The Distortion of History

A Form of Genocide

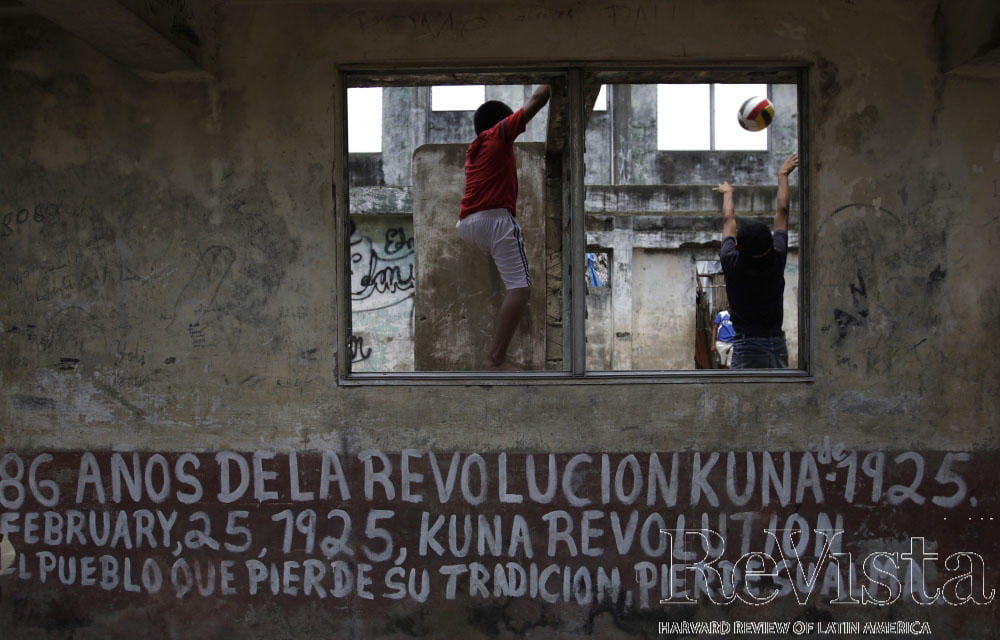

The sign reads, “86 Years of the 1925 Kuna Revolution; a people that loses its tradition loses its soul.” Photo courtesy of La Prensa/Bienvenido Velasco.

Panamá was already inhabited 11,000 years ago. Its history, nonetheless, is written from two perspectives: that of archaeologists and of historians. The British archaeologist Richard Cooke found classic stone tools used as spearheads and butcher knives from that early era in Laka Alajuela in Colón and Sarigua in Herrera. However, conventional historians begin the history of Panamá in 1501, when it was “discovered” by the Spaniard Rodrigo Galván de Bastidas.

Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano once asked sarcastically, “Are native peoples blind?” After all they lived by the Pacific Ocean, which allegedly had to be “discovered” by the Spanish. What in reality was discovered was the official Panamá only, the Panamá that is celebrated by the government with liquor and festivities, commemorating the date of September 25, 1513, when a Spanish adventurer first saw the Pacific Ocean (some say he arrived on September 26).

Actually, it was Bab Giakwa (known as Panquiaco in the Spanish dialect of Panamá), a man from the Dule (Guna) nation, who told Vasco Núñez de Balboa, on whose ship Galván sailed, about the Pacific Ocean, an ocean that our fellow Guna knew intimately from his childhood. Spanish priest Bartolomé de Las Casas writes that Bab Giakwa, dismayed because the Spaniards were displacing native peoples from their lands in their lust for gold, offered to guide them to the Pacific Ocean, “the southern sea.” Las Casas adds that Vasco Núñez had written to his admiral that he had hanged 30 native chiefs and was ready to hang anyone else who got in the way of the Spaniards’ goals; by doing so, he was demonstrating his service to God and the Spanish crown (Bartolomé de las Casas: Historia de las Indias. T.III. Caracas: Biblioteca Ayacucho, 1986. Pp.154-157).

Balboa himself admits that he portrayed his arrival to the Pacific Ocean in a January 20, 1513, letter to the King of Spain in a false and hypocritical way, saying that the native peoples had been treated very well and had told him about great quantities of gold.

In general, the Panamanian ladino historian interprets history from a very Hispanic point of view. There are indeed exceptions, such as Ana Elena Porras, Roberto de La Guardia, Jorge Kam, Francisco Herrera, Celestino Araúz y Bernal Castillo. But on the whole, as the poet and essayist Roque Javier Laurenza points out, Panamanian history is written by “clumsy novelists.”

As Isidro A. Beluche recommends:

Children, youth and adults of Panamá must acquaint themselves with the social institutions, cultural ways and the great deeds of the inhabitants of the isthmus before the arrival of the peninsular invaders, so that they will be able to understand the indigenous soul and to make sure that the written measures consecrated in our Constitution and the laws being developed or already promulgated in regards to indigenist policy (articles 94, 95 and 96 of the Constitution) be carried out in practice. (Isidro A. Beluche, “Interpretación de la historia nacional y americana,” in Memoria del Primer Congreso, April 18-22, 1956.)

This First [Indigenous] Congress, at which Beluche spoke, resolved in part “to ask the Education Ministry to name a commission to revise the programs and texts of Panamanian and [Latin] American history to adapt them to a genuinely American point of view, that interprets indigenous sentiment in the study of the process of the Spanish invasion and domination of America and especially in the isthmus of Panamá.” The Congress also resolved to “ask the government of Panamá to honor the forefathers of the indigenous race who tenaciously resisted the conquerors, so that these figures can stimulate our people to defend American and national sovereignty against any attempt at meddling in continental affairs [sic] through force or the intervention of foreign governments in our hemisphere.”

Twenty-five years later, in the Declaration of San José entitled “UNESCO and the Struggle Against Ethnocide,” in point 4, the international organization stressed: “Since the European invasion, the Indian peoples of America have seen their history denied or distorted, despite their great contributions to the progress of mankind, which has led to the negation of their very existence. We reject this unacceptable representation.”

Diana Candanedo (Solidarity Committee with the Guaymi people); Bernardo Jaén (from the Regional Coordinating Body of the Indian People of Central America) and Doris Rojas from the Universidad de Panamá all signed the declaration on behalf of Panamá.

Through the work of Las Casas, the three-volume Historia de las Indias, we can determine that our history as generally written by ladinos is a fraud and totally lacks appreciation both for the indigenous people and for the intelligence of humanity. The point of view of many of these Hispano-centric writers might even be considered unconstitutional, since article 81 of the Panamanian Constitution reads, “The national culture is composed of the artistic, philosophical and scientific manifestations produced by Panamanians throughout all time. The state will promote, develop and protect this cultural patrimony.”

As we have seen, the first Panamanian lived around 11,000 years ago. To say otherwise, to create a different type of false memory, is an act of cultural genocide. We are all Bab Giakwa, who as a boy saw the oceans, both the Atlantic and the Pacific, from the highest point of Demar Dake Yala, “the hill that overlooks both seas.” In any decent country, Bab Giakwa, the Panamanian who discovered the Pacific—the sea of the South—would be declared a hero of the motherland by the National Assembly.

Spring 2013, Volume XII, Number 3

Arysteides Turpana is a Panamanian professor, writer and poet of Guna origin.

Related Articles

The Panamanian Novel

Pueblos perdidos, the novel which earned Gil B. Tejeira Panamá’s Miró Literary Prize for 1963, tells the story of Gatún Lake, at the time the largest artificial…

Panamanian Culture

Panamanian culture has roots in at least three continents. It’s a heterogeneous culture, embracing elements from various communities that coexist peacefully…

Panama City

On May 8, 2003, the Bay of Panamá suddenly turned red. The Coca-Cola factory had spilled a massive amount of non-toxic red chemical dye and was eventually…