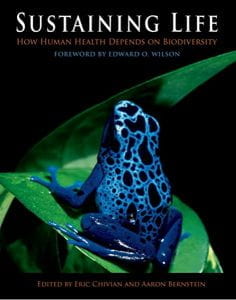

Sustaining Life: How Human Health Depends on Biodiversity Edited by Eric Chivian and Aaron Bernstein Oxford University Press, 2008, 542 pp.

“The entire world is a battlefield, and we must decide whether we are to be the soldiers that kill upon that field, or the leaders who sign a firm and lasting peace with the planet.”

—President of the Republic of Costa Rica

“We will not give up on life on Earth”

Launch of Peace with Nature Initiative

National Theater, San José

July 6, 2007

In September 2004, Hurricanes Jeanne and Ivan struck the Caribbean and southern United States in rapid succession. Damage to Haiti in the West Indies was particularly severe. High winds and intense rains caused widespread flooding and mudslides, which devastated urban population centers and rural villages alike. Jeanne alone killed at least 2,000 people and left an estimated additional 300,000 homeless. Scenes of stunned citizens walking chest deep in water that had inundated their homes were broadcast around the globe.

Less than a month later, the Global Amphibian Assessment (GAA), a multi-year effort mounted by The World Conservation Union (IUCN) to evaluate the abundance and geographic range, population trends and risk of extinction of the world’s approximately 6,000 species of amphibians, released its findings in a widely publicized article in Science magazine.

Among the GAA’s shocking findings was that nearly half (48%) of the amphibian species native to the West Indies—all of them frogs—were threatened with extinction if they were not already extinct. The situation was most severe for Haiti, where nearly all (92%) of the native species known at that time were regarded as vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered. Indeed, most of these species are expected to become extinct in the next 20 years in the absence of intense and costly actions to save them.

Unrelated events? Hardly, for the same primary cause that has left Haitian cities and villages susceptible to severe flooding and devastation during hurricanes and other tropical storms—deforestation of natural woodlands, especially in steep, mountainous areas—underlies the decline and eventual disappearance of much of the country’s native biodiversity. Indeed, the primary reason invoked for the precipitous population decline of all 47 species of native Haitian amphibians threatened with extinction is human-mediated loss of their forest habitats. Meanwhile, a UN-sponsored assessment of the damage wrought by Jeanne and Ivan concludes:

Haiti relies upon steep hillsides to meet much of its agricultural production. Erosion is a serious problem affecting the agricultural sector, with an annual soil loss of about 36 million tons. This has led to declining crop yields, damage to downstream lands and the destruction of coastal marine resources. Most hillsides are highly eroded and widely practiced cropping systems encourage continued erosion. Pre-existing factors such as deforestation…may combine with storm effects to increase future risks and vulnerability….

—“Hurricanes Ivan and Jeanne in Haiti, Grenada and the Dominican Republic: A rapid environmental impact assessment,” compiled by the Joint UNEP/OCHA Environment Unit based on assessment reports from UN Disaster Assessment and Coordination (UNDAC) team members, October 2004.

This example encapsulates the general and fundamental relationship between the Earth’s biological diversity and human health and wellbeing that is explored in impressive fashion in the new book edited by Eric Chivian and Aaron Bernstein,Sustaining Life: How Human Health Depends on Biodiversity.

Chivian directs Harvard Medical School’s Center for Health and the Global Environment, which for many years has sought to promote greater awareness of the reciprocal and causal links between global biodiversity loss and threats to human health. Bernstein, also affiliated with the Center, is a resident pediatrician at Harvard Medical School and Boston University School of Medicine. Their contributions to the present volume, however, go well beyond simply editing; the two of them jointly authored or co-authored (with additional specialists) seven of the book’s ten chapters.

The major topics covered can be broken down roughly as follows: what is biodiversity, how is it threatened by human activity, and what can individuals do to help conserve it (3 chapters); ecosystem services (1 chapter); the relation of biodiversity to medicine, human infectious diseases, and biomedical research (3 chapters); and biodiversity and food production (2 chapters). All of these topics are au courant, and many, such as the promise and pitfalls of genetically modified (GM) foods, are controversial. Specialist (outside) chapter authors are well chosen. They, combined with 25 additional “contributing authors” (who wrote particular sections of individual chapters) and more than 60 chapter reviewers, all of whom are listed in front of the index, provide the book with the necessary backbone required for it to be considered an authoritative source on the topics covered. Additional intellectual and societal heft is conferred by the brief foreword and prologue by Harvard biologist Edward O. Wilson and former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, respectively. The publication quality is high, and I encountered very few factual or stylistic errors (one of them being, in the caption to Figure 1.3, an amusing but fanciful definition of DNA barcoding, a recently developed technique for identifying biological species from DNA sequence data). The presentation also contains many attractive and informative illustrations, including a large number in color.

This is a scholarly work, but one that assumes very little specialized background knowledge on the part of the reader. It’s intended for the general reader and policy-makers, especially those who might find themselves in a position to remediate environmental problems. It also could effectively serve as a textbook for college-level courses that seek to address the consequences of global environmental change for biological diversity and human society. As a whole, the contents offer a comprehensive and novel approach to addressing the link between biodiversity and human health. I really can’t think of another treatment with this focus of equivalent breadth and depth. It’s also an interesting read.

Virtually all of the book’s topics and main themes are relevant to contemporary Latin America, and their consideration is very timely. For many kinds of organisms, the New World tropics hold more species than any other comparably sized region of the world, and most of these species are found nowhere else. Hence, the fate of Latin American biodiversity is of global significance. Moreover, had the authors wanted to, they easily could have provided examples of each topic solely from Central and South America and their adjacent seas. Medicines derived from naturally occurring compounds? How about the antimalarial drug quinine, derived from the bark of cinchona trees native to the Amazon basin. (“Peruvian bark” to 19th Century Europeans desperate for a cure, it is still popular among contemporary herbalists and homeopaths.) Or epibatidine, a highly potent compound isolated from the skin of the Ecuadorian Poison Frog, Epipedobates tricolor, which is contributing to the development of a whole new class of analgesics, or pain-killers. Destruction and fragmentation of natural habitats promoting the spread of human infectious disease? A catastrophic consequence of the large-scale conversion of much of the Argentine pampas into cornfields in the 1950s was recurrent outbreaks of Argentine hemorrhagic fever (AHF), a frequently fatal illness, in adjacent human settlements. Ultimately, these outbreaks were traced to population explosions of one particular species of native mouse, the natural “reservoir” of the AHT virus, in response to altered land use.

But what about the future? As nicely explained in the closing chapter by McNeely and colleagues (“What individuals can do to help conserve biodiversity”), a helpful way to evaluate the environmental impact or cost of any human population is through estimates of its “ecological footprint”—the amount of biologically productive land it needs to obtain all the resources it consumes and to process its wastes. Not surprisingly, recent estimates are highest for North America and Western Europe and lowest for Africa and the Asia-Pacific region. Values for Latin America and the Caribbean are less than half that of North America, but still higher than can be sustained on a permanent basis given current population sizes. Moreover, as these countries’ economies expand, standards of living increase, and human populations grow, their footprints, too, will enlarge, further compounding present problems and future threats.

Thus, Latin America today finds itself at an important ecological crossroads. Extending current trends of consumption and waste ultimately will extract a tremendous cost in terms of environmental destruction and diminished quality of human life. You cannot fool Mother Nature. There are, however, more promising alternatives, which also present opportunities for Latin America to lead the way for both more industrialized and other developing regions. One was offered in 2007 by Costa Rica’s president, Óscar Arias Sánchez, in announcing his country’s “Peace with Nature” initiative (Paz Con La Naturaleza), quoted at the beginning of this article. This bold plan, already being implemented, would make Costa Rica’s economy “carbon neutral” by 2021; design and implement a national environmental action plan; significantly expand areas of natural forest cover and the size of protected areas; and install an ambitious curriculum of sustainable development and environmental education in elementary and high schools. Poverty alleviation and economic development are not incompatible with protection of the environment and conservation of biodiversity. Ultimately, appeals on behalf of human health and wellbeing may be the most successful means of accomplishing all these ends.

Spring 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

James Hanken is the Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology, curator in herpetology, and director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, and a professor of biology in Harvard’s Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology. He chairs the steering committee of the Encyclopedia of Life, an internet site that provides information about the biology of all living species.

Related Articles

Heaven Above

Lasers, silicon-based light detectors, supercomputers, and giant glass disks all contribute to new techniques for astronomers to discover the properties of our universe. But one of the most…

Parallel Worlds of Mexican Cosmology

You could call it a treasure map, a time machine or a 16th century painted labyrinth. For me it became a magical board game filled with pictures of characters whose personalities and…

Astronomers in Mexico

Why astronomy? And why in Mexico? Science is an international effort. Newton’s law of gravitation does not have nationality, says the philosopher. In actuality, however, nationality does…