The Nature of the Tropical Nature

Brazil Through the Eyes of William James

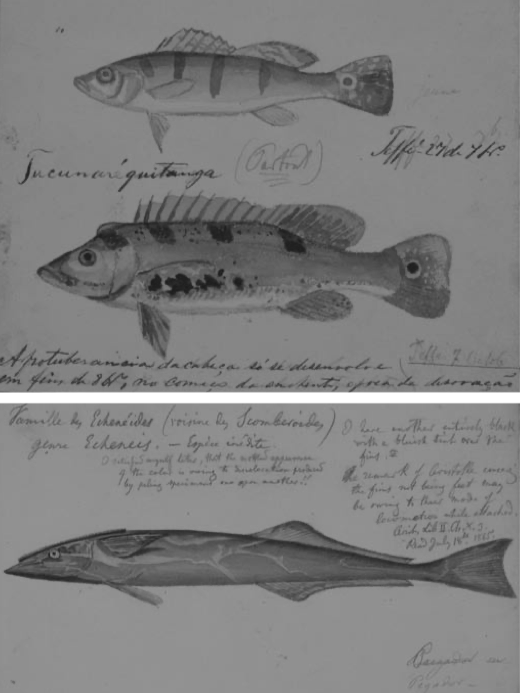

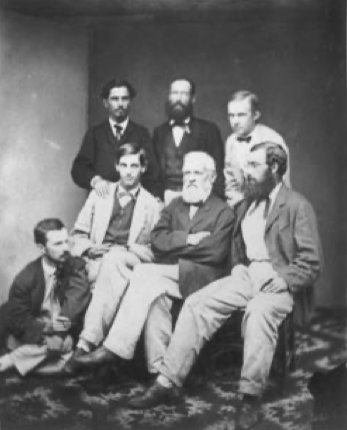

Above: William James, Louis Agassiz and other expedition members. Right: James took copious notes and illustrated them.

T statements that Brazil has been blessed in terms of nature. Indeed, from our earliest childhood, we learn to identify our country through enthusiastic manifestations about the wonders of our geography, not to mention the flora and fauna whose extraordinary diversity and wealth comprise the treasures that God generously bestowed upon us (of course, while all other nations have had to work hard to amass wealth). Even Pedro Vaz de Caminha’s inspired letter reporting the discovery of new lands to the King of Portugal in 1500, which described these lands in terms of Eden, seems to predict that our destiny was to be a part of nature. Nothing but nature.

Precociously announced in the early colonial period’s “visions of Eden,” this destiny became more fully established in 19th-century travel narratives, which recreated the discovery of new lands and reproduced the initial awe expressed by the early chroniclers in their descriptions of an earthly Paradise. In describing diverse species of monkeys, sloths, manatees, and other wonders of the animal kingdom (which in a sense included mention of naked savages), all allocated in an atemporal natural setting of tropical forests and rivers, 19th-century travel literature often identified Brazil in terms of its exotic flora and fauna, above and beyond any recognition of its social implications.

As a scholar interested in travel accounts written in this period, I find myself almost compelled to sympathize with the few luminous writers who in one way or another strayed away from the general tone, helping make our nature-prison less panoptic. For example, I cannot help identifying myself with a passage from the great Machado de Assis, novelist and social critic who in 1892 expressed his anguish with our often compliant objectification: “This adulation of nature has always caused pain to my nativistic heart, or whatever it might be called.” Continuing his weekly chronicle in the usual mordant, ironic tone, Machado displayed his discomfort with our reification as tropical nature, in describing a visit to the Castelo Hill in Rio de Janeiro, showing a foreign visitor a colonial church: “I am aware that these are not the ruins of Athens; but one can only show what he has. The visitor went in, took a quick look, came out and settled against the outer wall, gazing at the sea, the sky and the mountains. After about five minutes, he exclaimed: ‘What nature you have!’ … Our guest’s admiration excluded any idea whatsoever of human action. He didn’t ask me when the fortresses were built, or the names of the ships anchored in the harbor. Nothing but nature” (cited in Flora Sussekind, O Brasil não é longe daqui, p. 267).

And what does this have to do with William James’s journey to Brazil in 1865-66, as a member of the Thayer Expedition, which was led by Louis Agassiz, director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology and influential professor at Harvard’s Lawrence School? Well, from the moment I set eyes on James’ Brazilian papers, written when he was only 23 years old, I noticed something of an original spirit palpitating. In spite of being part of a naturalist’s journey, organized according to well-established patterns, James seemed to establish himself in a position of intellectual independence. His voice was different from those who only sought to produce a rationalizing, extractive, and dissociative understanding, suppressing functional and experiential relations between people, plants, and animals, consolidating a descriptive paradigm that appropriated an apparently benign and totally abstract world, producing a naive and utopian vision of male, European authority (cf. Mary Pratt, Imperial Eyes). Unlike what one would expect from someone involved as a volunteer in a scientific collecting expedition, James engaged in a different kind of intellectual journey during the eight months of his sojourn in Brazil, spent mostly in Rio de Janeiro and in the Amazon. He scribbled letters to his family, wrote a brief (incomplete) narrative describing his trip to the Solimões River, maintained a journal, and sketched a series of drawings depicting scenes and people from the expedition, which express not only a critical consciousness but also a moral distance from the colonialist intellectual enterprise that guided the expedition. Because of this, although James’s Brazilian writings are well known to all the scholars—including Ralph Barton Perry, Gerald Myers, Howard Feinstein, Kim Townsend, Louis Menand, Paul Jerome Croce, Daniel Bjork, and many others—who meticulously have studied this charismatic figure from the perspective of his intellectual biography and his place in the history of Harvard’s consolidation as a modern university, these papers have yet to receive attention within the wider context of nineteenth-century travel literature. They stand out in terms of the special empathy that James displays in his observations on the tropical environment and the nonwhite populations that inhabited it. Among Latin Americanists, only Nancy Stepan dedicated some attention to James’s papers in her recent book, Picturing Tropical Nature. Furthermore, I believe that an analysis informed by this perspective can offer a new fold to the well-known biography of the founder of Pragmatism.

Of course, James’s Brazilian writings are not always, shall we say, illuminated by an empathetic and relativistic approach. James expresses many feelings and emotions in his letters and journal, beginning with his ambivalence in relation to the significance of the journey itself. He narrated moments of boredom and restlessness, revealing his desire to go home as soon as possible or his irritation with the lethargy and inefficiency of the natives, as one might expect from a young man facing such a journey. The trip was not only strenuous, endeavoring to cover little known areas of South America, but it separated James for the first time from a very absorbing family, placing him under the orders of Agassiz, who was prone to erratic and tempestuous decisions, changing travel plans spuriously and keeping his subordinates always at his beck and call.

In addition, James caught what he believed to be smallpox during the first months of his stay in Rio de Janeiro, with potentially dire consequences that deepened his indisposition towards the journey for months. Agassiz, however, claimed that James suffered from a more benign illness. He continued his schedule of social and scientific visits to surrounding plantations, leaving his student to face a serious health risk that left the young man temporarily blind.

On some occasions, James simply succumbed to the exotic, as for example in his frequently cited letter to Henry James, dispatched from the “Original Seat of the Garden of Eden,” in which he employs images derived from a standard repertory of descriptions of tropical nature. “No words but only the savage inarticulate cries can express the gorgeous loveliness of the walk I have been taking”, he wrote. “Houp la la! The bewildering profusion & confusion of the vegetation, the inexhaustible variety of its forms & tints (yet they tell us we are in the winter when much of its brilliancy is lost) are literally such as you have never dreamt of. The brilliancy of the sky & the clouds, the effect of the atmosphere wh. gives their proportional distance to the diverse planes of the landscape make you admire the old Gal nature.” Later in the same letter, James appeals decidedly to the exotic, characterizing his surroundings as “inextricable forests” and referring to the local inhabitants as a naturalized component of the landscape: “On my left up the hill there rises the wonderful, inextricable, impenetrable forest, on my right the hill plunges down into a carpet of vegetation wh. reaches to the hills beyond, wh. rise further back into the mountains. Down in the valley I see 3 or four thatched mud hovels of negroes, embosomed in their vivid patches of banana trees.” These hyperbolic exclamations invite the reader to imagine a pristine, mysterious, and especially impenetrable landscape, quite consistent with conventional notions in the Northern Hemisphere regarding tropical nature.

This is how many of James’s biographers imagined the journey, citing and analyzing this letter as an illustration of the kind of intellectual and emotional experience evoked by the lush and liberating world of tropical forests. Although James did not specify the exact location of this excursion, clearly it took place in the Tijuca Forest, only a few miles (not 20, as James supposed, but around 8, as established by the Agassiz couple in their Journey in Brazil) from the urban center of Rio de Janeiro, a pleasant location frequented by the upper crust of Rio’s society on weekends for strolls and picnics. On that occasion, Agassiz’s party stayed overnight at the Bennett Hotel, belonging to an Englishman and boasting modern amenities. Tijuca, of course, was and still is lovely, in spite of the high-class residential neighborhoods and shopping malls that occupy the region. However, it hardly represented a tropical jungle experience, as James in fact was to experience in later months in the Amazon. From the vantage point of mid-19th century Rio de Janeiro, an excursion to the Tijuca Forest was little more than a polite social outing, not unlike an excursion that contemporary Bostonians or Cantabridgians might make to the shores of Walden Pond on a summer day!

James can be surprising, though. One expects him to be conventional, with salutes to the exotic character of the natives and odes to a mysterious, atemporal, and asocial Nature, as a traveler who seeks to establish a secure emotional distance from his experience, fearing the risks of liberating the unconscious. But James takes risks and not only is he particularly perceptive in his demolition of the tropical nature myth, but also he is capable of empathizing with that which he describes, including the native populations. He invites his readers to discover that Rio de Janeiro had a European air to it (“The streets in town & shops remind you so much of Europe”, in a letter dated April 21, 1865), that the Amazon was relatively civilized (“This expedition has been far less adventurous & far more picturesque than I expected. I have not yet seen a single snake wild here…” letter, Oct. 21, 1865), and finally that the tropical environment was not all that mysterious, but rather somewhat tedious and repetitive (“here all is monotonous, in life and in nature that you are rocked into a kind of sleep…”, Dec. 9, 1865).

James is at his best when he shows that he is capable of empathizing with the local inhabitants, guides, fishermen, and others, the Indians, Blacks, and mestizoes who accompanied the collecting excursions, often as his only companions. In one of my favorite passages, James, obviously greatly inspired on that day, observed a conversation between his boatmen and a group of Indian women who conducted a canoes downstream on the Solimões River: “I marvelled, as I always do, at the quiet urbane polite tone of the conversation between my friends and the old lady. Is it race or is it circumstance that makes these people so refined and well bred? No gentleman of Europe has better manners and yet these are peasants” (William James Diary, 1865-66, Houghton Archives). This and other luminous passages written in a disinterested tone show how the young James dealt with the problematical concept of race informally by turning it on its head, showing signs of the charismatic and brilliant teacher that was to exert a special attraction over those who came to know him. In confronting the conventional, stereotyped repertory of tropical travel narratives, James exercised his peculiar skill of empathizing with the world that surrounded him, relativizing cultural codes in their own terms. For someone like James, who had begun the trip with a terrible seasickness and who soon discovered “[i]f there is any thing I hate it is collecting” (letter dated Oct. 21, 1865), the journey to Brazil ended up being quite productive.

Revealing an unconventional and empathetic traveler, James’s Brazilian papers have yet to be subjected to a theoretical inquiry that is more appropriate to the kind of experience he lived and the kind of account he produced. It is in this spirit that I am preparing a critical edition of this material. After all, amidst the suffering and deprivation that a tropical journey could cause in the mid-1860s, we find a distinctive approach in the first discovery of the other, the other who James, not without some effort, pleasantly came to appreciate.

A Natureza da Natureza Tropical

O Brasil pelos Olhos de William James

por M.H. Machado

A nós, brasileiros, nenhuma declaração pode soar mais óbvia do que aquela que nos assegura que o Brasil é um país privilegiado em termos da natureza, que suas praias são lindas, que suas florestas tropicais encantadoras, que seus rios majestáticos, suas paisagens magníficas. Desde a mais tenra infância somos treinados a identificar nosso país por meio de exclamações entusiásticas sobre as maravilhas da nossa geografia, isto sem falar da flora e da fauna, cuja variedade e riqueza são, nada mais nada menos, do que tesouros que ganhamos gratuitamente de Deus (isto, claro, quando todos os outros povos estão por ai trabalhando para amealhar as próprias riquezas). A própria carta inspirada de Pero Vaz de Caminha – o primeiro cronista a dar notícias ao Rei de Portugal do achamento das terras novas mais tarde denominadas de brasis – e que se deleitou em descrevê-las em traços edênicos, nelas sublinhando especialmente a presença de inocentes adões e evas nús e amigáveis, ao brindar a nova terra com uma peça de boa literatura e muito encantamento, parecia estar nos destinando a sermos natureza. E só natureza.

Este destino precocemente anunciado nas “visões do paraíso” dos primeiros séculos veio a se confirmar plenamente na literatura de viagem do século XIX. De fato, os relatos de viagem do XIX, ora sublinhando a la Humboldt os aspectos românticos idealistas da paisagem americana, ora voltando-se para o empreendimento científico-classificatório dos naturalistas, a la Martius ou Agassiz no Brasil, ora ainda explorando o pitoresco das descrições dos costumes e relações sociais dos nativos, como o fizeram uns tantos viajantes-aventureiros-comerciantes, se dedicaram a reencenar a descoberta das novas terras, reinventando o espanto original dos velhos cronistas frente à visão do suposto paraíso terreal. Assim, se desde o início já havíamos sido fadados ao mundo natural, o século XIX realizou o mais plenamente possível o nosso destino anunciado. Descritos pelos nossos macacos-mãos-de-ouro, mico-saguis, bichos-preguiça, peixes-boi e outras maravilhas do mundo animal, na qual não faltavam o selvagem despido, todos alocados na natureza atemporalizada de florestas e rios tropicais, o Brasil da época aparecia nesta literatura definitivamente classificado fora do mundo social. De forma que como estudiosa dos relatos de viagem escritos sobre o Brasil do século XIX sou quase compelida a me solidarizar com todos aqueles – por sinal, poucos e raros escritores iluminados– que, de uma maneira ou de outra, discordaram do tom geral, ajudando a tornar nossa prisão-natureza menos panóptica. Não posso deixar de me solidarizar, por exemplo, com uma passagem do grande Machado de Assis, escritor de romances realistas e crítico dos nossos costumes sociais que, em 1893, expressava sua angústia frente à coisificação da qual éramos objetos um tanto quanto voluntários, declarando: “O meu coração nativista, ou como quer que lhe chamem, sempre se doeu desta adoração da natureza.” E continuava ele sua crônica semanal, no costumeiro tom mordaz e contido, o qual deixava entrever seu desgosto quanto a nossa reificação enquanto natureza tropical, relatando a visita que fizera ao Morro do Castelo, na cidade do Rio de Janeiro, com objetivo de mostrar a um visitante estrangeiro os altares da igreja local: “Sei que não são ruinas de Atenas; mas cada um mostra o que possui. O viajante entrou, deu uma volta, saiu e foi postar-se junto à muralha, fitando o mar, o céu e as montanhas, e, ao cabo de cinco minutos: “Que natureza que vocês têm!”… A admiração de nosso hóspede excuíia qualquer idéia de ação humana. Não me perguntou pela fundação das fortalezas, nem pelo nome dos navios ancorados. Foi só a natureza”.

E o que tem isso a ver com a viagem que William James fez ao Brasil entre 1865-66, acompanhando a Expedição Thayer, liderada pelo então diretor do Museum of Comparative Zoology e professor dileto da Lawrence School da Harvard, o notável Louis Agassiz? Bem, desde a primeira vez que passei os olhos pelos papés escritos no Brasil por James, então um jovem de apenas 23 anos de idade, senti que ali palpitava um espírito original, alguém que, apesar de estar inserido numa viagem naturalista, organizada segundo os padrões já bem analisados – isto é, como produtora de entendimento racionalizador, extrativo e dissociativo, que suprimia as relações funcionais e experenciais entre as pessoas, plantas e animais, consolidando um paradigma descritivo e uma apropriação do planeta aparentemente benigna e totalmente abstrata, produzindo uma visão utópica e inocente da autoridade mundial européia e masculina. (Mary Pratt, Imperial Eyes) – se colocava numa posição de independência intelectual. Contrariamente do que se espera de alguém que se engajara numa expedição de coleta de peixes e materiais geológicos na condição de assistente e coletor voluntário, James, em seus oito meses de estadia no Brasil, passadas principalmente no Rio de Janeiro e na Amazônia, garatujou cartas enderçadas a seus familiares, redigiu uma curta narrativa de viagem ao Rio Solimões (esta incompleta), rascunhou um diário e produziu desenhos de qualidade desigual de cenas e figuras da expedição, que expressam uma consciência crítica e um distanciamento moral do empreendimento intelectual colonialista que norteava a expedição. E é por isso que, embora muito bem conhecidos por todos os estudiosos da figura carismática de William James, que já os esmiuçaram amplamente, sempre do ponto de vista da formação intelectual de James, de sua geração e da formação da Harvard University – como Ralph Barton Perry, Gerald Myers, Howard Feinstein, Kim Towsend, Louis Menand, Paul Jermoe Croce, Daniel Bjork entre muitos outros – os registros brasileiros de James ainda merecem um tratamento que os insira no quadro da literatura de viagem naturalista do XIX, distinguindo-os por sua especial empatia na análise do ambiente tropical e das populações não-brancas que o habitavam. Além disso, acredito que uma análise informada por esta perspectivas pode oferecer novas vertentes da própria biografia do fundador do Pragmatismo.

Claro, que os papéis brasileiros de James não são sempre, digamos assim, iluminados por uma aproximação empática e relativista. Neles James expressou muitos sentimentos e emoções, como sua ambivalência com relação ao próprio sentido da viagem, narrou seus momentos de tédio e dúvida, sua vontade de ir o mais rápido possível para casa, seu mal humor com relação a morosidade e preguiça dos nativos, tal como se poderia esperar de um jovem que, engajando-se numa viagem de tal envergadura, que pretendia percorrer áreas poucos conhecidas da América do Sul, se separa, pela primeira vez, de uma família absorvente, colocando-se sob os desígnios de um Agassiz, capaz de decisões erráticas e intempestivas, e que, além do mais, mudava o roteiro da viagem ao sabor dos acontecimentos, matendo seus dependentes sempre na expectativa de suas ordens. Arescente-se a isso o episódio da chickenpox sofrida por James, logo nos seus primeiros meses de estadia no Rio de Janeiro e cujas consequências poderiam ter sido ainda mais funestas e que o indispôs , compreensivelmente, por mêses, contra a viagem e tudo que a cercava. (Por sinal, lendo os registros do episódio da doença de James, acredito que ele realmente tenha tido catapora e não, como supôs Agassiz, varicela, que é um tipo de doença mais benigno). O fato de que James tenha recebido tão pouca atenção dos Agassiz, que não deixaram de visitar fazendas em paragens distantes e quase inacessíveis enquanto um de seus estudantes passava por riscos de vida consideráveis, pode explicar o motivo deste julgamento. Em outros momentos, James simplesmente sucumbiu à exotização, como, por exemplo, na sua muito citada carta a Henry James, endereçada do “Original Seat of Garden of Eden” (July 15th 1865. Houghton Archives), e na qual ele lança mão de imagens derivadas de todo um repertório padrão de descrição da natureza tropical. Segundo ele, por exemplo, apenas “savage inarticulate cries” poderiam expressar as maravilhas do landscape, recoberto de “bewildering profusion & confusion of the vegetation”, and “the inexhaustible variety of its forms & tints”. Estas e outras exclamações hiperbólicas utilizada por James convidam o leitor a imaginar um landscape selvagem e misterioso, bem em consonância com o que, no hemisfério norte, se convencionou caracterizar o ambiente dos trópicos. E assim o fizeram os biógrafos de James, que amplamente citaram e analisaram esta missiva como representativa de um tipo de experiência, intelectual e emocional, evocada pelo mundo luxuriante e liberador das selvas tropicais. Embora o próprio James não tenha localizado o local exato da excursão, é fácil determinar que esta havia se dado na Tijuca, paragem distante apenas algumas milhas da cidade do Rio de Janeiro (não 20 milhas, como supôs James, mas 8, como determinou acertadamente os Agassiz) local aprazível, no qual as altas classes do Rio de Jameiro costumavam dirigir-se nos finais de semana para fazer pequenas excursões de recreio e picnics. Além disso, a excursão liderada por Agassiz, pernoitou no local, hospedando-se no Hotel Bennet, de propriedade de um inglês, que possuía instalações bastante modernas e aprazíveis. Não que a Tijuca não seja linda, é esta ainda hoje, apesar dos condomínios de luxo e shopping malls que hoje povoam este bairro de classe média do Rio de Janeiro, um local de extraordinária beleza. No entanto, muito longe estava a Tijuca de proporcionar uma experiência de selva tropical, como, de fato, James teria em sua estadia nos mêses seguintes na Amazônia. Do ponto de vista dos cariocas a excursão à Tijuca não passava de um passeio bem educado de final de semana, similar a uma excursão que faziam os bostonians to the shores of Walden Pond nos dias de verão!

No entanto, quando se espera que James seja convencional e que repita o que dele se espera, isto é loas ao exotismo dos nativos e odes a uma natureza misteriosa, atemporal e associal, na qual o viajante presentindo os riscos de uma experiência interna de liberação insonsciente, estabelece um seguro distanciamento emocional do ambiente, ele arrisca e se mostra tanto particularmente persipcaz na demolição do mito da natureza tropical quanto capaz de empatizar com o que vê, sobretudo com as populações nativas. E não mais que de repente somos convidados a descobrir que o Rio de Janeiro é uma cidade que relembra Paris Letter *), que a Amazônia é relativamente civilizada (*), que o ambiente tropical, ao fim e ao cabo, não é assim tão misterioso, mas sim as vezes meio tedioso e repetitivo (*). James se excede, sobretudo, quando quando se mostra capaz de empatizar com os moradores locais, guias, pescadores e outros, índios, negors e mestiços que acompanharam suas excursões de coleta, muitas vezes como suas únicas companhias. Em uma de minhas passagens prediletas, James, obviamente em dia de grande inspiração, observando a conversação dos seus barqueiros com um grupo de mulheres indígenas ou mestiças que pilotavam uma montaria rio abaixo, em algum ponto do Rio Solimões, se pergunta: I marvelled, as I always do, at the quiet urbane polite tone of the conversation between my friends and the old lady. Is it race or is it circumstance that makes these

people so refined and well bred? No gentleman of Europe has better manners and yet these are peasants. (William James Diary 1865-1866, A.Ms.s., 1865, 4498, Houghton Archives). Estas e outras passagens iluminadas que ficaram gravadas em páginas redigidas em tom familiar e descompromissado mostram o jovem James enfrentando, de maneira informal, o famigerado conceito de raça e ainda assim invertendo-o, dando mostras da gestação do pensador carismático e professor brilhante que viria a exercer particular atração sobre todos que dele se aproximavam. Confrontando o convencional e o estereotipado do repertório da literatura de viagem aos trópicos, James experimentava sua peculiar habilidade de empatizar com o mundo que o cercava, relativizando os códigos culturais enquanto tais. Para quem, como James, havia começado a viagem sofrendo de um terrível seasickness e que logo descobriria que “If there is any thing I hate it is collecting” (Letter to To Henry James, Sr., and Mary Robertson Walsh James, ALS: MH bms AM 1092.9 – 2517, Houghton Archives), a viagem ao Brasil acabou sendo bastante produtiva. Mostrando um viajante anti-convencional e empático, os papéis brasileiros de James ainda estão por merecer uma moldura teórica mais adequada ao tipo de experiência que ele viveu e de relato a partir dai produzido. Afinal de contas, por entre as dores e privações de uma viagem aos trópicos nos anos de 1860, residem nos papéis de James os traços de uma primeira descoberta do outro, a quem James, não sem esforço, amigavelmente apreciou.

Fall 2004/Winter 2005, Volume III, Number 1

Maria Helena Machado is a Professor of Latin American History, University of São Paulo. A 2003-2004 DRCLAS Visiting Scholar, she is currently preparing a critical edition of James’ Brazilian papers.

John Monteiro, 2003-2004 Visiting Professor in Harvard’s Department of History, translated this article from Portuguese.

Maria Helena Machado é professora titular de História da América Latina pela Universidade de São Paulo. A 2003-2004 DRCLAS Visiting Scholar, ela está atualmente preparando uma edição crítica dos artigos brasileiros de James.

John Monteiro, 2003-2004 Professor Visitante no Departamento de História de Harvard, traduziu este artigo do português.

Related Articles

The Natural World

In the late spring of 1934, towards the end of my sophomore year at Harvard College, I received a letter from Dr. Frank E. Lutz, Entomology Curator at the American Museum of Natural History in…

Disappeared: A Journalist Silenced

The cover of Disappeared: A Journalist Silenced depicts the Guatemalan journalist Irma Flaquer holding up a page in her left hand as if proofreading. Yet, her eyes are not looking at the paper…

Kenneth Maxwell at DRCLAS

As the new coordinator of Brazilian Studies at the David Rockefeller Center, it is a treat for me to write a few words on Kenneth Maxwell’s arrival to DRCLAS, where he is now a Senior Fellow. To…