The Birth of INCAE (1963-1965)

A view from Harvard

Since the birth of INCAE was closely tied to the beginning of my career at Harvard Business School, the reader will perhaps forgive the autobiographical tone of these reflections. And right at the start, it should be said that both beginnings were marked by uncertainty; there were reasons to doubt that either would succeed. I like to think the infants nourished each other.

In February 1963, after an unsuccessful run for the U.S. Senate, I joined the faculty of Harvard Business School on a very temporary basis to help direct the division of international activities, which oversaw various management schools Harvard had set up in the Philippines, India, Turkey, and later Iran. As assistant secretary of labor for international affairs during John F. Kennedy’s administration, I had many friends in Washington, including Walt Rostow, then head of the State Department’s policy planning staff. When I told Walt about the School’s desire to be useful in Latin America, he immediately suggested that Central America might be the appropriate place for us to go. The need for managers was great, he said, and funding for Harvard’s effort could undoubtedly be arranged through the Agency for International Development (AID) as part of Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress.

The Central American site seemed promising to me because of the research and learning opportunities it offered HBS six very different countries, in varying stages of development, engaged in creating new regional organizations to manage their increasing interdependence. Since I suspected there might be hesitancy about government funding, I asked Walt if the invitation for the project might come directly from the President. I soon found myself hacking out a draft for President Kennedy on Walt’s typewriter. It said, in part, “My recent talks with the Presidents of the Central American nations reemphasized our mutual concern for the rapid development of human resources in this critical area. The participation of the Business School in a program to strengthen management would constitute a vital step toward sound regional integration, a major objective of the Alliance for Progress.”

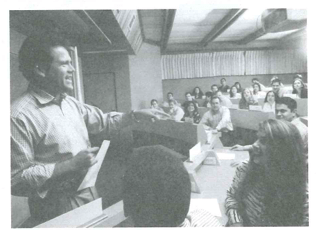

Two HBS senior professors, Henry Arthur and Thomas C. Raymond, traveled with me to Central America to meet with business and university leaders. We met with mixed reactions about establishing a graduate school of management in the region. Many felt that management could only be learned by experience and doubted that professors from the United States, ignorant of Central America, would be of much help. University officials viewed the case method and field-based research with suspicion, preferring theoretical conceptions of higher education.

Then one evening at an embassy reception in San Salvador, I met Francisco de Sola. He took me aside in the serious way he had and asked me to tell him what we at Harvard had in mind. I described the case method: going out into the fields and factories of Central America, identifying the actual problems that managers confronted, analyzing how they were dealing with them, and discussing possible improvements. We certainly were not suggesting that we as teachers, especially Harvard teachers, had the answer to Central America’s problems. Those would have to come from the region itself. After three hours of conversation, Don Chico said, “We have no choice. We must do it.” That, I think, was the moment INCAE was conceived.

Managing the introduction of change seemed to me of paramount importance to Central America and thus to INCAE; Francisco de Sola and the other members of what became INCAE’s board of directors agreed. This commitment to the management of change as well as the case method itself has meant that INCAE has never been the captive of any ideology capitalism, socialism, or whatever. It also established early that INCAE’s primary concern was to train managers for both the private and public sector in order to promote the welfare of the communities it served.

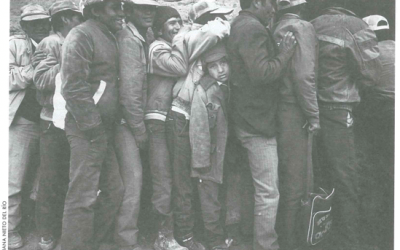

There was much excitement in the early days and many problems. We began by organizing a series of four-week seminars for business leaders and government officials. The second seminar we held was in Boquete, a beautiful, remote village in the mountains of western Panama. We chose the site not wanting executives to be distracted by urban diversions. The seminar was held in a local high school which had one large open air room built of concrete with a very high ceiling. The first problem was acoustics: voices were swallowed up by echoes. A rug was flown up in a DC3 from Panama City. Then there was the blackboard problem. One of the most challenging aspects of the Boquete program was the erection of blackboards, which Harvard professors use prodigiously. Two-by-fours had to be nailed together to reach from the floor to the ceiling, which was about 40 feet in the air, then braced, framed and made to hold the massive boards. My Spanish was none too good, and my carpentry worse; nevertheless, even though local carpenters found the requirements appalling, we finally erected a structure that withstood the pounding my colleagues gave it. The simultaneous interpreters from New York in those days arrived to discover that none of their equipment worked. Happily, a highly skilled electrician with the local phone company passed by at the crucial time, and all was saved.

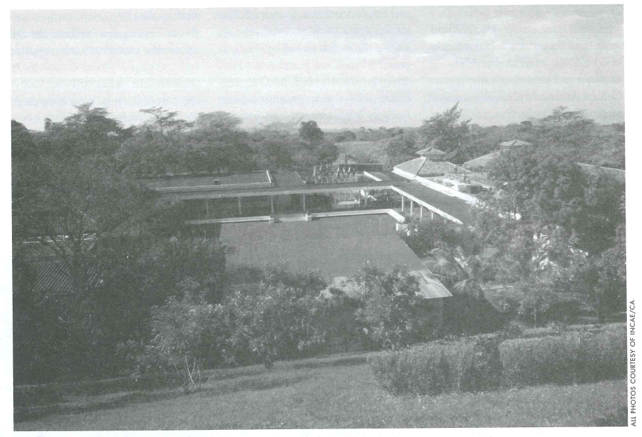

Boquete proved productive. As the seminar drew to a close, the participants drafted a statement on “future social and economic changes in Central America and Panama.” In the fall of 1964, INCAE directors decided that the institution should be located in Nicaragua because of the Nicaraguan business community’s pledge of free land and $250,000, as well as the fact that Nicaragua had fewer regional agencies than the other countries. A team from Harvard’s Graduate School of design arrived, was flown over central Nicaragua, spent days driving here and there, and eventually recommended the site on which one of INCAE’s campuses is located today, a few miles outside of Managua in the highlands.

The main campus is now in Costa Rica, and the world has changed in the last 30 years. It has become more interdependent and more competitive. There is no possibility of isolation; there is no place to hide.

To produce the changes Central America needs, to raise the living standards, and to retain control of its political and economic systems, Central America must be competitive. This requires a community committed to high levels of education for all of its people. It requires a community of managers who see their purpose as the service of community needs and their relations with those whom they manage as being cooperative rather than adversarial. These are the prerequisites for communitarian success in the world today, Their achievement is the challenge facing INCAE and its graduates.

Fall 1999

George Cabot Lodge is Jaime and Josefina Chua Tiampo Professor of Business Administration (Emeritus). He was assistant secretary of labor for international affairs in both the Eisenhower and Kennedy years (from 1957 to 1961) and one of the founders of INCAE.

Related Articles

Poverty or Potential?

Teresa stops me three blocks from Nueva Imperial’s main plaza on a quiet Wednesday morning, eager to chat. She is wearing a light blue sweater and a matching blue headband glowing slightly against her dark black hair.

Infections and Inequalities

I read Paul Farmer’s book while on a short visit to Venezuela, and found that setting, at this historical moment in time, particularly pertinent and highly conducive to the arguments Farmer…

Proclaiming the Jubilee

Carmen Rodríguez heads the Charismatic Movement in a sprawling shantytown parish south of Lima, Peru. She and other lay leaders of the Lurín Diocese have been preparing for the…