The Migrant Architecture of El Salvador

Photos by Walterio Iraheta

In the summer of 2015 I traveled to the city of San Salvador to meet photographer Walterio Iraheta. After publishing my book on the remittance-funded landscape and architecture of Mexico, I wanted to learn about the changing rural landscape caused by El Salvador’s remittance boom, a subject Iraheta began photographing in his native country in 2006. Propelled north since the 1980s and 90s because of the civil war, today approximately two million Salvadorans—more than 25% of the country’s total population—live abroad. The exodus continues, now fueled by violence and lack of economic opportunity.

This migration to the United States is mirrored by a continuous flow of dollars south. By 2013, the 4.2 billon dollars streaming into El Salvador’s economy accounted for an astounding 16 percent of its GDP. Some migrants have built impressive new homes— what I call “remittance homes’”—with dollars earned in the United States, resulting in dramatic changes across rural landscapes.

Iraheta’s photographs allow me to compare the architecture of Mexico’s remittance homes to those found in El Salvador. The American flags etched in plaster on the façades of El Salvadoran homes and the miniature replicas of the Statue of Liberty found in Mexican ones both function as public announcements of distant horizons, and are intended to represent migrants’ gratitude toward the United States. Iraheta describes the homes as “autorretratos” or self-portraits; each home is a crystallization of the special desires and circumstances of a migrant family in the context of migration. While the photographs allow me to compare the homes visually, it was out in the field with Iraheta—when we went to document architectural changes to homes he had previously photographed—that the stakes of migration and remitting as a way to a better life for Salvadoran families were revealed.

On our first day out, Iraheta and I visited Ilobasco, a town about an hour east of San Salvador with 60,000 inhabitants. Iraheta had arranged for a municipal employee to be our formal guide through Ilobasco’s barrios. Upon arrival, we were told that unfortunately there was no official car available for our trip. But, after we suggested the use of our car or the local tuk tuk taxis, he explained that it was not safe to go and take pictures of migrant houses—no matter that they were abandoned. The gangs of Ilobasco have territorial sovereignty over the areas beyond the main plaza. These are the same places from which many migrants have fled, and where they subsequently built new homes financed by dollars. Around the plaza, where our conversation took place, the local government maintains order and commerce thrives, but beyond the central district, he explained, we would risk being beaten or shot simply because we would not be recognized—“they don’t wait to ask questions.” At that moment, frustrated by the promise of being so close to Ilobasco’s remittance homes, I imagined what this meant for families who had risked everything to build them. The transformation of the barrio due to the increasing prominence and power of local gangs robbed migrants of their dream home, whether built for residence, vacation or for retirement; as the neighborhoods became inaccessible, the houses remain empty—symbols of cultural and economic changes in the region.

Remittances homes are also symbols of migrant success and their continuing (and often increasing) importance in their country of origin. Achieving what would have been unattainable without migration, many of these aspirational homes are in what Iraheta calls “estilo hermano lejano” or far-away brother style. Hermano lejano, like Mexico’s colloquial terms norteño (northerner) and hijo ausente (absent son or daughter), encapsulates the sadness people experience on a daily basis in emigration villages and towns. Built for a brighter future, prominent homes dotting countryside’s become memorials—testimonies—to the men, women and children who remain far away.

Spring 2016, Volume XV, Number 3

Sarah Lynn Lopez, an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin, is an architectural and urban historian.

Walterio Iraheta is a Salvadoran photographer and curator.

Related Articles

The Salvadoran Right Since 2009

English + Español

In 2009, as the FMLN celebrated its long-awaited first foray into the Casa Presidencial, El Salvador’s largest conservative party—the Nationalist Republican Alliance (Alianza Republicana…

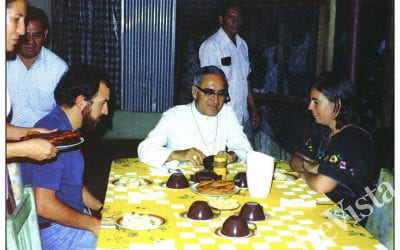

Remembering Romero

English + Español

As the meeting was ending, Romero—who hadn’t yet been installed — was asked if he’d like to say a few words. For all Schindler knew, they…

Indigenous Rights in El Salvador

English + Español

The story I will tell you here is of a remarkable woman, the last in a centuries-long line of Maya-Lenca matriarchs and a living conduit of ancient traditions brought into the modern world. It is…