The Legacy of War

From El Salvador to Boston

Miguel was six years old when he was forced to witness the execution of his first-grade teacher for participating in a teachers’ strike. “What I remember is that the guard turned around and pointed a G-3 to our heads and told us that if we went down that road, he would kill us too.” The image of the teacher falling on the school grounds haunts him to this day. The story of Miguel (not his real name) is one of several personal testimonies I heard during an investigation I carried out about survivors of El Salvador’s war in the 1980s then living in the Boston area. Their stories are a poignant attestation of human resilience.

I interviewed ex-guerrilla members, army veterans, torture survivors, civilians, and two Americans who regularly visited El Salvador during the war. As their stories slowly unfolded, I came to realize that many immigrants today still live in utter silence about the horrors experienced during the Cold War era. They manage to lead normal lives, some have been even professionally successful in the health care or non-profit sectors; most are U.S. citizens and have extended families, but their internalized traumas go largely unnoticed.

Take Cecilia, for example, who was eleven when she first saw a massacre during a student demonstration in 1975. After that, “I started witnessing difficult situations that I could not comprehend… When people began to disperse, you could see a suitcase here, a purse there, books, shoes… There was blood everywhere… On top of that… this feeling of insecurity or lack of trust, and not being able to talk about it.” Now in her 40s, Cecilia explained that that feeling never really went away. During stressful situations it creeps back in, leaving her exhausted, she told me.

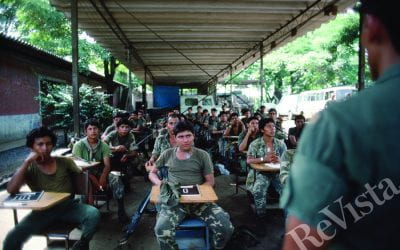

The United Nations Truth Commission in El Salvador determined that 85% of human rights violations were committed by state agents just in the period between 1980 and 1992. Yet social unrest in the 1960s and 1970s was also violently repressed in El Salvador, marked by mutilated bodies thrown by the side of the road and extrajudicial killings to instill terror in the population. Many of the stories I heard go back to that earlier period and are marked by a deep feeling of helplessness and distrust of law enforcement. “The army and the [national] guard are supposed to protect you, but what do you do when those who are supposed to protect you are killing you?” said Miguel as an explanation of how he joined the guerrilla. It became a matter of survival, you joined one side or the other.

One of the military members I interviewed, Carlos (not his real name), explained that as the eldest member of his family, he was approached by both the army and the guerrillas to join their ranks, but ended up in the army because otherwise his family could have been labeled as leftist sympathizers—a deadly target. He painfully described to me his participation as a member of a death squad, something he was not proud of. It left him emotionally detached from his present wife and children and suffering from PTSD. When I met him he was undergoing therapy, finally, after 20 years of silence.

Ana Milagros left El Salvador in 1978 and managed a smile when she told me she came to the United States undocumented and worked for every penny to bring her entire family here. “My mom, my sister, my brothers… I didn’t want them to be there. I wanted to erase all of that. To bury it all.” She lived some of the worst violence in San Salvador and prayed every day on her way to work that a stray bullet or a bomb wouldn’t end her life. “In the morning you go to work, and you don’t know if you’re coming back. You had to put your trust in God.”

“I never wanted to come here,” said César (not his real name), a union organizer who now works as a mechanic. He was tortured in a military barrack for almost two months and had to undergo seven years of physical therapy to fix four damaged vertebrae. “I knew very well how hard life is here for the immigrant; it’s not easy… But I stayed in the system because of my children, to give them a better future because in El Salvador, there is no future.”

The silence these people have lived in is what struck me the hardest. For most of those interviewed, I was the first person they had talked to about their experiences. The result was very cathartic and painful: a tearful release of the horrors lived, a mix of pride and shame. Pride for finally speaking out; shame for surviving, for the silence, for leaving loved ones behind.

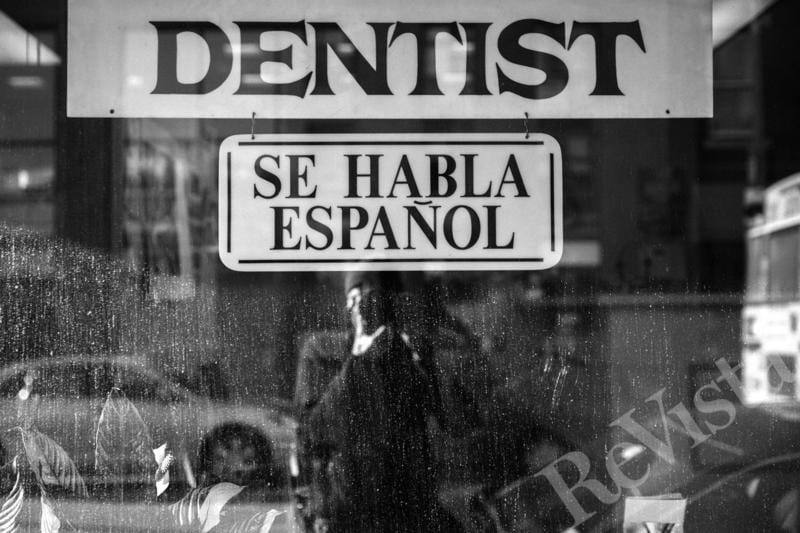

According to the Migration Policy Institute in 2013 there were around 38,200 Salvadorans living in Boston, out of more than 1.1 million who migrated to the United States. Their population increased 12-fold since 1980, 70-fold since 1970. Many of them have found economic success in towns like East Boston, Allston and Jamaica Plain, although the war and its consequences still haunt their communities. To listen to their stories, in their own words, visit: www.memoryandpeace.com.

Spring 2016, Volume XV, Number 3

Sofía Jarrín-Thomas is a radio freelance journalist with a focus on human rights, social movements, the environment, and immigration. Her print and audio work has been published in several independent outlets in the United States and Latin America, including Truthout.org, Ecoportal.net, Z Magazine, Bolpres.net, Pacifica Radio, Free Speech Radio News, ALER and AMARC.

Related Articles

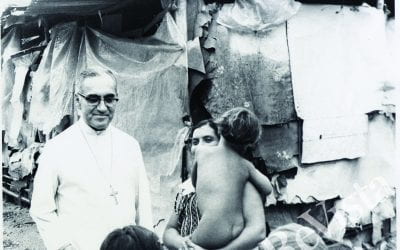

The Boy in the Photo

The mangy dogs strolled everywhere along the railroad track. I remembered dogs just like them from the long-ago day in La Chacra in 1979 with Archbishop Óscar Romero, just months before he was killed…

Beyond Polarization in 21st-century El Salvador

My father was a civil engineer who worked for the government during the civil war years. He specialized in roads and had to spend several days a month traveling to remote places in El Salvador. I was 10 in 1986, and I remember my mom asking my dad…

El Salvador: Editor’s Letter

I had forgotten how beautiful El Salvador is. The fragrance of ripening rose apples mixed with the tropical breeze. A mockingbird sang off in the distance. Flowers were everywhere: roses, orchids, sunflowers, bougainvillea and the creamy white izote flower…