The Elderly and the Revolution

Sparking a Crisis in Nicaragua

After the Sandinista revolutionary government was voted out of power in 1990, Nicaragua mostly flew under the international radar. On the infrequent occasions that foreign media spotlighted the small Central American country, writers gushed about its potential as an up-and-coming tourist destination or the next big development success story.

The situation suddenly changed last year, when an unprecedented wave of popular protests rocked the country’s decade-old authoritarian government. President Daniel Ortega’s decision to respond with police and paramilitary violence, and his refusal to consider a democratic transition which would threaten his family’s grip on power, have mired the country in a prolonged crisis which, according to United Nation reports, has left at least 300 dead and more than 2,000 injured. Now, rather than seeing it as “the next Costa Rica,” Latin America watchers fear that Nicaragua will plunge further into chaos and threaten the rest of the region’s stability in the process. But what do the elderly have to do with it?

Ortega, a 72-year old former Marxist revolutionary with the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), returned to power through elections in 2006. For the following decade, most Nicaraguans—especially the country’s traditional capitalist class—apathetically condoned his family’s co-opting of state institutions, harassment of dissenters, and conspicuous efforts to create a cult of personality around the dynastic political project he shares with his wife, Rosario Murillo. Popular protests were surprisingly far and few between. Nonetheless, subsequent events proved that deep resentments were lurking just below the surface. It would only take a single spark to light the prairie fire.

It came, unexpectedly, in the form of pension cuts. On April 18, the government announced a reform to the National Social Security Institute (known by its Spanish acronym, INSS) which would reduce pension payments to retirees while increasing the amount that workers and employers must contribute to the social security fund. Unlike Ortega’s myriad violations of the country’s constitution and democratic norms, which Nicaraguans’ indifferently accepted so long as the country was stable and growing, these changes struck directly at their wallets.

The next day, Nicaraguans took to the streets in numbers unusual in the Ortega era, and protested cybernetically with the hashtag #SOSINSS to demand the reform’s abrogation. The government responded in typical fashion, attempting to smother the outbreak by sending shock troops to attack the protests and censoring media coverage of the events. This approach had worked in the past, but this time it only fanned the flames. The rest is now history: the claiming of pension rights morphed into wider political demands for a democratic transition as the Ortega regime began responding with lethal force, thrusting the country into an endless less loop of repression, protests, and further repression.

The politically costly decision to cut pensions was the result of three main factors, each of which tells us something different about the regime’s underpinnings. First, the social security fund was going bankrupt. Independent investigations suggested that the government had arbitrarily withdrawn money from the social security fund and invested it in failed state-owned businesses and development projects, including some run by Ortega’s children. During sunnier economic days, such misuse of public resources could have been papered over. But generous aid from oil-rich Venezuela—which may have totaled as much as half a billion U.S. dollars at its peak—ended in 2014 when global commodity prices dropped and the South American country fell into a severe crisis. The pension reform, along with cuts to social programs and other reductions in government spending, was also an indirect response to this external shock. Third and finally, the International Monetary Fund had advised in favor of the measure. The 21st century FSLN, having abandoned socialist economics in favor of free market policies much more to the liking of the country’s traditional elite, has closely followed the recommendations of multilateral lending institutions in implementing its growth and poverty-reduction strategies. Such organizations have tended to prioritize a balanced budget, for which they believed this austerity measure was indispensable, as a pre-condition for major loans.

Though a popular reaction was not entirely surprising, the depth of the anger and the identity of the street demonstrators raises questions. Indeed, as one of Ortega’s top advisors noted in a Univision interview given in the midst of the protests, it wasn’t senior or middle-aged citizens—those most obviously affected by changes to retirement schemes—that hit the streets. Far from it. The protests first broke out in Managua’s universities, organized by young people several decades away from retirement age. Why did students take up the cause of the elderly, and what does this phenomenon tell us about the role of aging in driving political change in Latin America?

In developing countries where the social safety is particularly weak, even small adjustments to state pension programs can reverberate across several generations. In fact, not so many Nicaraguans actually rely on these payments; at a peak in early 2018, only 900,000 workers (one out of every four) were employed in the formal sector and therefore were registered in the INSS. Still, this significant cut in spending—which is, in effect, a tax on both workers and businesses to keep a government fund solvent—would, as private sector analysts warned, depress job creation as firms found it costlier to hire workers. Formal sector retirees are more likely to have children and grandchildren who, as members of the middle class, fill up the university halls where the protests began. Young people have good reason to be angry; when the state absconds its responsibility to care for the elderly, it falls on their progeny to eventually support them.

The material impact of pension cuts does not fully explain, however, why this tax protest evolved into something greater. The shell-shocked government actually backtracked on the reform within days, but the protests only grew in size, frequency and belligerence. While the #SOSINSS hashtag proliferated for a time, protestors began demanding the resignation of the police commissioner and the president. Clearly, the pension cuts were symbolic of larger grievances accumulated over the previous decade. To a citizen fed up with corruption and lack of transparency, the government’s self-interested use of pension funds to invest in other projects— effectively mortgaging the elderly’s future—struck a nerve. Those who bemoaned the need to affiliate with the ruling party to access certain state programs such as university scholarships or agricultural credits asked if such submission was even worthwhile. Sectors of society which had quietly looked away as Ortega consolidated a Sultanistic ruling style, such as the private sector associations, were furious that, as with most matters of public policy, nobody—not the legislature, civil society nor the elderly themselves—had any input on this decision. President Daniel Ortega and his inner circle had made the decision without consultation.

Most importantly, the governmental response showed Nicaraguans the extent to which dissent and protest had been criminalized under Ortega. Protests against the social security cuts were not motivated by opposition political parties, many of whom were perceived to be tacit allies of the ruling FSLN. But as the death toll mounted, university students—many of whom first encountered police repression when protesting the state’s inability to stop a forest fire at the Indio Maíz biological reserve—realized that they now were simply defending basic civil liberties. Demands for Ortega’s removal from power were driven by indignation over the repression, not the original policy. Those demands, predictably, engendered an even more ferocious state response. By the end of the summer, the UN human rights office reported that government repression and persecution had created a “climate of widespread terror.”

In other words, the episode demonstrated that the underlying problem was the closing of democratic spaces. In most societies, governments implement similar—or often more severe— austerity measures without hurling their countries into a months-long chaos. The difference is that in those countries, protests and other forms of participation are a normal feature of public life, even in less-than-democratic political systems. The pension cuts episode shows how, when you circumscribe democratic spaces to an extreme, closing off any escape valves for societal resentment, any minor injustice can degenerate into a situation of great political instability.

Perceived affronts against older citizens, at least in Nicaragua, seem to have a special ability to do so. In 2013, a smaller protest movement called #OCUPAINSS—also brutally, though not lethally, repressed—broke out when the government announced restrictions in who was eligible to receive the minimum state pension.

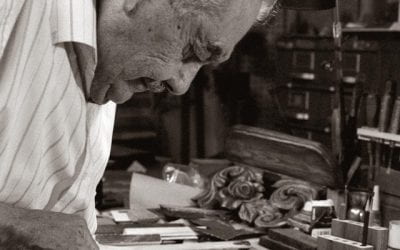

More than income, the relation between the elderly and political change might be summed up with one word: dignity. Like in many countries, grandparents and older workers embody familial leadership and responsibility, and therefore are viewed with special deference. They are also important vessels of historical memory, in the Nicaraguan case, one imbued with many past heroisms and hardships. Those who overthrew the Somoza dictatorship forty years ago are now retirement age. When ex-FSLN combatants and military veterans are detained or otherwise harassed by the regime, anti-Ortega citizens who identified with the Sandinista revolution are particularly incensed. As the recuperation and repurposing of revolutionary imagery and symbols against Ortega has demonstrated, young rebels are inspired by their living legends. Behind every teenager and 20-something in the barricades there was a strong anciano.

Winter 2019, Volume XVIII, Number 2

Mateo Cayetano Jarquín Chamorro is a Ph.D. candidate in Harvard’s Department of History. He is writing his thesis on the Sandinista Revolution.

Related Articles

Domestic Workers and Retirement

That day everyone was either crying or trying to hold back the tears. In the kitchen, Anita Tobon was crying too. Yet, Anita was crying very quietly as if her pain were insignificant or irrelevant…

The Living Dead vs. The Dying Living

One of the most quoted scenes from the movie Cockneys vs. Zombies (2012) by Matthias Hoene takes place in a London nursing home, where the survivors are a group of old men and women…

The Elderly as Historical Agents of Their Dignity and Destiny

I called my great-grandmother “Abuelita,” a Spanish term of endearment for “grandmother.” She lived to the very old age of ninety-three. I fondly remember from my early childhood the vision…