The Gift of Art

In memory of Stephanie, and in honor of Alejandro.

Stephanie Oduber and Alejandro Fajardo Escalona, 2021

My dear friend, Colombian pioneer performance artist, Maria Evelia Marmolejo, (Cali, Colombia, 1958) whom I met during the research for the exhibition Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985 at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles in 2017, caught Covid-19 in New York early in the pandemic when employees were not protected, and you could only justify your absence if you tested which was not widely available. She was fortunate that she did not end up in hospital, but it was hard. The deep cold in the bones you experience with Covid-19 brought back painful memories from her past during the armed conflict in Colombia. As the past and the present conflated, also the hard reality of the world, and the unnecessary deaths both during the pandemics, and because of social injustice and violence.

Still, deep during the pandemic, on November 18, 2020, we invited a small group of friends and artists to Mandragoras Art Space in Astoria, to view her performance Impunidad 2/Impunity 2.

Maria Evelia Marmolejo, Impunidad II, November 19, 2020 Photo: Maleni Guerrero Courtesy of Maria Evelia Marmolejo

Marmolejo’s experience of the coronavirus was political. Impunidad 2/Impunity 2, was an act of mourning and denunciation, as well as the embodiment of the loss and pain endured by friends, neighbors, the unknown, and her own experience of the disease. With this performance, she proposed to transfigure pain into a collective act of healing. The artist lay naked on the empty white space, and above her a row of candles was lit and as they melted, the hot wax fell along her body creating a delicate design of runny wax. It was a short, precise, and beautiful performance, that felt like a sacred ritual of mourning. In the artist’s words: “Many have died during this pandemic, but not all should have died. In an act of solidarity, my silent body will make a symbolic connection with the victims of Covid-19. Starting from the tradition of the funeral wake, as the last farewell to those who left alone due to contagion.” This performance was a powerful form of remembrance as an act of embodiment of the pain of self and others. Did this performance experienced by only few of us change anything? I do not think that this is the important question. My point is that art such as this is healing, even as an almost private and totally silent act. What is crucial is that it exists, that it took place, that it helped the artist heal her own trauma, in communion with others, and it was healing for us too.

Marmolejo and other artists whose work I had the opportunity of experiencing during the pandemic exemplifies the role of art in face of personal and collective situations of displacement, hardship, and social violence that have become aggravated with the Covid-19 pandemic. Artists in Latin America and the Latinx art communities have been raising awareness for decades about issues of state and social violence, gender violence, oppression, inequality, marginalization, and colonialism. Covid-19 brought to light and exacerbated what already existed and made it more palpable. The anxiety of temporary separation from family and friends, became a window to the traumatic experience of migration, exile, and enforced separation that millions experience in Latin America, in countries from Central America, the Caribbean and South America such as Venezuela. Losing a job or temporary financial hardship has also been a lens to the lives of millions of disenfranchised people whom before, during and after the pandemic live in terrible conditions which are now worse. We are all aware of the persistence of gender violence today, which worsened during the confinement. And over six million people have lost their lives worldwide because of Covid-19. When faced with this state of things, when tragedy strikes, can art provide answers or solace, go beyond the descriptive, have meaning, perhaps heal? I would like to argue, that yes. During this difficult period, I received several gifts of art, sometimes unexpectedly, others by reaching out to art history or my own memory of art, and in other cases, by looking at what some artists were doing, and the communities they were fostering.

One such artwork by Chilean artist Janet Toro (Chile 1963) provided a powerful embodied imaginary to grapple with the pain of separation, and the desolation of the pandemic. She shared two images of a private performance done on the window of her home.

Janet Toro, La flor negra. El encierro. Confinada en mi propia casa, durante la pandemia, Santiago, Chile 2020 Documentación fotográfica Marucela Ramírez Courtesy of Janet Toro

La Flor negra (The Black Flower), June 2020 in words of the artist describes how: “Confinement eats away, the control over each step tires. Social isolation is the regulation and management of the territories of the body, it is the abrupt forced separation, the domestic exile of feelings, in the great contemporary global prison.” In the photographs we observe the artist bending dangerously backward wearing a black cape over a white fabric covering the window, while her arms tilt in abandonment towards the void. In the second photograph her torso has been engulfed in the black cape, and we can only see the tips of her fingers. This is an image of mourning, of impossibility, representing the cancellation of the humanity of individuals. Why is this image powerful and touching? It is because Toro cared enough to create an image that embodied a sense of collective pain and desperation. In her gesture is represented our collective mourning, whereas, the temporary loss of freedom, or the loss of life, or the endurance of hardship.

For me art has never been solely about aesthetics, or progressive linearity, and it never made sense that certain histories like ours in Latin America or by Latinx artists were marginal, or that women were nowhere to be seen. Art is meaningful in a dialogical relation to life, not in the abstract sense, but in its connection to both the personal and the collective. Art has always been a powerful form of enquiry, a way to ask questions, to find answers, to imagine, to be touched, and to be inspired. Mostly, it has been argued that no matter how political or activist art is, its impact is only minor, and its ambitions mostly utopian. And we know that art has often been used for proselytizing reasons, not simply by art institutions and their agendas, but by governments and totalitarian regimes of power. Whereas you may want to debate what is art or not, for the argument of my essay, I do not distinguish here between for example a textile by an indigenous Mayan woman or a performance or a painting by self-defined artists. What matters is that these artistic expressions exist, constituting the proof of what the Anishinaabe Chippewa writer Gerald Vizenor coined as survivance, moving away from the traditional notions of pure survival and victimization promoted by colonial situations, to describe human persistence, resilience, being, and resistance, as a flourishing. They are meaningful to communities, families, neighbors, or individuals. I consider them all as possessing the impulse of life, creation, beauty, and meaning, and to have an important role in our lives, whereas for ritual, intellectual, aesthetic, or philosophical purposes, that are central to our existence. It does not matter that the Arpilleras during the Pinochet regime (1973-1990) embroidered their stories and protests for their communities without transcending to the status of museum icons, or that women weavers in indigenous communities such as the Mayan in Guatemala preserve still today a whole communitarian structure and culture with their beautiful textile traditions, while we do not know about it, or perhaps we wouldn’t consider appreciating. What matters is that they exist and are profoundly consequential.

As a Venezuelan, I carry the personal experience of having lost my home, a country and a life already years ago (I have written in this topic in: “Inner /Outer Exile in Contemporary Venezuelan Art” in dossier País Portátil: Contemporary Venezuelan Writing and Arts. Review 103: Literature and Arts of the Americas. Routledge in association with The City College of New York, CUNY. 2022). The pandemic, which separated me from my children, made me more aware than ever of how atomized the family is and how difficult it is to help each other in moments of hardship, and how deep is the desire to feel physical closeness, and to experience the certainty that comes with not being a migrant, in surroundings that are not loaded with constraints. Over the Fourth of July weekend in 2020, under the leadership of artists rafa esparza and Cassils, took place In Plain Sight, a coalition of 80 intersectional multidisciplinary artists, in partnership with over 30 organizations, united “to create an artwork dedicated to the abolition of immigrant detention and the United States culture of incarceration.” In Plain Site orchestrated all over the country sky-typing fleets writing artist-generated messages in water vapor over detention facilities, immigration courts and sites of historic relevance such as the Statue of Liberty. It was a powerful and touching event, in solidarity with immigrants in the context of an ongoing crisis of family separation and the terrible conditions of immigration centers, grown worse during the Covid-19 crisis. The event both poetic and political gave us the possibility of becoming aware and stand in solidarity with thousands of people on the chronic issue of immigration in the US. Still today, on the event website you can identify detention centers near you and help activists’ organization that are fighting on the ground to help immigrants. Using the sky and the internet to unite people for a common cause during the isolation of Covid-19, pointed to the creative, freeing ways artists can create community, bypassing the limits of institutionality, to reach thousands of people.

Installation View, Guadalupe Maravilla, Seven Ancestral Stomachs, P P O W, New York, February 26 – March 27, 2021. Courtesy of Guadalupe Maravilla and P·P·O·W, New York

While I was stationed in New York during the pandemic, I visited Guadalupe Maravilla’s Seven Ancestral Stomachs at P·P·O·W. I had seen some of his works online, but I was not prepared for the transformative experience that it is to view his art in the flesh. The monumental free-standing sculptures are musical instruments, “healing machines,” altars, headdresses, and installations. They are hybrid objects that embody the potentiality of healing. Their inception goes back to Maravilla’s own journey as an unaccompanied undocumented child flying the Salvadoran Civil War, his battle with cancer and his process of healing. Maravilla’s own history embodies the trauma of migration of thousands of people, and his art is created as an offering for sharing and curing through sound. Maravilla hosted a number of in-person sound baths, therapeutic healing rituals for small groups of people during the show’s running. I was fortunate to assist at a sound bath on a Thursday evening, on March 18, 2021. As I lay on the floor on a mat with my eyes closed, Guadalupe Maravilla and his wife Sam Xu activated the gongs in the sculptures and invited us to listen and experience in an atmosphere of safety and calm, indicating that these sounds would touch deep seated emotions, and to hydrate well following the experience. I did not know what to expect other than I trusted the artist because of the work. I was moved in ways beyond anything I could have imagined. I had received an unexpected gift, someone had offered us care, beauty and the experience of one of the most ancient forms of healing, which is sound, in exchange for our presence. How can we explain that Maravilla’s performative healing could nurture something so vital and profound, seamlessly moving between worlds, his personal experience, and the collective, between the gallery goer and the migrant, between the past and the present? The sound bath had provided a form of catalysis for my own journey too.

Stephanie Oduber, 2021

The hardest thing to happen to our family during the pandemic was the tragedy of losing my sister-in-law Stephanie Oduber in Maracaibo, Venezuela on July 31, 2021. Her life was cut short when my youngest brother Alejandro and Stephanie went cycling at dawn to join other cyclists and were attacked to steal their bicycles. Stephanie was killed at the age of 25 in cold blood when she had already surrendered, and my brother was shot but survived. Two men, 21 and 17 years old, left the two bleeding bodies on the street, taking her bicycle and their phones. The devastating loss and pain that ensued cannot be described especially for my brother Alejandro who had survived. Stephanie was special, a talented musician, loved and loving and soon to be traveling to Paris to continue her music studies. I do not think I will ever understand this level of violence of pervasive and senseless killing. After Stephanie’s death, there have been other cyclists that have died in similar ways in a country where impunity is the law.

This type of mindless violence has touched the lives of thousands upon thousands of people in Latin America, going back to colonial times, to dictatorships and civil wars, to conflict border zones, to drug cartel wars, to activists defending land rights today, to gender violence towards women and gender non-conforming individuals. There is no answer to tragedies like this, but I’m again reminded of brave artists who at times even risked their lives to produce denunciatory art, or who simply cared enough to pay attention and speak up.

Luz Donoso (con Hernan Parada y Patricia Saavedra) Acción de apoyo: intervención fotográfica en la vía pública Santiago de Chile, 1982 Cortesía archivo de Luz Donoso

I think of radical women such as Gloria Camiruaga (Chile, 1941-2006) who made intimate movies about torture to women during the Pinochet regime; Luz Donoso (Chile,1921-2008) who collected photographs of the disappeared and pasted them on street walls in the hope of helping finding them; Sonia Gutierrez’s (Colombia, 1947) paintings and prints of young bodies suspended in the air or tied to beds subjected to torture during the Colombian armed conflict.

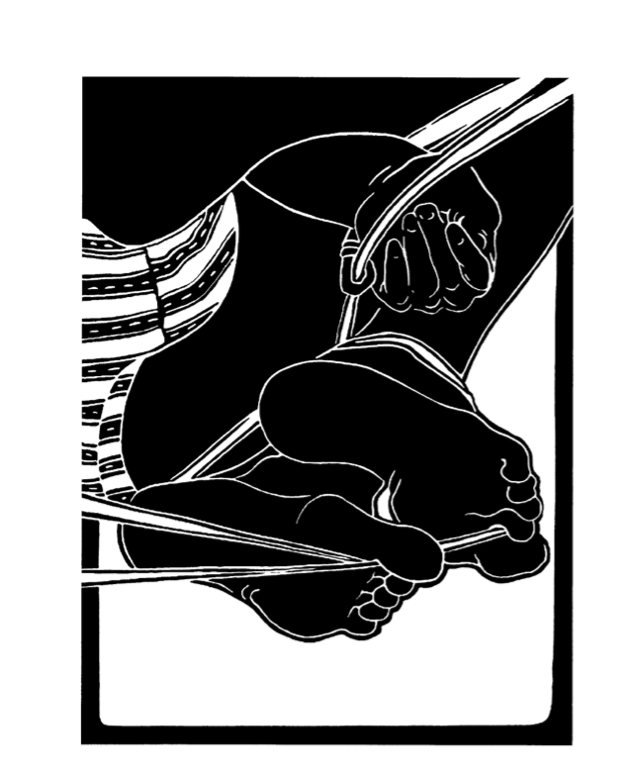

Sonia Gutiérrez, Cimitarra: vivo o muerto al aeropuerto, 1976 Courtesy of Sonia Gutiérrez

I can envision Isabel Ruiz (Guatemala, 1945–2019) doing her performance Matemática sustractiva (Subtractive math) on June 7, 2008, when she drew 45,000 lines with chalk, marking the number of dead and disappeared during the Guatemalan internal conflict (1960-96). Ruiz’s gestures may seem useless, even pointless, but in their beautiful absurdity, they offer solace, they become a hypnotic gesture of love. These works are not healing per se, nor they have a concrete purpose. But they speak out to injustice, they are a form of denunciation, of seeking justice, an act of remembrance for those lost, many of them anonymous, or only mourned by the close family circle, sometimes in secret.

I traveled to Guatemala few weeks after Stephanie’s tragedy, and during the trip we went with my friend, the Guatemalan art collector Hugo Quinto, to the Laguna de Chicabal to make an offering for her and my brother. This is a sacred lake to Mayan people and is in the crater to a volcano at an elevation of 2,712 meters. Hugo had caught Covid-19 during the first wave and had spent a month in intensive care, and climbing the volcano was a daunting prospect that meant facing the trauma of his past sickness. The climb for reaching the lake is steep, followed by a descent into the crater. We arrived quite late in the afternoon, and the lake was engulfed in mist.

Hugo Quinto, Untitled (Laguna de Chicabal), August 15, 2021 Courtesy of Hugo Quinto

It was an otherworldly experience of extreme beauty and stillness. We walked as if floating towards the lake to reveal that all around the inner edges inside the lake were beautiful floral arrangements of offerings to the deceased. Time here stops, it becomes the immemorial presence of the sacred. Our floral offering was placed next to the other ones in the lake, forever in the care and company of thousands of years of lives, rituals, culture and beauty. This too was the gift of art, and more.

Cecilia Fajardo-Hill, the 2021-22 DRCLAS Central American Visiting Scholar, is an independent British/ Venezuelan art historian and curator in modern and contemporary art, focusing on Latin American and Latinx art. Presently is co-curator of Xican-a.o.x. Body, 2023, and is working on a book on Decolonial Latin American and Latinx art history in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Related Articles

A Review of Cuban Privilege: the Making of Immigrant Inequality in America by Susan Eckstein

If anyone had any doubts that Cubans were treated exceptionally well by the United States immigration and welfare authorities, relative to other immigrant groups and even relative to …

A Review of Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle

James Loxton’s Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle makes very important, original contributions to the study of…

Endnote – Eyes on COVID-19

Endnote A Continuing SagaIt’s not over yet. Covid (we’ll drop the -19 going forward) is still causing deaths and serious illness in Latin America and the Caribbean, as elsewhere. One out of every four Covid deaths in the world has taken place in Latin America,...