The Community Perspective

Learning to Listen in Northeast Brazil

The driver was yelling out in Portuguese with the rough-hewn rural accents of Northeastern Brazil: “This is the woman who is looking for the dead children. I have told her she should come in and see some of the children who are still alive, but she is interested only in the dead children.”

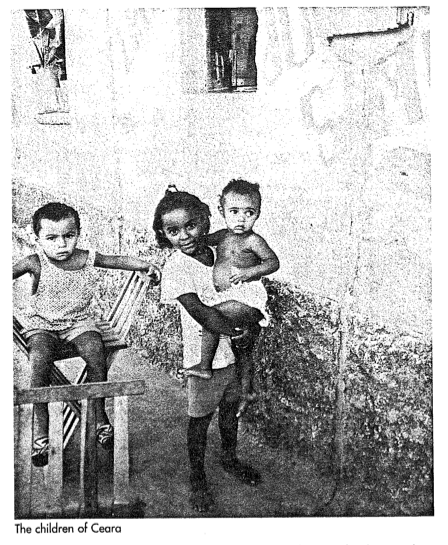

Ana Cristina Terra de Souza, a doctoral student at Harvard’s School of Public Health, was indeed only looking for the “dead children,” actually, the mothers of children who had died in the previous 12 months. She was seeking to do a “verbal autopsy” of the children in the communities of Ceará, far from the urban middle-class environment in which she had grown up far to the south in urban Rio de Janeiro.

During her summer project, funded in part with a DRCLAS travel grant, she learned more of the perspective of the mothers from the 40 women community health workers who became her guides, her colleagues, her mirror into the community.

The community health workers had collected information on vital status and health indicators, which Terra de Souza, who was trained as a dentist in Rio before going to study at HSPH, was able to use as a basis for her field research.

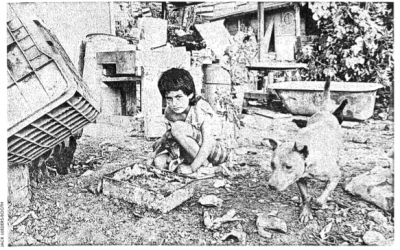

Ceara is one of the poorest states in Northeast Brazil. According to a recent census, 34.6 percent of the population lives in rural areas, 83 percent of families living in the rural areas earn less than $200 monthly, half of all women of reproductive age are illiterate, 45 percent of the houses are made of mud and sticks, more than half the population does not have access to potable water, and 70 percent of households do not have any type of sanitary facilities. Out of every thousand infants born, 65 die. According to 1995 data from the community health workers’ program, diarrhea and acute respiratory infections were 9.6 and 6.9 per thousand live births, respectively.

The statistics gathered by the community health workers, most of whom were selected by their communities and all of whom lived there, revealed the extent of the problem. But it was not until she began to go house to house with the workers that it became a reality.

“You read all these articles; you research all these reports, but you find there’s a real daily struggle that perhaps you never even imagined. It becomes part of you,” she said. “The community health workers came and talked and worked with these people everyday, and they made the numbers become meaningful to me. I could put the stories with the numbers.”

The lessons learned from the field research were many. According to Terra de Souza, her field research reaffirmed the importance of the social context of evaluation research including the potential uses of research findings for decision-making and improvement of programs and services to better the lives of children, families, and communities. “I believe that it is only when communities and programs are truly engaged in the inquiry that we as researchers can make substantial contributions to the improvements of social programs designed to better the lives of individuals and communities,” she empahsized.

She also found that the combination of quantitative and qualitative methods– research that brings together different disciplines and applies multiple methodologies in order to properly understand and evaluate public health and social programs– is more likely to be effective in understanding and evaluating public health and social programs than those with a single focus. The quantitative data supported the stories and the stories (mothers’) illustrated in a meaningful way the results summarized by the statistics.

The paid community health workers, “Programa de Agentes Comunitarios” – P.A.C.S–all of them women, were part of a state government program started in 1987, and now operating in 182 of the 183 municipalities in Ceara, covering both rural and urban areas. They were all trained by nurses, and some of them had become leaders in their communities.

“It helps the women they work with, but it’s also very empowering to the women themselves. They gain a vast store of empirical knowledge. They may have always been born leaders and helped and given advice, but the program meant that they were being officially acknowledged by the system.”

Community health workers visit each of their assigned 50 to 250 families to provide health and nutrition education, weigh children under two years of age and collect information on vital status and health indicators once a month. CHWs report monthly to a supervisor (nurse) who aggregates the data at the municipality level.

Terra de Souza used the P.A.C.S. data for part of her research in evaluating variations in infant mortality and undernutrition among municipalities in the State of Ceara. However, in the process of designing the research (she had worked two summers before the actual field research for the verbal autopsy project with the P.A.C.S.. One of these summers was also funded (entirely) by the DRCLAS),both Terra de Souza and the P.A.C.S. program officials realized that while statistics were helpful in assessing the community-impact of the different program interventions, they provided no information on the actual circumstances of infant deaths. Therefore, the second component of the outcome evaluation involved the design and implementation of a verbal autopsy study, integrating quantitative and qualitative techniques to investigate in-depth the circumstances of infant deaths, more specifically mothers’ health care seeking behaviors during their infants fatal illnesses.

The interviews took place in 11 different municipalities, and involved both close-and open-ended questions on the causes and circumstances of death, use of indigenous remedies, and on contacts with health care providers during the terminal illness. The mothers interviewed were asked about the illness that led to the infant’s death and the events and barriers associated with seeking health care. Most mothers described symptoms such as unexplained crying, high temperature, vomiting, loose stools, and serious breathing difficulties as reasons for seeking treatment. According to Terra de Souza, three themes emerged from the open-ended interviews: delay in seeking medical care, delay in receiving medical care, and ineffective medical care.

Over and over again, mothers told of frustrated attempts to get appropriate care. “…He had diarrhea for several days. I sought treatment at the health center. The doctor examined him, prescribed some medicine, and told me that he needed intensive care not available. He was referred to a hospital in the neighboring municipality…but, when I got to the hospital, I was told it was too late, that there wasn’t anything they could do at the hospital to keep him from dying…,”one mother told Terra de Souza and a community health worker.

The infant died at home two days later.

Ana Cristina Terra de Souza interviews a family who has lost a child.

Despite the sadness of the stories, they also led to clues for improvement. Given that most infant deaths are due to diarrhea and respiratory infections, and that delays in seeking treatment for these conditions are common, health education and communication efforts for child survival can help underscore the severe nature of these diseases in young infants, with emphasis on the need to start oral rehydration therapy as soon as possible.

Another thing that she learned from her interaction with the mothers and the community health workers was that “long-term strategies that address the social and ecconomic conditions in which these deaths happen are necessary.”

“This research reaffirmed for me that the importance of doing research is zero if there is no community involvement,” she said. “The community health workers had a better understanding of all these multiple factors. They learned from my questions, but I also learned from theirs. I came to ask about the medical system, but they’re telling me about their traditional healers. I became so aware of my perspective as a middle-class woman. It was this interaction and this dialogue that was empowering for all of us. We groped at the complexity from both sides. Even though I’m Brazilian, I thought, well, it’s a simple matter. It’s because they’re poor and don’t know the scientific basis of things. But what I learned is that with all their constraints, they do their best.”

“Right now, I am preparing to go back to Ceara to report on the findings of the research at both state and local-levels,” concludes Terra de Souza. ” I have been working on ways to develop community forum methods to involve groups of people from different sector of communities to set issue agendas and identify acceptable actions. I believe that even though crucial, this “last” phase of the research, dissemination of results is often overlooked.”

Spring 1998

Related Articles

The Social Agenda in Latin America

If the 1980s were the era of economic policy reform in Latin America, the 1990s have become the era of social sector reform. Indeed, a consensus is now forming that delivery of health care…

A Mellon Update

More than 23 Latin American archives and libraries from Mexico to Rio de Janeiro have received grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to upgrade or preserve their facilities. The…

From Havana to HUD

Kennedy School Assistant Professor Xavier de Souza Briggs, who took a group of 17 graduate public policy students on a one-week study tour of Cuba last year, has now embarked on…